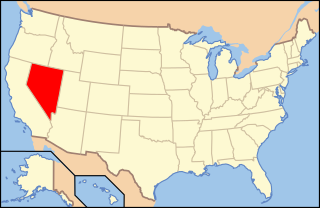

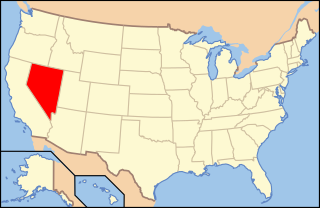

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Nevada enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex marriage has been legal since October 8, 2014, due to the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling in Sevcik v. Sandoval. Same-sex couples may also enter a domestic partnership status that provides many of the same rights and responsibilities as marriage. However, domestic partners lack the same rights to medical coverage as their married counterparts and their parental rights are not as well defined. Same-sex couples are also allowed to adopt, and state law prohibits unfair discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, among other categories, in employment, housing and public accommodations. In addition, conversion therapy on minors is outlawed in the state.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Wyoming may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Wyoming since 1977, and same-sex marriage was legalized in the state in October 2014. Wyoming statutes do not address discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. In addition, the cities of Jackson, Casper, and Laramie have enacted ordinances outlawing discrimination in housing and public accommodations that cover sexual orientation and gender identity.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Louisiana may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Louisiana as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas. Same-sex marriage has been recognized in the state since June 2015 as a result of the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges.

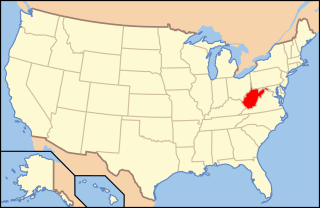

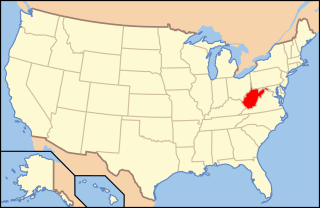

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of West Virginia face legal challenges not faced by non-LGBT persons. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1976, and same-sex marriage has been recognized since October 2014. West Virginia statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Delaware enjoy the same legal protections as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Delaware since January 1, 1973. On January 1, 2012, civil unions became available to same-sex couples, granting them the "rights, benefits, protections, and responsibilities" of married persons. Delaware legalized same-sex marriage on July 1, 2013.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of New Jersey have the same legal rights as non-LGBTQ people. LGBT individuals in New Jersey enjoy strong protections from discrimination, and have had the same marriage rights as heterosexual people since October 21, 2013.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Georgia enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. LGBTQ rights in the state have been a recent occurrence, with most improvements occurring from the 2010s onward. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1998, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy law. Same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since 2015, in accordance with Obergefell v. Hodges. In addition, the state's largest city Atlanta, has a vibrant LGBTQ community and holds the biggest Pride parade in the Southeast. The state's hate crime laws, effective since June 26, 2020, explicitly include sexual orientation.

The establishment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the U.S. state of Connecticut is a recent phenomenon, with most advances in LGBT rights taking place in the late 20th century and early 21st century. Connecticut was the second U.S. state to enact two major pieces of pro-LGBT legislation; the repeal of the sodomy law in 1971 and the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2008. State law bans unfair discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations, and both conversion therapy and the gay panic defense are outlawed in the state.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Hawaii enjoy the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity has been legal since 1973; Hawaii being one of the first six states to legalize it. In 1993, a ruling by the Hawaiʻi Supreme Court made Hawaii the first state to consider legalizing same-sex marriage. Following the approval of the Hawaii Marriage Equality Act in November 2013, same-sex couples have been allowed to marry on the islands. Additionally, Hawaii law prohibits discrimination on the basis of both sexual orientation and gender identity, and the use of conversion therapy on minors has been banned since July 2018. Gay and lesbian couples enjoy the same rights, benefits and treatment as opposite-sex couples, including the right to marry and adopt.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania enjoy most of the same rights as non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Pennsylvania. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. Pennsylvania was the final Mid-Atlantic state without same-sex marriage, indeed lacking any form of same-sex recognition law until its statutory ban was overturned on May 20, 2014.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Arkansas face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Arkansas. Same-sex marriage became briefly legal through a court ruling on May 9, 2014, subject to court stays and appeals. In June 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell v. Hodges that laws banning same-sex marriage are unconstitutional, legalizing same-sex marriage in the United States nationwide including in Arkansas. Nonetheless, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity was not banned in Arkansas until the Supreme Court banned it nationwide in Bostock v. Clayton County in 2020.

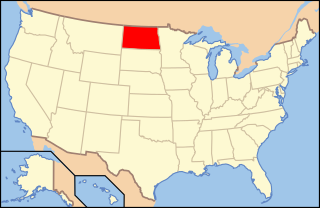

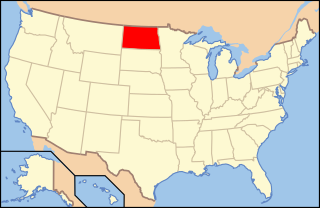

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of North Dakota may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in North Dakota, and same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples; same-sex marriage has been legal since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. State statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law.

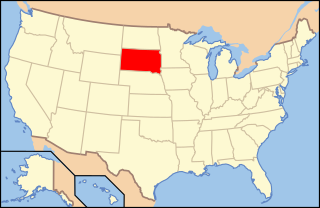

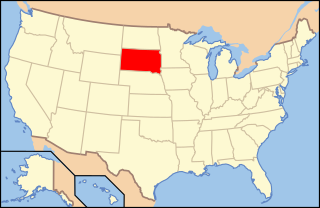

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of South Dakota may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in South Dakota, and same-sex marriages have been recognized since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. State statutes do not address discrimination on account of sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of South Carolina may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in South Carolina as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy laws. Same-sex couples and families headed by same-sex couples are eligible for all of the protections available to opposite-sex married couples. However, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity is not banned statewide.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Nebraska may face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Nebraska, and same-sex marriage has been recognized since June 2015 as a result of Obergefell v. Hodges. The state prohibits discrimination on account of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment and housing following the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County and a subsequent decision of the Nebraska Equal Opportunity Commission. In addition, the state's largest city, Omaha, has enacted protections in public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Kentucky still face some legal challenges not experienced by other people. Same-sex sexual activity in Kentucky has been legally permitted since 1992, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy statute for same-sex couples. Same-sex marriage is legal in Kentucky under the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges. The decision, which struck down Kentucky's statutory and constitutional bans on same-sex marriages and all other same-sex marriage bans elsewhere in the country, was handed down on June 26, 2015.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Idaho face some legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ people. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Idaho, and same-sex marriage has been legal in the state since October 2014. State statutes do not address discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. A number of cities and counties provide further protections, namely in housing and public accommodations. A 2019 Public Religion Research Institute opinion poll showed that 71% of Idahoans supported anti-discrimination legislation protecting LGBTQ people, and a 2016 survey by the same pollster found majority support for same-sex marriage.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Kansas have federal protections, but many face some legal challenges on the state level that are not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Kansas under the US Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas, although the state legislature has not repealed its sodomy laws that only apply to same-sex sexual acts. The state has prohibited discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in employment, housing and public accommodations since 2020. Proposed bills restricting preferred gender identity on legal documents, bans on transgender people in women's sports, bathroom use restrictions, among other bills were vetoed numerous times by Democratic Governor Laura Kelly since 2021. However, many of Kelly's vetoes were overridden by the Republican supermajority in the Kansas legislature and became law.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) rights in the U.S. state of Alaska have evolved significantly over the years. Since 1980, same-sex sexual conduct has been allowed, and same-sex couples can marry since October 2014. The state offers few legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, leaving LGBTQ people vulnerable to discrimination in housing and public accommodations; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. In addition, four Alaskan cities, Anchorage, Juneau, Sitka and Ketchikan, representing about 46% of the state population, have passed discrimination protections for housing and public accommodations.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people in the U.S. state of Mississippi face legal challenges and discrimination not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. LGBT rights in Mississippi are limited in comparison to other states. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Mississippi as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Lawrence v. Texas. Same-sex marriage has been recognized since June 2015 in accordance with the Supreme Court's decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. State statutes do not address discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBTQ people is illegal under federal law. The state capital Jackson and a number of other cities provide protections in housing and public accommodations as well.