Heterosexism is a system of attitudes, bias, and discrimination in favor of heterosexuality and heterosexual relationships. According to Elizabeth Cramer, it can include the belief that all people are or should be heterosexual and that heterosexual relationships are the only norm and therefore superior.

Homosexuality in Haitian Vodou is religiously acceptable and homosexuals are allowed to participate in all religious activities. However, in West African countries with major conservative Christian and Islamic views on LGBTQ people, the attitudes towards them may be less tolerant if not openly hostile and these influences are reflected in African diaspora religions following Atlantic slave trade which includes Haitian Vodou.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ) people in the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Afghan members of the LGBT community are forced to keep their gender identity and sexual orientation secret, in fear of violence and the death penalty. The religious nature of the country has limited any opportunity for public discussion, with any mention of homosexuality and related terms deemed taboo.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Romania may face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Attitudes in Romania are generally conservative, with regard to the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender citizens. Nevertheless, the country has made significant changes in LGBT rights legislation since 2000. In the past two decades, it fully decriminalised homosexuality, introduced and enforced wide-ranging anti-discrimination laws, equalised the age of consent and introduced laws against homophobic hate crimes. Furthermore, LGBT communities have become more visible in recent years, as a result of events such as Bucharest's annual pride parade, Timișoara's Pride Week and Cluj-Napoca's Gay Film Nights festival.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Cuba have significantly varied throughout modern history. Cuba is now considered generally progressive, with vast improvements in the 21st century for such rights. Following the 2022 Cuban Family Code referendum, there is legal recognition of the right to marriage, unions between people of the same sex, same-sex adoption and non-commercial surrogacy as part of one of the most progressive Family Codes in Latin America. Until the 1990s, the LGBT community was marginalized on the basis of heteronormativity, traditional gender roles, politics and strict criteria for moralism. It was not until the 21st century that the attitudes and acceptance towards LGBT people changed to be more tolerant.

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who identify or are perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, or antipathy, may be based on irrational fear and may sometimes be attributed to religious beliefs.

Scott Long is a US-born activist for international human rights, primarily focusing on the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people. He founded the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Rights Program at Human Rights Watch, the first-ever program on LGBT rights at a major "mainstream" human rights organization, and served as its executive director from May 2004 - August 2010. He later was a visiting fellow in the Human Rights Program of Harvard Law School from 2011 to 2012.

Joël Gustave Nana Ngongang (1982–2015), frequently known as Joel Nana, was a leading African LGBT human rights advocate and HIV/AIDS activist. Nana's career as a human rights advocate spanned numerous African countries, including Nigeria, Senegal and South Africa, in addition to his native Cameroon. He was the Chief Executive Officer of Partners for Rights and Development (Paridev) a boutique consulting firm on human rights, development and health in Africa at the time of his death. Prior to that position, he was the founding Executive Director of the African Men for Sexual Health and Rights (AMSHeR) an African thought and led coalition of LGBT/MSM organizations working to address the vulnerability of MSM to HIV. Mr Nana worked in various national and international organizations, including the Africa Research and Policy Associate at the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC), as a Fellow at Behind the Mask, a Johannesburg-based non-profit media organisation publishing a news website concerning gay and lesbian affairs in Africa, he wrote on numerous topics in the area of African LGBT and HIV/AIDS issues and was a frequent media commentator. Nana died on October 15, 2015, after a brief illness.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Angola have seen improvements in the early 21st century. In November 2020, the National Assembly approved a new penal code, which legalised consenting same-sex sexual activity. Additionally, employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation has been banned, making Angola one of the few African countries to have such protections for LGBTQ people.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Botswana face legal issues not experienced by non-LGBTQ citizens. Both female and male same-sex sexual acts have been legal in Botswana since 11 June 2019 after a unanimous ruling by the High Court of Botswana. Despite an appeal by the government, the ruling was upheld by the Botswana Court of Appeal on 29 November 2021.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Nicaragua face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Both male and female types of same-sex sexual activity are legal in Nicaragua. Discrimination based on sexual orientation is banned in certain areas, including in employment and access to health services.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Somalia face severe challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Consensual same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women. In areas controlled by al-Shabab, and in Jubaland, capital punishment is imposed for such sexual activity. In other areas, where Sharia does not apply, the civil law code specifies prison sentences of up to three years as penalty. LGBT people are regularly prosecuted by the government and additionally face stigmatization among the broader population. Stigmatization and criminalisation of homosexuality in Somalia occur in a legal and cultural context where 99% of the population follow Islam as their religion, while the country has had an unstable government and has been subjected to a civil war for decades.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, non-binary and otherwise queer, non-cisgender, non-heterosexual citizens of El Salvador face considerable legal and social challenges not experienced by fellow heterosexual, cisgender Salvadorans. While same-sex sexual activity between all genders is legal in the country, same-sex marriage is not recognized; thus, same-sex couples—and households headed by same-sex couples—are not eligible for the same legal benefits provided to heterosexual married couples.

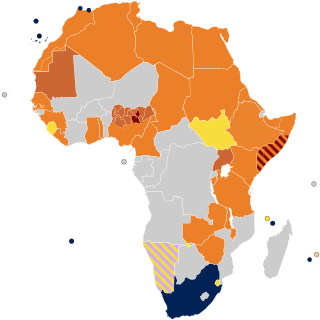

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Zambia face significant challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is illegal for both men and women in Zambia. Formerly a colony of the British Empire, Zambia inherited the laws and legal system of its colonial occupiers upon independence in 1964. Laws concerning homosexuality have largely remained unchanged since then, and homosexuality is covered by sodomy laws that also proscribe bestiality. Social attitudes toward LGBT people are mostly negative and coloured by perceptions that homosexuality is immoral and a form of insanity. However, in recent years, younger generations are beginning to show positive and open minded attitudes towards their LGBT peers.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Lesotho face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Lesotho does not recognise same-sex marriages or civil unions, nor does it ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.

Corrective rape, also called curative rape or homophobic rape, is a hate crime in which somebody is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation. The common intended consequence of the rape, as claimed by the perpetrator, is to turn the person heterosexual.

Homosexuality, as a phenomenon and as a behavior, has existed throughout all eras in human societies.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

Homophobia in ethnic minority communities is any negative prejudice or form of discrimination in ethnic minority communities worldwide towards people who identify as–or are perceived as being–lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT), known as homophobia. This may be expressed as antipathy, contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred, irrational fear, and is sometimes related to religious beliefs. A 2006 study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in the UK found that while religion can have a positive function in many LGB Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) communities, it can also play a role in supporting homophobia.

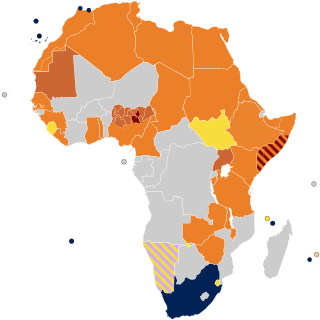

![Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.

.mw-parser-output .legend{page-break-inside:avoid;break-inside:avoid-column}.mw-parser-output .legend-color{display:inline-block;min-width:1.25em;height:1.25em;line-height:1.25;margin:1px 0;text-align:center;border:1px solid black;background-color:transparent;color:black}.mw-parser-output .legend-text{}

Same-sex marriage

Other type of partnership

Unregistered cohabitation

Country subject to IACHR ruling

No recognition of same-sex couples

Constitution limits marriage to opposite-sex couples

Same-sex sexual activity illegal but law not enforced

.mw-parser-output .hlist dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul{margin:0;padding:0}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt,.mw-parser-output .hlist li{margin:0;display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist.inline ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist dl ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ol ul,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul dl,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ol,.mw-parser-output .hlist ul ul{display:inline}.mw-parser-output .hlist .mw-empty-li{display:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dt::after{content:": "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li::after{content:" * ";font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li:last-child::after{content:none}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:first-child::before{content:" (";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dd li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt li:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dd:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li dt:last-child::after,.mw-parser-output .hlist li li:last-child::after{content:")";font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol{counter-reset:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li{counter-increment:listitem}.mw-parser-output .hlist ol>li::before{content:" "counter(listitem)"\a0 "}.mw-parser-output .hlist dd ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist dt ol>li:first-child::before,.mw-parser-output .hlist li ol>li:first-child::before{content:" ("counter(listitem)"\a0 "}

.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:inline;font-size:88%;font-weight:normal}.mw-parser-output .navbar-collapse{float:left;text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .navbar-boxtext{word-spacing:0}.mw-parser-output .navbar ul{display:inline-block;white-space:nowrap;line-height:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::before{margin-right:-0.125em;content:"[ "}.mw-parser-output .navbar-brackets::after{margin-left:-0.125em;content:" ]"}.mw-parser-output .navbar li{word-spacing:-0.125em}.mw-parser-output .navbar a>span,.mw-parser-output .navbar a>abbr{text-decoration:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-mini abbr{font-variant:small-caps;border-bottom:none;text-decoration:none;cursor:inherit}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-full{font-size:114%;margin:0 7em}.mw-parser-output .navbar-ct-mini{font-size:114%;margin:0 4em}html.skin-theme-clientpref-night .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}@media(prefers-color-scheme:dark){html.skin-theme-clientpref-os .mw-parser-output .navbar li a abbr{color:var(--color-base)!important}}@media print{.mw-parser-output .navbar{display:none!important}}

v

t

e Homosexuality laws in Central America and the Caribbean Islands.svg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg/280px-Homosexuality_laws_in_Central_America_and_the_Caribbean_Islands.svg.png)