Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Czech Republic are granted some protections, but may still face legal difficulties not experienced by non-LGBT residents. In 2006, the country legalized registered partnerships for same-sex couples, and a bill legalizing same-sex marriage was being considered by the Parliament of the Czech Republic before its dissolution for the 2021 Czech legislative election, when it died in the committee stage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Hungary face legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Homosexuality is legal in Hungary for both men and women. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and sex is banned in the country. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the same legal rights available to heterosexual married couples. Registered partnership for same-sex couples was legalised in 2009, but same-sex marriage remains banned. The Hungarian government has passed legislation that restricts the civil rights of LGBT Hungarians – such as ending legal recognition of transgender Hungarians and banning LGBT content and displays for minors. This trend continues under the Fidesz government of Viktor Orbán. In June 2021, Hungary passed an anti-LGBT law on banning "homosexual and transexual propaganda" effective since 1 July. The law has been condemned by seventeen member states of the European Union. In July 2020, the European Commission started legal action against Hungary and Poland for violations of fundamental rights of LGBTQI people, stating: "Europe will never allow parts of our society to be stigmatized."

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Serbia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Serbia, and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is banned in areas such as employment, education, media, and the provision of goods and services, amongst others. Nevertheless, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in Austria have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now considered generally progressive. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Austria. Registered partnerships were introduced in 2010, giving same-sex couples some of the rights of marriage. Stepchild adoption was legalised in 2013, while full joint adoption was legalised by the Constitutional Court of Austria in 2016. On 5 December 2017, the Austrian Constitutional Court decided to legalise same-sex marriage, and the ruling went into effect on 1 January 2019.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Bosnia and Herzegovina may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Romania may face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Attitudes in Romania are generally conservative, with regard to the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender citizens. Nevertheless, the country has made significant changes in LGBT rights legislation since 2000. In the past two decades, it fully decriminalised homosexuality, introduced and enforced wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws, equalised the age of consent and introduced laws against homophobic hate crimes. Furthermore, LGBT communities have become more visible in recent years, as a result of events such as Bucharest's annual pride parade, Timișoara's Pride Week and Cluj-Napoca's Gay Film Nights festival.

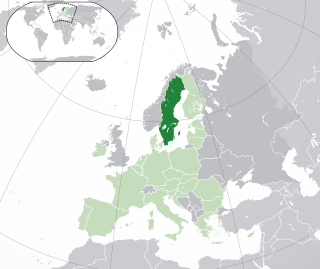

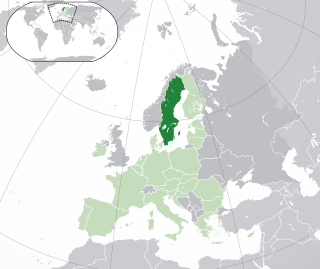

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Sweden are regarded as some of the most progressive in Europe and the world. Same-sex sexual activity was legalized in 1944 and the age of consent was equalized to that of heterosexual activity in 1972. Sweden also became the first country in the world to allow transgender people to change their legal gender post-sex reassignment surgery in 1972, whilst transvestism was declassified as an illness in 2009. Legislation allowing legal gender changes without hormone replacement therapy and sex reassignment surgery was passed in 2013.

Danish lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are some of the most extensive in the world. In 2023, ILGA-Europe ranked Denmark as the third most LGBT-supportive country in Europe. Polls consistently show that same-sex marriage support is nearly universal amongst the Danish population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Cyprus have evolved in recent years, but LGBTQ people still face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity were decriminalised in 1998, and civil unions which grant several of the rights and benefits of marriage have been legal since December 2015. Conversion therapy was banned in Cyprus in May 2023. However, adoption rights in Cyprus are reserved for heterosexual couples only.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights in Latvia have expanded substantially in recent years, although LGBT people still face various challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Latvia, but households headed by same-sex couples are ineligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples. Since May 2022, same-sex couples have been recognized as "family" by the Administrative District Court, which gives them some of the legal protections available to married (opposite-sex) couples; as of 2023 November, around 40 couples have been registered via this procedure. In November 2023 registered partnerships were codified into law. These partnerships are available to both same and different sex couples - since July 1, 2024 the implemented registered partnership law has the similar rights and obligations as married couples - with the exception of the title of marriage, and adoption or inheritance rights.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Lithuania have evolved rapidly over the years, although LGBT people still face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female expressions of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Lithuania, but neither civil same-sex partnership nor same-sex marriages are available, meaning that there is no legal recognition of same-sex couples.

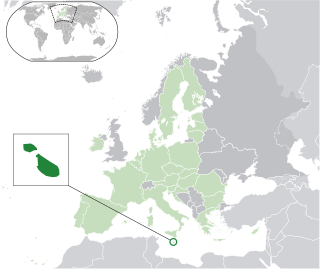

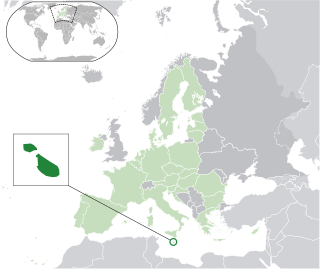

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Malta rank among the highest in the world. Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, the rights of the LGBTQ community received more awareness and same-sex sexual activity was legalized on 29 January 1973. The prohibition was already dormant by the 1890s.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Moldova face legal and social challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same rights and benefits as households headed by opposite-sex couples. Same-sex unions are not recognized in the country, so consequently same-sex couples have little to no legal protection. Nevertheless, Moldova bans discrimination based on sexual orientation in the workplace, and same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1995.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Portugal are among the most advanced in the world; having improved substantially in the 21st century. After a long period of oppression during the Estado Novo, Portuguese society has become increasingly accepting of homosexuality, which was decriminalized in 1982, eight years after the Carnation Revolution. Portugal has wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws and is one of the few countries in the world to contain a ban on discrimination based on sexual orientation in its Constitution. On 5 June 2010, the state became the eighth in the world to recognize same-sex marriage. On 1 March 2011, a gender identity law, said to be one of the most advanced in the world, was passed to simplify the process of sex and name change for transgender people. Same-sex couples have been permitted to adopt since 1 March 2016.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Slovenia have significantly evolved over time, and are considered among the most advanced of the former communist countries. Slovenia was the first post-communist country to have legalised same-sex marriage, and anti-discrimination laws regarding sexual orientation and gender identity have existed nationwide since 2016.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Namibia have expanded in the 21st century, although LGBT people still have limited legal protections. Namibia's colonial-era laws criminalising male homosexuality were historically unenforced, and were overturned by the country's High Court in 2024.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Kosovo have improved in recent years, most notably with the adoption of the new Constitution, banning discrimination based on sexual orientation. Kosovo remains one of the few Muslim-majority countries that hold regular pride parades.

Bulgaria does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions. Though these issues have been discussed frequently over the past few years, no law on the matter has passed the National Assembly. In September 2023, the European Court of Human Rights ordered the government to establish a legal framework recognizing same-sex unions.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in North Macedonia face discrimination and some legal and social challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity have been legal in North Macedonia since 1996, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Curaçao have similar rights to non-LGBT people. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity are legal in Curaçao. Discrimination on the basis of "heterosexual or homosexual orientation" is outlawed by the Curaçao Criminal Code.