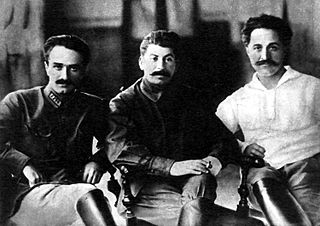

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin was a Soviet politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1922 to 1952 and as Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1941 until his death. Initially governing as part of a collective leadership, Stalin consolidated power to become a dictator by the 1930s. He codified his Leninist interpretation of Marxism as Marxism–Leninism, while the totalitarian political system he established became known as Stalinism.

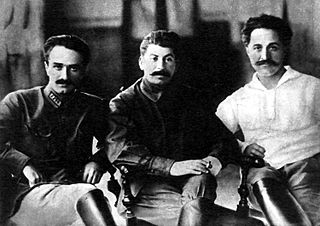

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph Stalin's secret police chiefs, serving as head of the People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) from 1938 to 1946, during the country's involvement in the Second World War. Beria was also a prolific sexual predator, who serially raped scores of girls and young women, and murdered some of his victims.

Nadezhda Sergeyevna Alliluyeva was the second wife of Joseph Stalin. She was born in Baku to a friend of Stalin, a fellow revolutionary, and was raised in Saint Petersburg. Having known Stalin from a young age, she married him when she was 17, and they had two children. Alliluyeva worked as a secretary for Bolshevik leaders, including Vladimir Lenin and Stalin, before enrolling at the Industrial Academy in Moscow to study synthetic fibres and become an engineer. She had health issues, which had an adverse impact on her relationship with Stalin. She also suspected he was unfaithful, which led to frequent arguments with him. On several occasions, Alliluyeva reportedly contemplated leaving Stalin, and after an argument, she fatally shot herself early in the morning of 9 November 1932.

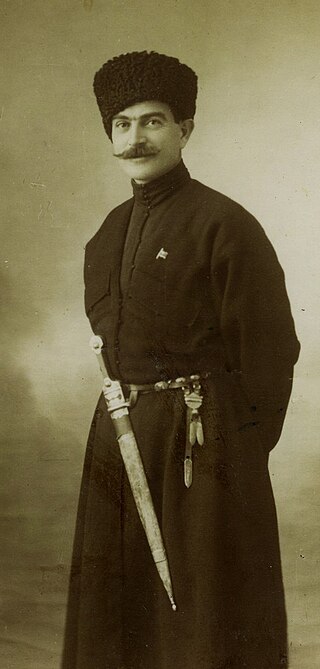

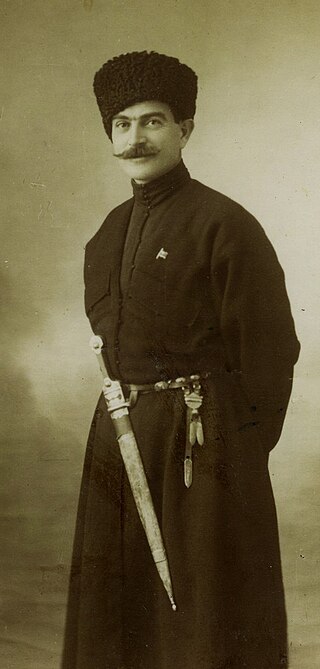

Kaikhosro "Kakutsa" Cholokashvili was a Georgian military officer and a commander of an anti-Soviet guerrilla movement in Georgia. He is regarded as a national hero in Georgia.

Ekaterine "Kato" Svanidze was the first wife of Joseph Stalin and the mother of his eldest son, Yakov Dzhugashvili.

Sergo Konstantinovich Ordzhonikidze was a Georgian-born Bolshevik and Soviet politician.

Yakov Iosifovich Dzhugashvili was the eldest son of Joseph Stalin, and the only child of Stalin's first wife, Kato Svanidze, who died nine months after his birth. His father, then a young revolutionary in his mid-20s, left the child to be raised by his late wife's family. In 1921, when Dzhugashvili had reached the age of fourteen, he was brought to Moscow, where his father had become a leading figure in the Bolshevik government, eventually becoming head of the Soviet Union. Disregarded by Stalin, Dzhugashvili was a shy, quiet child who appeared unhappy and attempted suicide several times as a youth. Married twice, Dzhugashvili had three children, two of whom reached adulthood.

Freedom Square or Liberty Square is located in the center of Tbilisi, Georgia, at the eastern end of Rustaveli Avenue.

Nestor Apollonovich Lakoba was an Abkhaz communist leader. Lakoba helped establish Bolshevik power in Abkhazia in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution, and served as the head of Abkhazia after its conquest by the Bolshevik Red Army in 1921. While in power, Lakoba saw that Abkhazia was initially given autonomy within the USSR as the Socialist Soviet Republic of Abkhazia. Though nominally a part of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic with a special status of "union republic," the Abkhaz SSR was effectively a separate republic, made possible by Lakoba's close relationship with Joseph Stalin. Lakoba successfully opposed the extension of collectivization of Abkhazia, though in return Lakoba was forced to accept a downgrade of Abkhazia's status to that of an autonomous republic within the Georgian SSR.

Mamia Orakhelashvili was a Georgian Bolshevik and Soviet politician energetically involved in the revolutionary movement in Russia and Georgia.

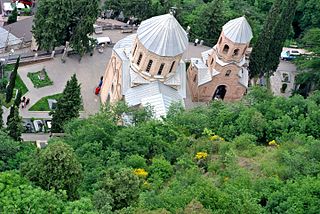

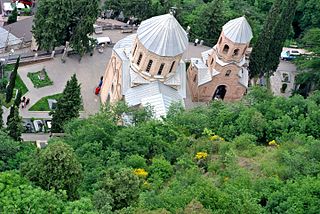

The Mtatsminda Pantheon of Writers and Public Figures is a necropolis in Tbilisi, Georgia, where some of the most prominent writers, artists, scholars, and national heroes of Georgia are buried. It is located in the churchyard around St David's Church "Mamadaviti" on the slope of Mount Mtatsminda and was officially established in 1929. Atop the mountain is Mtatsminda Park, an amusement park owned by the municipality of Tbilisi.

The Georgian affair of 1922 was a political conflict within the Soviet leadership about the way in which social and political transformation was to be achieved in the Georgian SSR. The dispute over Georgia, which arose shortly after the forcible Sovietization of the country and peaked in the latter part of 1922, involved local Georgian Bolshevik leaders, led by Filipp Makharadze and Budu Mdivani, on one hand, and their de facto superiors from the Russian SFSR, particularly Joseph Stalin and Grigol Ordzhonikidze, on the other hand. The content of this dispute was complex, involving the Georgians' desire to preserve autonomy from Moscow and the differing interpretations of Bolshevik nationality policies, and especially those specific to Georgia. One of the main points at issue was Moscow's decision to amalgamate Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan into Transcaucasian SFSR, a move that was staunchly opposed by the Georgian leaders who urged for their republic a full-member status within the Soviet Union.

Ioseb Iremashvili was a Georgian politician and author. A boyhood friend, and later political adversary, of Joseph Stalin, he is primarily known for his book Stalin und die Tragödie Georgiens, the first memoir of Stalin's childhood.

The Mingrelian affair, or Mingrelian case, was a series of criminal cases fabricated in 1951 and 1952 in order to accuse several members of the Georgian SSR Communist Party of Mingrelian extraction of secession and collaboration with the Western powers.

Sergey or Sergo Kavtaradze was a Soviet politician and diplomat who briefly served as head of government in the Georgian SSR and as Deputy Prosecutor General of the Soviet Union. A Georgian Bolshevik activist, he was persecuted for his Trotskyist activities, but was pardoned and reinstated by his personal friend Joseph Stalin.

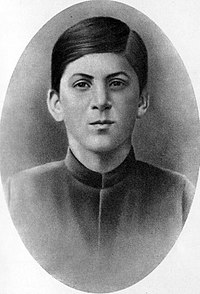

The early life of Joseph Stalin covers the period from Stalin's birth, on 18 December 1878, until the October Revolution on 7 November 1917. Born "Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili" in Gori, Georgia, to a cobbler and a house cleaner, he grew up in the city and attended school there before moving to Tiflis to join the Tiflis Seminary. While a student at the seminary he embraced Marxism and became an avid follower of Vladimir Lenin, and left the seminary to become a revolutionary. After being marked by Russian secret police for his activities, he became a full-time revolutionary and was involved in a various criminal activities as a robber, gangster and arsonist. He became one of the Bolsheviks' chief operatives in the Caucasus, organizing paramilitaries, spreading propaganda, raising money through bank robberies, and kidnappings and extortion. Stalin was captured and exiled to Siberia numerous times, but often escaped. He became one of Lenin's closest associates, which helped him rise to the heights of power after the Russian Revolution. In 1913 Stalin was exiled to Siberia for the final time, and remained in exile until the February Revolution of 1917 led to the overthrow of the Russian Empire.

Besarion Ivanes dze Jughashvili was the father of Joseph Stalin. Born into a peasant family of serfs in Didi Lilo in Georgia, he moved to Tbilisi at a young age to be a shoemaker, working in a factory. He was invited to set up his own shop in Gori, where he met and married Ekaterine Geladze, with whom he had three sons; only the youngest, Ioseb, lived. Once known as a "clever and proud" man, Jughashvili's shop failed and he developed a serious drinking problem, wherefore he left his family and moved back to Tbilisi in 1884, working in a factory again. He had little contact with either his wife or son after that point, and little is known of his life from then on, except that he died in 1909 of cirrhosis.

Before he became a Bolshevik revolutionary and leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin was a promising poet.

Tbilisi Theological Academy and Seminary is a seminary in Tbilisi, Georgia. It operated from 1817 to 1919 under the name Tiflis Theological Seminary in the Georgian exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church. The facility closed during the wake of the Russian Revolution and the subsequent 1921 invasion of Georgia. The building housing the seminary closed in 1917, and one of the major buildings the seminary used was eventually repurposed in 1950 to become the Art Museum of Georgia.

Akaki Mgeladze was a Soviet politician. He served as First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party from 1952 to 1953, and before that was First Secretary of the Communist Party of Abkhazia from 1943 until 1951, as well as previously leading both the Georgian and Abkhazian Komsomol and Gruzneft.