Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Ecuador have evolved significantly in the past decades. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Ecuador and same-sex couples can enter into civil unions and same-sex marriages.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Venezuela face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Venezuela, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Also, same-sex marriage and de facto unions are constitutionally banned since 1999.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Chile have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now quite progressive.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Costa Rica have evolved significantly in the past decades. Same-sex sexual relations have been legal since 1971. In January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights made mandatory the approbation of same-sex marriage, adoption for same-sex couples and the removal of people's sex from all Costa Rican ID cards issued since October 2018. The Costa Rican Government announced that it would apply the rulings in the following months. In August 2018, the Costa Rican Supreme Court ruled against the country's same-sex marriage ban, and gave the Legislative Assembly 18 months to reform the law accordingly, otherwise the ban would be abolished automatically. Same-sex marriage became legal on 26 May 2020.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Mexico expanded in the 21st century, keeping with worldwide legal trends. The intellectual influence of the French Revolution and the brief French occupation of Mexico (1862–67) resulted in the adoption of the Napoleonic Code, which decriminalized same-sex sexual acts in 1871. Laws against public immorality or indecency, however, have been used to prosecute persons who engage in them.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Argentina rank among the highest in the world. Upon legalising same-sex marriage on 15 July 2010, Argentina became the first country in Latin America, the second in the Americas, and the tenth in the world to do so. Following Argentina's transition to a democracy in 1983, its laws have become more inclusive and accepting of LGBT people, as has public opinion.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Uruguay rank among the highest in the world. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal with an equal age of consent since 1934. Anti-discrimination laws protecting LGBT people have been in place since 2004. Civil unions for same-sex couples have been allowed since 2008 and same-sex marriages since 2013, in accordance with the nation's same-sex marriage law passed in early 2013. Additionally, same-sex couples have been allowed to jointly adopt since 2009 and gays, lesbians and bisexuals are allowed to serve openly in the military. Finally, in 2018, a new law guaranteed the human rights of the trans population.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Angola have seen improvements in the early 21st century. In November 2020, the National Assembly approved a new penal code, which legalised consenting same-sex sexual activity. Additionally, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned, making Angola one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBTQ people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Colombia have advanced significantly in the 21st century, and are now quite progressive. Consensual same-sex sexual activity in Colombia was decriminalized in 1981. Between February 2007 and April 2008, three rulings of the Constitutional Court granted registered same-sex couples the same pension, social security and property rights as registered heterosexual couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Nicaragua face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Nicaragua. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned in certain areas, including in employment and access to health services.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Panama face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Panama, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal benefits and protections available to opposite-sex married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, non-binary and otherwise queer, non-cisgender, non-heterosexual citizens of El Salvador face considerable legal and social challenges not experienced by fellow heterosexual, cisgender Salvadorans. While same-sex sexual activity between all genders is legal in the country, same-sex marriage is not recognized; thus, same-sex couples—and households headed by same-sex couples—are not eligible for the same legal benefits provided to heterosexual married couples.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Peru face some legal challenges not experienced by other residents. Same-sex sexual activity among consenting adults is legal. However, households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples.

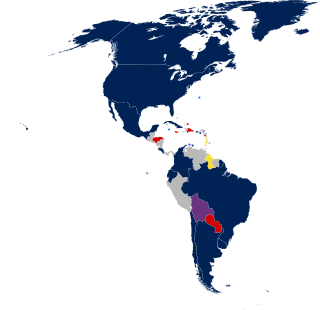

Laws governing lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are complex and diverse in the Americas, and acceptance of LGBTQ persons varies widely.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in the Dominican Republic do not possess the same legal protections as non-LGBTQ residents, and face social challenges that are not experienced by other people. While the Dominican Criminal Code does not expressly prohibit same-sex sexual relations or cross-dressing, it also does not address discrimination or harassment on the account of sexual orientation or gender identity, nor does it recognize same-sex unions in any form, whether it be marriage or partnerships. Households headed by same-sex couples are also not eligible for any of the same rights given to opposite-sex married couples, as same-sex marriage is constitutionally banned in the country.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Bolivia have expanded significantly in the 21st century. Both male and female same-sex sexual activity and same-sex civil unions are legal in Bolivia. The Bolivian Constitution bans discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. In 2016, Bolivia passed a comprehensive gender identity law, seen as one of the most progressive laws relating to transgender people in the world.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Guatemala face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female forms of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Guatemala.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Paraguay face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Paraguay, but same-sex couples and households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for all of the same legal protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Paraguay remains one of the few conservative countries in South America regarding LGBT rights.

Same-sex unions are currently not recognized in Honduras. Since 2005, the Constitution of Honduras has explicitly banned same-sex marriage. In January 2022, the Supreme Court dismissed a challenge to this ban, but a request for the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to review whether the ban violates the American Convention on Human Rights is pending. A same-sex marriage bill was introduced to Congress in May 2022.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Tamaulipas since 19 November 2022. On 26 October 2022, the Congress of Tamaulipas passed a bill to legalize same-sex marriage in a 23–12 vote. It was published in the official state journal on 18 November, and took effect the following day. Tamaulipas was the second-to-last Mexican state to legalize same-sex marriage.

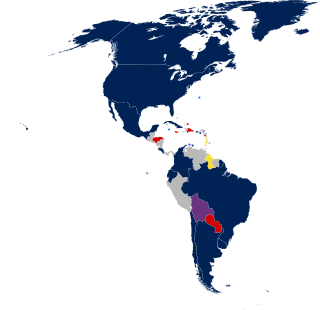

![Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.

.mw-parser-output .legend{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .legend-color{display:inline-block;min-width:1.25em;height:1.25em;line-height:1.25;margin:1px 0;text-align:center;border:1px solid black;background-color:transparent;color:black}.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}

Same-sex marriage

Other type of partnership

Unregistered cohabitation

Country subject to IACHR ruling

No recognition of same-sex couples

Constitution limits marriage to opposite-sex couples

Same-sex sexual activity illegal but law not enforced

.mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:": "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:" * ";font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:" (";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:")";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:" "counter(listitem)"\a0 "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:" ("counter(listitem)"\a0 "}

.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}@media(prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}}@media print{.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:none!important}}

v

t

e Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg/280px-Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg.png)