Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Croatia have expanded since the turn of the 21st century, especially in the 2010s and 2020s. However, LGBT people still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. The status of same-sex relationships was first formally recognized in 2003 under a law dealing with unregistered cohabitations. As a result of a 2013 referendum, the Constitution of Croatia defines marriage solely as a union between a woman and man, effectively prohibiting same-sex marriage. Since the introduction of the Life Partnership Act in 2014, same-sex couples have effectively enjoyed rights equal to heterosexual married couples in almost all of its aspects, except adoption. In 2022, a final court judgement allowed same-sex adoption under the same conditions as for mixed-sex couples. Same-sex couples in Croatia can also apply for foster care since 2020. Croatian law forbids all discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression in all civil and state matters; any such identity is considered a private matter, and such information gathering for any purpose is forbidden as well.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Hungary face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Homosexuality is legal in Hungary for both men and women. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and sex is banned in the country. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the same legal rights available to heterosexual married couples. Registered partnership for same-sex couples was legalised in 2009, but same-sex marriage remains banned. The Hungarian government has passed legislation that restricts the civil rights of LGBT Hungarians – such as ending legal recognition of transgender Hungarians and banning LGBT content and displays for minors. This trend continues under the Fidesz government of Viktor Orbán. In June 2021, Hungary passed an anti-LGBT law on banning "homosexual and transexual propaganda" effective since 1 July. The law has been condemned by seventeen member states of the European Union. In July 2020, the European Commission started legal action against Hungary and Poland for violations of fundamental rights of LGBTQI people, stating: "Europe will never allow parts of our society to be stigmatized."

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Bulgaria face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex relationships are legal in Bulgaria, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned since 2004, with discrimination based on "gender change" being outlawed since 2015. In July 2019, a Bulgarian court recognized a same-sex marriage performed in France in a landmark ruling. For 2020, Bulgaria was ranked 37 of 49 European countries for LGBT rights protection by ILGA-Europe. Like most countries in Central and Eastern Europe, post-Communist Bulgaria holds socially conservative attitudes when it comes to such matters as homosexuality and transgender people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Finland are among the most advanced in the world. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity have been legal in Finland since 1971 with "promotion" thereof decriminalized and the age of consent equalized in 1999. Homosexuality was declassified as an illness in 1981. Discrimination based on sexual orientation in areas such as employment, the provision of goods and services, etc., was criminalized in 1995 and discrimination based on gender identity in 2005.

Latvia has recognised civil unions since 1 July 2024. On 9 November 2023, the Saeima passed legislation establishing same-sex civil unions conferring similar rights and obligations as marriage with the exception of adoption and inheritance rights. The bill was signed into law by President Edgars Rinkēvičs in January 2024, and took effect on 1 July 2024. This followed a ruling from the Constitutional Court of Latvia on 12 November 2020 that the Latvian Constitution entitles same-sex couples to receive the same benefits and protections afforded by Latvian law to married opposite-sex couples, and gave the Saeima until 1 June 2022 to enact a law protecting same-sex couples. In December 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that should the Saeima fail to pass civil union legislation before the 1 June 2022 deadline, same-sex couples may apply to a court to have their relationship recognized. The Saeima failed to meet this deadline, and the first same-sex union was recognized by the Administrative District Court on 30 May 2022.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Romania may face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Attitudes in Romania are generally conservative, with regard to the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender citizens. Nevertheless, the country has made significant changes in LGBT rights legislation since 2000. In the past two decades, it fully decriminalised homosexuality, introduced and enforced wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws, equalised the age of consent and introduced laws against homophobic hate crimes. Furthermore, LGBT communities have become more visible in recent years, as a result of events such as Bucharest's annual pride parade, Timișoara's Pride Week and Cluj-Napoca's Gay Film Nights festival.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in Iceland rank among the highest in the world. Icelandic culture is generally tolerant towards homosexuality and transgender individuals, and Reykjavík has a visible LGBT community. Iceland ranked first on the Equaldex Equality Index in 2023, and second after Malta according to ILGA-Europe's 2024 LGBT rights ranking, indicating it is one of the safest nations for LGBT people in Europe. Conversion therapy in Iceland has been illegal since 2023.

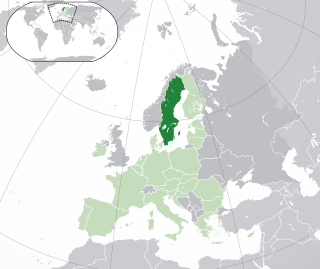

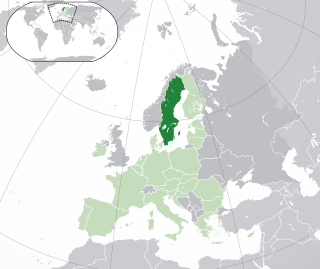

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Sweden are regarded as some of the most progressive in Europe and the world. Same-sex sexual activity was legalized in 1944 and the age of consent was equalized to that of heterosexual activity in 1972. Sweden also became the first country in the world to allow transgender people to change their legal gender post-sex reassignment surgery in 1972, whilst transvestism was declassified as an illness in 2009. Legislation allowing legal gender changes without hormone replacement therapy and sex reassignment surgery was passed in 2013.

Danish lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are some of the most extensive in the world. In 2023, ILGA-Europe ranked Denmark as the third most LGBT-supportive country in Europe. Polls consistently show that same-sex marriage support is nearly universal amongst the Danish population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Greece are regarded as the most advanced in Southeast Europe and among all the neighboring countries. Public opinion on homosexuality in Greece is generally regarded as culturally liberal, with civil partnerships being legally recognised since 2015 and same-sex marriage since 16 February 2024.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Montenegro face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Montenegro, but households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Moldova face legal and social challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same rights and benefits as households headed by opposite-sex couples. Same-sex unions are not recognized in the country, so consequently same-sex couples have little to no legal protection. Nevertheless, Moldova bans discrimination based on sexual orientation in the workplace, and same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1995.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Portugal are among the most advanced in the world; having improved substantially in the 21st century. After a long period of oppression during the Estado Novo, Portuguese society has become increasingly accepting of homosexuality, which was decriminalized in 1982, eight years after the Carnation Revolution. Portugal has wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws and is one of the few countries in the world to contain a ban on discrimination based on sexual orientation in its Constitution. On 5 June 2010, the state became the eighth in the world to recognize same-sex marriage. On 1 March 2011, a gender identity law, said to be one of the most advanced in the world, was passed to simplify the process of sex and name change for transgender people. Same-sex couples have been permitted to adopt since 1 March 2016.

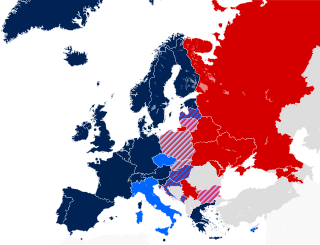

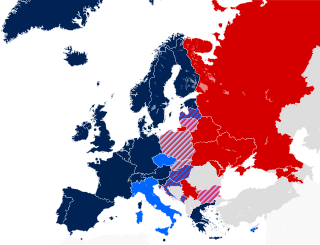

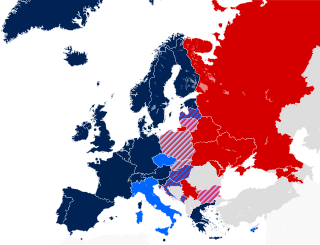

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. 22 of the 38 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further 11 European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of recognition for same-sex couples.

Hungary has recognized registered partnerships since 1 July 2009, offering same-sex couples nearly all the rights and benefits of marriage. Unregistered cohabitation for same-sex couples was recognised and placed on equal footing with the unregistered cohabitation of different-sex couples in 1996. However, same-sex marriage is prohibited by the 2011 Constitution of Hungary, which took effect in January 2012.

Baltic Pride is an annual LGBT+ pride parade rotating in turn between the capitals of the Baltic states; Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius. It is held in support of raising issues of tolerance and the rights of the LGBT community and is supported by ILGA-Europe. Since 2009, the main organisers have been Mozaīka, the National LGBT Rights Organization LGL Lithuanian Gay League, and the Estonian LGBT Association.

Debate has occurred throughout Europe over proposals to legalise same-sex marriage as well as same-sex civil unions. Currently 33 of the 50 countries and the 8 dependent territories in Europe recognise some type of same-sex union, among them most members of the European Union (24/27). Nearly 43% of the European population lives in jurisdictions where same-sex marriage is legal.

LGBT rights in the European Union are protected under the European Union's (EU) treaties and law. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in all EU member states and discrimination in employment has been banned since 2000. However, EU states have different laws when it comes to any greater protection, same-sex civil union, same-sex marriage, and adoption by same-sex couples.

The New Unity is a centre-right political alliance in Latvia. Its members are Unity and four other regional parties, and it is orientated towards liberal-conservatism and liberalism.