Related Research Articles

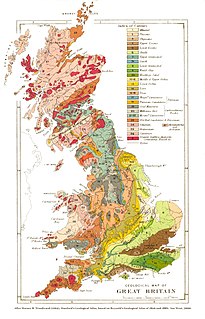

The geology of Great Britain is renowned for its diversity. As a result of its eventful geological history, Great Britain shows a rich variety of landscapes across the constituent countries of England, Wales and Scotland. Rocks of almost all geological ages are represented at outcrop, from the Archaean onwards.

The Howgill Fells are hills in Northern England between the Lake District and the Yorkshire Dales, lying roughly in between the vertices of a triangle made by the towns of Sedbergh, Kirkby Stephen and Tebay. The name Howgill derives from the Old Norse word haugr meaning a hill or barrow, plus gil meaning a narrow valley.

The geology of England is mainly sedimentary. The youngest rocks are in the south east around London, progressing in age in a north westerly direction. The Tees-Exe line marks the division between younger, softer and low-lying rocks in the south east and the generally older and harder rocks of the north and west which give rise to higher relief in those regions. The geology of England is recognisable in the landscape of its counties, the building materials of its towns and its regional extractive industries.

The geology of Wales is complex and varied; its study has been of considerable historical significance in the development of geology as a science. All geological periods from the Cryogenian to the Jurassic are represented at outcrop, whilst younger sedimentary rocks occur beneath the seas immediately off the Welsh coast. The effects of two mountain-building episodes have left their mark in the faulting and folding of much of the Palaeozoic rock sequence. Superficial deposits and landforms created during the present Quaternary period by water and ice are also plentiful and contribute to a remarkably diverse landscape of mountains, hills and coastal plains.

The London Basin is an elongated, roughly triangular sedimentary basin approximately 250 kilometres (160 mi) long which underlies London and a large area of south east England, south eastern East Anglia and the adjacent North Sea. The basin formed as a result of compressional tectonics related to the Alpine orogeny during the Palaeogene period and was mainly active between 40 and 60 million years ago.

The geology of East Sussex is defined by the Weald–Artois anticline, a 60 kilometres (37 mi) wide and 100 kilometres (62 mi) long fold within which caused the arching up of the chalk into a broad dome within the middle Miocene, which has subsequently been eroded to reveal a lower Cretaceous to Upper Jurassic stratigraphy. East Sussex is best known geologically for the identification of the first dinosaur by Gideon Mantell, near Cuckfield, to the famous hoax of the Piltdown man near Uckfield.

The geology of Suffolk in eastern England largely consists of a rolling chalk plain overlain in the east by Neogene clays, sands and gravels and isolated areas of Palaeocene sands. A variety of superficial deposits originating in the last couple of million years overlie this 'solid geology'.

The geology of Cambridgeshire in eastern England largely consists of unconsolidated Quaternary sediments such as marine and estuarine alluvium and peat overlying deeply buried Jurassic and Cretaceous age sedimentary rocks.

The geology of Essex in southeast England largely consists of Cenozoic marine sediments from the Palaeogene and Neogene periods overlain by a suite of superficial deposits of Quaternary age.

The geology of Kent in southeast England largely consists of a succession of northward dipping late Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks overlain by a suite of unconsolidated deposits of more recent origin.

The geology of Rutland in eastern England largely consists of sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age which dip gently eastwards.

The geology of Lincolnshire in eastern England largely consists of an easterly dipping succession of Mesozoic age sedimentary rocks, obscured across large parts of the county by unconsolidated deposits dating from the last few hundred thousand years of the present Quaternary Period.

The geology of Merseyside in northwest England largely consists of a faulted sequence of Carboniferous Coal Measures rocks overlain in the west by younger Triassic and Permian age sandstones and mudstones. Glaciation during the present Quaternary Period has left widespread glacial till as well as erosional landforms. Other post-glacial superficial deposits such as river and estuarine alluvium, peat and blown sand are abundant.

The Coralline Crag Formation is a geological formation in England. The Coralline Crag Formation is a series of marine deposits found near the North Sea coast of Suffolk and characterised by bryozoan and mollusc debris. The deposit, whose onshore occurrence is mainly restricted to the area around Aldeburgh and Orford, is a series of bioclastic calcarenites and silty sands with shell debris, deposited during a short-lived warm period at the start of the Pliocene Epoch of the Neogene Period. Small areas of the rock formation are found in locations such as Boyton and Tattingstone to the south of Orford as well as offshore at Sizewell.

The geology of West Sussex in southeast England comprises a succession of sedimentary rocks of Cretaceous age overlain in the south by sediments of Palaeogene age. The sequence of strata from both periods consists of a variety of sandstones, mudstones, siltstones and limestones. These sediments were deposited within the Hampshire and Weald basins. Erosion subsequent to large scale but gentle folding associated with the Alpine Orogeny has resulted in the present outcrop pattern across the county, dominated by the north facing chalk scarp of the South Downs. The bedrock is overlain by a suite of Quaternary deposits of varied origin. Parts of both the bedrock and these superficial deposits have been worked for a variety of minerals for use in construction, industry and agriculture.

This article describes the geology of the Broads, an area of East Anglia in eastern England characterised by rivers, marshes and shallow lakes (‘broads’). The Broads is designated as a protected landscape with ‘status equivalent to a national park’.

The geology of national parks in Britain strongly influences the landscape character of each of the fifteen such areas which have been designated. There are ten national parks in England, three in Wales and two in Scotland. Ten of these were established in England and Wales in the 1950s under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. With one exception, all of these first ten, together with the two Scottish parks were centred on upland or coastal areas formed from Palaeozoic rocks. The exception is the North York Moors National Park which is formed from sedimentary rocks of Jurassic age.

The geology of Exmoor National Park in south-west England contributes significantly to the character of a landscape which was designated as a national park in 1954. The bedrock of the area consists almost wholly of a suite of sedimentary rocks deposited during the Devonian, a period named for the English county of Devon in which the western half of the park sits. The eastern part lies within Somerset and it is within this part of the park that limited outcrops of Triassic and Jurassic age rocks are to be found.

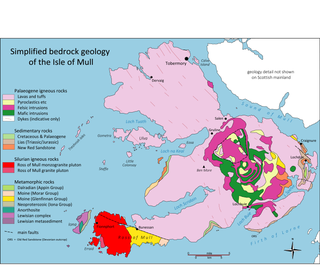

The geology of the Isle of Mull in Scotland is dominated by the development during the early Palaeogene period of a ‘volcanic central complex’ associated with the opening of the Atlantic Ocean. The bedrock of the larger part of the island is formed by basalt lava flows ascribed to the Mull Lava Group erupted onto a succession of Mesozoic sedimentary rocks during the Palaeocene epoch. Precambrian and Palaeozoic rocks occur at the island's margins. A number of distinct deposits and features such as raised beaches were formed during the Quaternary period.

The geology of the Gower Peninsula in South Wales is central to its character and to its appeal to visitors. The peninsula is formed almost entirely from a faulted and folded sequence of Carboniferous rocks though both the earlier Old Red Sandstone and later New Red Sandstone are also present. Gower lay on the southern margin of the last ice sheet and has been a focus of interest for researchers and students in that respect too. Cave development and the use of some for early human occupation is a further significant aspect of the peninsula's scientific and cultural interest.

References

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:625,000 scale geological map Bedrock Geology UK South 5th Edn. NERC 2007

- ↑ Brenchley, P.J. & Rawson, P.F. (eds) 2006 The Geology of England and Wales. The Geological Society, London. p142

- ↑ Brenchley, P.J. & Rawson, P.F. (eds) 2006 The Geology of England and Wales. The Geological Society, London. p442

- ↑ British Geological Survey 1:625,000 scale geological map Quaternary Map of the United Kingdom South 1st Edn. 1977