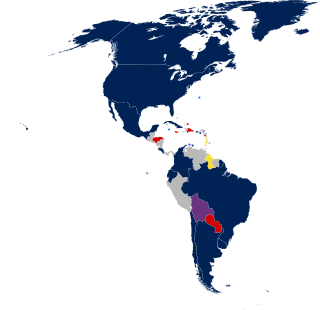

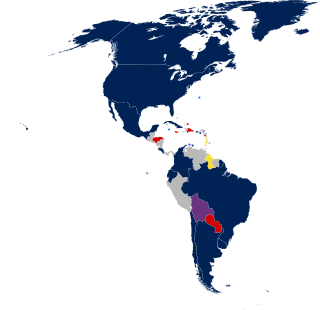

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Chile since 10 March 2022. The path to legalization began in June 2021 when President Sebastián Piñera announced his administration's intention to sponsor a bill for this cause. The Chilean Senate passed the legislation on 21 July 2021, followed by the Chamber of Deputies on 23 November 2021. Due to disagreements between the two chambers of the National Congress on certain aspects of the bill, a mixed commission was formed to resolve these issues. A unified version of the bill was approved on 7 December 2021. President Piñera signed it into law on 9 December, and it was published in the country's official gazette on 10 December. The law took effect 90 days later, and the first same-sex marriages occurred on 10 March 2022. Chile was the sixth country in South America, the seventh in Latin America and the 29th in the world to legalize same-sex marriage.

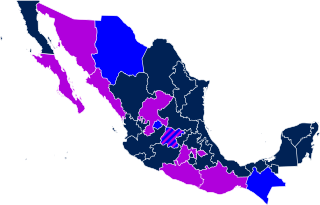

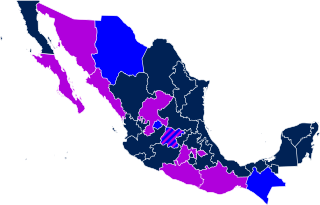

Same-sex marriage is legally recognized and performed throughout Mexico since 31 December 2022. On 10 August 2010 the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation ruled that same-sex marriages performed anywhere within Mexico must be recognized by the 31 states without exception, and fundamental spousal rights except for adoption have also applied to same-sex couples across the country. Mexico was the fifth country in North America and the 33rd worldwide to allow same-sex couples to marry nationwide.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Costa Rica since May 26, 2020 as a result of a ruling by the Supreme Court of Justice. Costa Rica was the first country in Central America to recognize and perform same-sex marriages, the third in North America after Canada and the United States, and the 28th to do so worldwide.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Colombia since 28 April 2016 in accordance with a 6–3 ruling from the Constitutional Court of Colombia that banning same-sex marriage is unconstitutional under the Constitution of Colombia. The decision took effect immediately, and made Colombia the fourth country in South America to legalize same-sex marriage, after Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. The first same-sex marriage was performed in Cali on 24 May 2016.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Honduras face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Honduras.

Many countries in the Americas grant legal recognition to same-sex unions, with almost 85 percent of people in both North America and South America living in jurisdictions providing marriage rights to same-sex couples.

Laws governing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are complex and diverse in the Americas, and acceptance of LGBTQ persons varies widely.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Ecuador since 8 July 2019 in accordance with a Constitutional Court ruling issued on 12 June 2019 that the ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional under the Constitution of Ecuador. The court held that the Constitution required the government to license and recognise same-sex marriages. It focused its ruling on an advisory opinion issued by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in January 2018 that member states should grant same-sex couples "accession to all existing domestic legal systems of family registration, including marriage, along with all rights that derive from marriage". The ruling took effect upon publication in the government gazette on 8 July.

El Salvador does not recognize same-sex marriage, civil unions or any other legal union for same-sex couples. A proposal to constitutionally ban same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples was rejected twice in 2006, and once again in April 2009 after the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) refused to grant the measure the four votes it needed to be ratified.

Paraguay does not recognize same-sex marriage or civil unions. The Constitution of Paraguay has explicitly prohibited same-sex marriage since 1992, and de facto unions are only available to opposite-sex couples.

Same-sex marriage is legal in the following countries: Andorra, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay. Same-sex marriage is recognized, but not performed in Israel.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Jalisco since a unanimous ruling by the Mexican Supreme Court on 26 January 2016 striking down the state's same-sex marriage ban as unconstitutional under Articles 1 and 4 of the Constitution of Mexico. The ruling was published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 21 April; however, some municipalities refused to marry same-sex couples until being ordered by Congress to do so on 12 May 2016. The state Congress passed a bill codifiying same-sex marriage into law on 6 April 2022.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Chiapas in accordance with a Supreme Court ruling issued on 11 July 2017 that the ban on same-sex marriage violated the equality and non-discrimination provisions of Articles 1 and 4 of the Constitution of Mexico. The ruling, published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 11 May 2018, legalized same-sex marriage in the state of Chiapas.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Colima since 12 June 2016. On 25 May 2016, a bill to legalise same-sex marriage passed the Congress of Colima and was published as law in the state's official journal on 11 June. It came into effect the next day. Colima had previously recognized same-sex civil unions, but this "separate but equal" treatment of granting civil unions to same-sex couples and marriage to opposite-sex couples was declared discriminatory by the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation in June 2015. Congress had passed a civil union bill in 2013 but repealed it in 2016 shortly before the legalization of same-sex marriage.

Same-sex marriage is legal in Puebla in accordance with a ruling from the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation. On 1 August 2017, the Supreme Court ruled that the same-sex marriage ban containted in the state's Civil Code violated Articles 1 and 4 of the Constitution of Mexico, legalizing same-sex marriage in the state of Puebla. The ruling was officially published in the Official Journal of the Federation on 16 February 2018.

Same-sex unions are currently not recognized in Honduras. Since 2005, the Constitution of Honduras has explicitly banned same-sex marriage. In January 2022, the Supreme Court dismissed a challenge to this ban, but a request for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to review whether the ban violates the American Convention on Human Rights is pending. A same-sex marriage bill was introduced to Congress in May 2022.

Same-sex marriage is legal in Nuevo León in accordance with a ruling from the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation issued on 19 February 2019 that the state's ban on same-sex marriage violated the Constitution of Mexico. The ruling came into effect on 31 May 2019 upon publication in the Official Journal of the Federation. By statute, in Mexico, if any five rulings from the courts on a single issue result in the same outcome, legislatures are bound to change the law. In the case of Nuevo León, almost 20 amparos were decided with the same outcome, yet the state did not act. On 19 February 2019, the Supreme Court issued a definitive ruling in an action of unconstitutionality, declaring the state's same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional, void and unenforceable.

Same-sex marriage is legal in Aguascalientes in accordance with a ruling from the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation on 2 April 2019 that the state's ban on same-sex marriage violated Articles 1 and 4 of the Constitution of Mexico. The ruling came into effect upon publication in the Official Gazette of the Federation on 16 August 2019, legalizing same-sex marriage in Aguascalientes.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Baja California Sur since 29 June 2019. On 27 June, the state Congress passed a bill opening marriage to same-sex couples. It was published in the official state gazette on 28 June and took effect the following day, legalizing same-sex marriage in Baja California Sur.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Tamaulipas since 19 November 2022. On 26 October 2022, the Congress of Tamaulipas passed a bill to legalize same-sex marriage in a 23–12 vote. It was published in the official state journal on 18 November, and took effect the following day. Tamaulipas was the second-to-last Mexican state to legalize same-sex marriage.

![Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.

.mw-parser-output .legend{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .legend-color{display:inline-block;min-width:1.25em;height:1.25em;line-height:1.25;margin:1px 0;text-align:center;border:1px solid black;background-color:transparent;color:black}.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}

Same-sex marriage

Other type of partnership

Unregistered cohabitation

Country subject to IACHR ruling

No recognition of same-sex couples

Constitution limits marriage to opposite-sex couples

Same-sex sexual activity illegal but law not enforced

.mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:": "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:" * ";font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:" (";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:")";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:" "counter(listitem)"\a0 "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:" ("counter(listitem)"\a0 "}

.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}@media(prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}}@media print{.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:none!important}}

v

t

e Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg/280px-Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg.png)