Benthos, also known as benthon, is the community of organisms that live on, in, or near the bottom of a sea, river, lake, or stream, also known as the benthic zone. This community lives in or near marine or freshwater sedimentary environments, from tidal pools along the foreshore, out to the continental shelf, and then down to the abyssal depths.

Oligochaeta is a subclass of animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadrile earthworms, and freshwater or semiterrestrial microdrile forms, including the tubificids, pot worms and ice worms (Enchytraeidae), blackworms (Lumbriculidae) and several interstitial marine worms.

Bioturbation is defined as the reworking of soils and sediments by animals or plants. It includes burrowing, ingestion, and defecation of sediment grains. Bioturbating activities have a profound effect on the environment and are thought to be a primary driver of biodiversity. The formal study of bioturbation began in the 1800s by Charles Darwin experimenting in his garden. The disruption of aquatic sediments and terrestrial soils through bioturbating activities provides significant ecosystem services. These include the alteration of nutrients in aquatic sediment and overlying water, shelter to other species in the form of burrows in terrestrial and water ecosystems, and soil production on land.

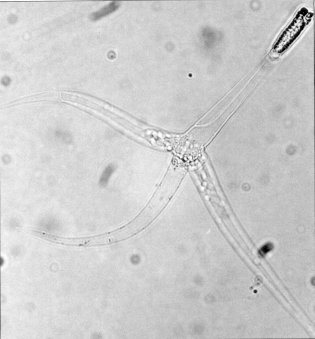

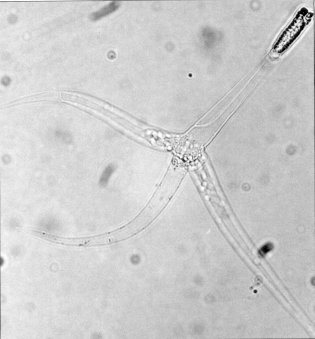

Myxobolus cerebralis is a myxosporean parasite of salmonids that causes whirling disease in farmed salmon and trout and also in wild fish populations. It was first described in rainbow trout in Germany in 1893, but its range has spread and it has appeared in most of Europe, the United States, South Africa, Canada and other countries from shipments of cultured and wild fish. In the 1980s, M. cerebralis was found to require a tubificid oligochaete to complete its life cycle. The parasite infects its hosts with its cells after piercing them with polar filaments ejected from nematocyst-like capsules. This infects the cartilage and possibly the nervous tissue of salmonids, causing a potentially lethal infection in which the host develops a black tail, spinal deformities, and possibly more deformities in the anterior part of the fish.

Tubifex tubifex, also called the sludge worm or sewage worm, is a species of tubificid segmented worm which inhabits the sediments of lakes and rivers on several continents. Tubifex probably includes several species, but distinguishing between them is difficult because the reproductive organs, commonly used in species identification, are resorbed after mating, and because the external characteristics of the worm vary with changes in salinity. These worms ingest sediments, selectively digest bacteria, and absorb molecules through their body walls. Micro-plastic ingestion by Tubifex worms acts as a significant risk for trophic transfer and biomagnification of microplastics up the aquatic food chain. The worms can survive with little oxygen by waving hemoglobin-rich tail ends to exploit all available oxygen, and can exchange carbon dioxide and oxygen through their thin skins, in a manner similar to frogs. They can also survive in areas heavily polluted with organic matter that almost no other species can endure. By forming a protective cyst and lowering its metabolic rate, T. tubifex can survive drought and food shortage. Encystment may also function in the dispersal of the worm. They usually inhabit the bottom sediments of lakes, rivers, and occasionally sewer lines and outlets.

The Naididae are a family of clitellate oligochaete worms like the sludge worm, Tubifex tubifex. They are key components of the benthic communities of many freshwater and marine ecosystems. In freshwater aquaria they may be referred to as detritus worms.

In oceanography and limnology, the sediment–water interface is the boundary between bed sediment and the overlying water column. The term usually refers to a thin layer of water at the very surface of sediments on the seafloor. In the ocean, estuaries, and lakes, this layer interacts with the water above it through physical flow and chemical reactions mediated by the micro-organisms, animals, and plants living at the bottom of the water body. The topography of this interface is often dynamic, as it is affected by physical processes and biological processes. Physical, biological, and chemical processes occur at the sediment-water interface as a result of a number of gradients such as chemical potential gradients, pore water gradients, and oxygen gradients.

The hyporheic zone is the region of sediment and porous space beneath and alongside a stream bed, where there is mixing of shallow groundwater and surface water. The flow dynamics and behavior in this zone is recognized to be important for surface water/groundwater interactions, as well as fish spawning, among other processes. As an innovative urban water management practice, the hyporheic zone can be designed by engineers and actively managed for improvements in both water quality and riparian habitat.

Eisenia fetida, known under various common names such as manure worm, redworm, brandling worm, panfish worm, trout worm, tiger worm, red wiggler worm, etc., is a species of earthworm adapted to decaying organic material. These worms thrive in rotting vegetation, compost, and manure. They are epigean, rarely found in soil. In this trait, they resemble Lumbricus rubellus.

Enchytraeidae is a family of microdrile oligochaetes. They resemble small earthworms and include both terrestrial species known as potworms that live in highly organic terrestrial environments, as well as some that are marine. The peculiar genus Mesenchytraeus is known as "ice worms", as they spend the majority of their lives within glaciers, only rising to the surface at certain points in the summer. Enchytraeidae also includes the Grindal Worm, which is commercially bred as aquarium fish food.

The Clitellata are a class of annelid worms, characterized by having a clitellum – the 'collar' that forms a reproductive cocoon during part of their life cycles. The clitellates comprise around 8,000 species. Unlike the class of Polychaeta, they do not have parapodia and their heads are less developed.

Tubifex is a cosmopolitan genus of tubificid annelids that inhabits the sediments of lakes, rivers and occasionally sewer lines. At least 13 species of Tubifex have been identified, with the exact number not certain, as the species are not easily distinguishable from each other.

Goussia is a taxonomic genus, first described in 1896 by Labbé, containing parasitic protists which largely target fish and amphibians as their hosts. Members of this genus are homoxenous and often reside in the gastrointestinal tract of the host, however others may be found in organs such as the gallbladder or liver. The genera Goussia, as current phylogenies indicate, is part of the class Conoidasida, which is a subset of the parasitic phylum Apicomplexa; features of this phylum, such as a distinct apical complex containing specialized secretory organelles, an apical polar ring, and a conoid are all present within Goussia, and assist in the mechanical invasion of host tissue. The name Goussia is derived from the French word gousse, meaning pod. This name is based on the bi-valve sporocyst morphology which some Goussians display. Of the original 8 classified Goussians, 6 fit the “pod” morphology. As of this writing, the genera consists of 59 individual species.

Olavius algarvensis is a species of gutless oligochaete worm in the family Tubificidae which depends on symbiotic bacteria for its nutrition.

The annelids, also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecologies – some in marine environments as distinct as tidal zones and hydrothermal vents, others in fresh water, and yet others in moist terrestrial environments.

Coralliodrilus rugosus is a species of clitellate oligochaete worm, first found in Belize, on the Caribbean side of Central America. It is found in a range of sediments near the limits of saline groundwater, but never below tidal zones.

Coralliodrilus randyi is a species of clitellate oligochaete worm, first found in Belize, on the Caribbean side of Central America.

Limnodriloides anxius is a species of clitellate oligochaete worm, first found in Belize, on the Caribbean side of Central America.

A glacier stream is a channelized area that is formed by a glacier in which liquid water accumulates and flows. Glacial streams are also commonly referred to as "glacier stream" or/and "glacial meltwater stream". The movement of the water is influenced and directed by gravity and the melting of ice. The melting of ice forms different types of glacial streams such as supraglacial, englacial, subglacial and proglacial streams. Water enters supraglacial streams that sit at the top of the glacier via filtering through snow in the accumulation zone and forming slush pools at the FIRN zone. The water accumulates on top of the glacier in supraglacial lakes and into supraglacial stream channels. The meltwater then flows through various different streams either entering inside the glacier into englacial channels or under the glacier into subglacial channels. Finally, the water leaves the glacier through proglacial streams or lakes. Proglacial streams do not only act as the terminus point but can also receive meltwater. Glacial streams can play a significant role in energy exchange and in the transport of meltwater and sediment.

Coralliodrilus is a genus of clitellate oligochaete worms.