Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) rights in Mexico expanded in the 21st century, keeping with worldwide legal trends. The intellectual influence of the French Revolution and the brief French occupation of Mexico (1862–67) resulted in the adoption of the Napoleonic Code, which decriminalized same-sex sexual acts in 1871. Laws against public immorality or indecency, however, have been used to prosecute persons who engage in them.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of New Hampshire enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people, with most advances in LGBT rights occurring in the state within the past two decades. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in New Hampshire, and the state began offering same-sex couples the option of forming a civil union on January 1, 2008. Civil unions offered most of the same protections as marriages with respect to state law, but not the federal benefits of marriage. Same-sex marriage in New Hampshire has been legally allowed since January 1, 2010, and one year later New Hampshire's civil unions expired, with all such unions converted to marriages. New Hampshire law has also protected against discrimination based on sexual orientation since 1998 and gender identity since 2018. Additionally, a conversion therapy ban on minors became effective in the state in January 2019. In effect since January 1, 2024, the archaic common-law "gay panic defence" was formally abolished; by legislation implemented within August 2023.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Michigan enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Michigan in June 2024 was ranked "the most welcoming U.S. state for LGBT individuals". Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Michigan under the U.S. Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy law. Same-sex marriage was legalised in accordance with 2015's Obergefell v. Hodges decision. Discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity is unlawful since July 2022, was re-affirmed by the Michigan Supreme Court - under and by a 1976 statewide law, that explicitly bans discrimination "on the basis of sex". The Michigan Civil Rights Commission have also ensured that members of the LGBT community are not discriminated against and are protected in the eyes of the law since 2018 and also legally upheld by the Michigan Supreme Court in 2022. In March 2023, a bill passed the Michigan Legislature by a majority vote - to formally codify both "sexual orientation and gender identity" anti-discrimination protections embedded within Michigan legislation. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed the bill on March 16, 2023. In 2024, Michigan repealed “the last ban on commercial surrogacy within the US” - for individuals and couples and reformed the parentage laws, that acknowledges same sex couples and their families with children.

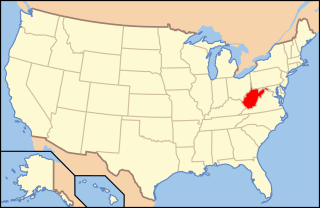

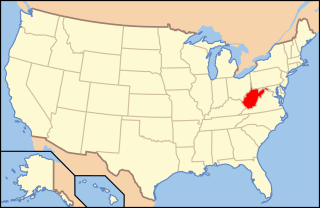

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of West Virginia face legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT persons. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1976, and same-sex marriage has been recognized since October 2014. West Virginia statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Minnesota have the same legal rights as non-LGBTQ people. Minnesota became the first U.S. state to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in 1993, protecting LGBTQ people from discrimination in the fields of employment, housing, and public accommodations. In 2013, the state legalized same-sex marriage, after a bill allowing such marriages was passed by the Minnesota Legislature and subsequently signed into law by Governor Mark Dayton. This followed a 2012 ballot measure in which voters rejected constitutionally banning same-sex marriage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of New Jersey have the same legal rights as non-LGBTQ people. LGBT individuals in New Jersey enjoy strong protections from discrimination, and have had the same marriage rights as heterosexual people since October 21, 2013.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Florida have federal protections, but many face legal difficulties on the state level that are not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity became legal in the state after the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Lawrence v. Texas on June 26, 2003, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since January 6, 2015. Discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations is outlawed following the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County. In addition, several cities and counties, comprising about 55 percent of Florida's population, have enacted anti-discrimination ordinances. These include Jacksonville, Miami, Tampa, Orlando, St. Petersburg, Tallahassee and West Palm Beach, among others. Conversion therapy is also banned in a number of cities in the state, mainly in the Miami metropolitan area, but has been struck down by the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals. In September 2023, Lake Worth Beach, Florida became an official "LGBT sanctuary city" to protect and defend LGBT rights.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Massachusetts enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. The U.S. state of Massachusetts is one of the most LGBT-supportive states in the country. In 2004, it became the first U.S. state to grant marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the decision in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, and the sixth jurisdiction worldwide, after the Netherlands, Belgium, Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec.

The U.S. state of New York has generally been seen as socially liberal in regard to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) rights. LGBT travel guide Queer in the World states, "The fabulosity of Gay New York is unrivaled on Earth, and queer culture seeps into every corner of its five boroughs". The advocacy movement for LGBT rights in the state has been dated as far back as 1969 during the Stonewall riots in New York City. Same-sex sexual activity between consenting adults has been legal since the New York v. Onofre case in 1980. Same-sex marriage has been legal statewide since 2011, with some cities recognizing domestic partnerships between same-sex couples since 1998. Discrimination protections in credit, housing, employment, education, and public accommodation have explicitly included sexual orientation since 2003 and gender identity or expression since 2019. Transgender people in the state legally do not have to undergo sex reassignment surgery to change their sex or gender on official documents since 2014. In addition, both conversion therapy on minors and the gay and trans panic defense have been banned since 2019. Since 2021, commercial surrogacy has been legally available within New York State.

The establishment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the U.S. state of Connecticut is a recent phenomenon, with most advances in LGBT rights taking place in the late 20th century and early 21st century. Connecticut was the second U.S. state to enact two major pieces of pro-LGBT legislation; the repeal of the sodomy law in 1971 and the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2008. State law bans unfair discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations, and both conversion therapy and the gay panic defense are outlawed in the state.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the U.S. state of Iowa have evolved significantly in the 21st century. Iowa began issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples on April 27, 2009 following a ruling by the Iowa Supreme Court, making Iowa the fourth U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage. Same-sex couples may also adopt, and state laws ban discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Hawaii enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1973; Hawaii being one of the first six states to legalize it. In 1993, a ruling by the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court made Hawaii the first state to consider legalizing same-sex marriage. Following the approval of the Hawaii Marriage Equality Act in November 2013, same-sex couples have been allowed to marry on the islands. Additionally, Hawaii law prohibits discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity, and the use of conversion therapy on minors has been banned since July 2018. Gay and lesbian couples enjoy the same rights, benefits and treatment as opposite-sex couples, including the right to marry and adopt.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Wisconsin enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. However, the transgender community may face some legal issues not experienced by cisgender residents, due in part to discrimination based on gender identity not being included in Wisconsin's anti-discrimination laws, nor is it covered in the state's hate crime law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in Wisconsin since October 6, 2014, when the U.S. Supreme Court refused to consider an appeal in the case of Wolf v. Walker. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned statewide in Wisconsin, and sexual orientation is a protected class in the state's hate crime laws. It approved such protections in 1982, making it the first state in the United States to do so.

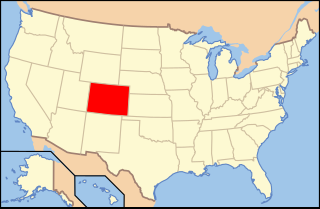

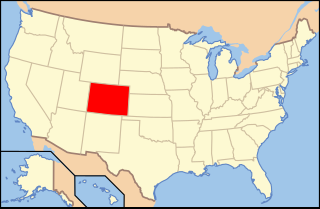

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Colorado enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Colorado since 1972. Same-sex marriage has been recognized since October 2014, and the state enacted civil unions in 2013, which provide some of the rights and benefits of marriage. State law also prohibits discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations and the use of conversion therapy on minors. In July 2020, Colorado became the 11th US state to abolish the gay panic defense.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Pennsylvania. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Pennsylvania was the final Mid-Atlantic state without same-sex marriage, indeed lacking any form of same-sex recognition law until its statutory ban was overturned on May 20, 2014.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in Puerto Rico have gained some legal rights in recent years. Same sex relationships have been legal in Puerto Rico since 2003, and same-sex marriage and adoptions are also permitted. U.S. federal hate crime laws apply in Puerto Rico.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2016.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2017.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2019.

This is a list of notable events in the history of LGBT rights that took place in the year 2020.