Economics is the social science that studies how people interact with value; in particular, the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

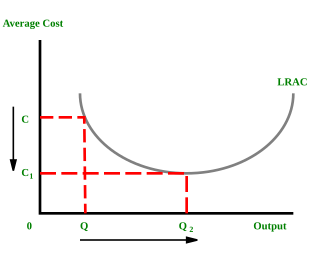

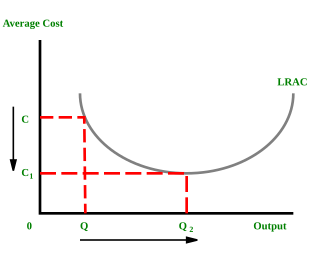

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, with cost per unit of output decreasing which causes scale increasing. At the basis of economies of scale there may be technical, statistical, organizational or related factors to the degree of market control.

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms.

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect market, also known as an atomistic market, is defined by several idealizing conditions, collectively called perfect competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for every product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current price. This equilibrium would be a Pareto optimum.

In economics, an externality is a cost or benefit that is imposed on a third party who did not agree to incur that cost or benefit. The concept of externality was first developed by economist Arthur Pigou in the 1920s. Air pollution from motor vehicles is an example of a negative externality. The costs of the air pollution for the rest of society is not compensated for by either the producers or users of motorized transport.

The law of comparative advantage describes how, under free trade, an agent will produce more of and consume less of a good for which they have a comparative advantage.

A price is the quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for one unit of goods or services. A price is influenced by production costs, supply of the desired item, and demand for the product. A price may be determined by a monopolist or may be imposed on the firm by market conditions.

In economics, marginal cost is the change in the total cost that arises when the quantity produced is incremented by one unit; that is, it is the cost of producing one more unit of a good. Intuitively, marginal cost at each level of production includes the cost of any additional inputs required to produce the next unit. At each level of production and time period being considered, marginal costs include all costs that vary with the level of production, whereas other costs that do not vary with production are fixed and thus have no marginal cost. For example, the marginal cost of producing an automobile will generally include the costs of labor and parts needed for the additional automobile but not the fixed costs of the factory that have already been incurred. In practice, marginal analysis is segregated into short and long-run cases, so that, over the long run, all costs become marginal. Where there are economies of scale, prices set at marginal cost will fail to cover total costs, thus requiring a subsidy. Marginal cost pricing is not a matter of merely lowering the general level of prices with the aid of a subsidy; with or without subsidy it calls for a drastic restructuring of pricing practices, with opportunities for very substantial improvements in efficiency at critical points.

A production–possibility frontier (PPF), production possibility curve (PPC), or production possibility boundary (PPB), or Transformation curve/boundary/frontier is a curve which shows various combinations of the amounts of two goods which can be produced within the given resources and technology/a graphical representation showing all the possible options of output for two products that can be produced using all factors of production, where the given resources are fully and efficiently utilized per unit time. A PPF illustrates several economic concepts, such as allocative efficiency, economies of scale, opportunity cost, productive efficiency, and scarcity of resources.

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being (welfare) at the aggregate (economy-wide) level.

The price elasticity of supply is a measure used in economics to show the responsiveness, or elasticity, of the quantity supplied of a good or service to a change in its price.

In economics, diminishing returns is the decrease in the marginal (incremental) output a production process as the amount of a single factor of production is incrementally increased, while the amounts of all other factors of production stay constant.

In economics, returns to scale describe what happens to long run returns as the scale of production increases, when all input levels including physical capital usage are variable. The concept of returns to scale arises in the context of a firm's production function. It explains the long run linkage of the rate of increase in output (production) relative to associated increases in the inputs. In the long run, all factors of production are variable and subject to change in response to a given increase in production scale. While economies of scale show the effect of an increased output level on unit costs, returns to scale focus only on the relation between input and output quantities.

In economics the long run is a theoretical concept in which all markets are in equilibrium, and all prices and quantities have fully adjusted and are in equilibrium. The long run contrasts with the short run, in which there are some constraints and markets are not fully in equilibrium.

In economics, partial equilibrium is a condition of economic equilibrium which takes into consideration only a part of the market to attain equilibrium.

In economics, supply is the amount of a resource that firms, producers, labourers, providers of financial assets, or other economic agents are willing and able to provide to the marketplace or directly to another agent in the marketplace. Supply can be in currency, time, raw materials, or any other scarce or valuable object that can be provided to another agent. This is often fairly abstract. For example in the case of time, supply is not transferred to one agent from another, but one agent may offer some other resource in exchange for the first spending time doing something. Supply is often plotted graphically as a supply curve, with the quantity provided plotted horizontally and the price plotted vertically.

In economics, a factor market is a market where factors of production are bought and sold.

In economics, factor payments are the income people receive for supplying the factors of production: land, labor, capital or entrepreneurship.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.