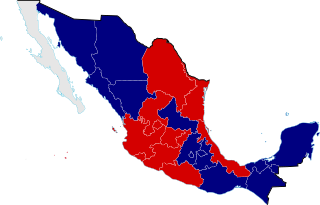

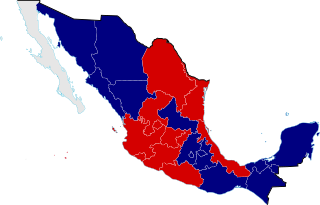

The United Mexican States is a federal republic composed of 32 federal entities: 31 states and Mexico City, an autonomous entity. According to the Constitution of 1917, the states of the federation are free and sovereign in all matters concerning their internal affairs. Each state has its own congress and constitution.

A constituent assembly is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected by popular vote, drawn by sortition, appointed, or some combination of these methods. Assemblies are typically considered distinct from a regular legislature, although members of the legislature may compose a significant number or all of its members. As the fundamental document constituting a state, a constitution cannot normally be modified or amended by the state's normal legislative procedures in some jurisdictions; instead a constitutional convention or a constituent assembly, the rules for which are normally laid down in the constitution, must be set up. A constituent assembly is usually set up for its specific purpose, which it carries out in a relatively short time, after which the assembly is dissolved. A constituent assembly is a form of representative democracy.

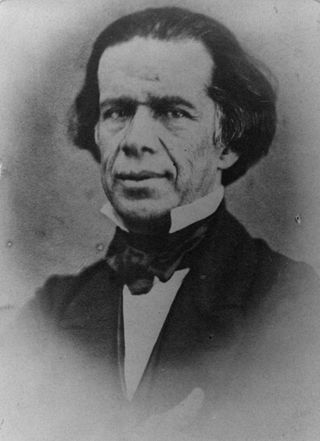

Ignacio Gregorio Comonfort de los Ríos, known as Ignacio Comonfort, was a Mexican politician and soldier who was also president during La Reforma.

The current Constitution of Mexico, formally the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States, was drafted in Santiago de Querétaro, in the State of Querétaro, Mexico, by a constituent convention during the Mexican Revolution. It was approved by the Constituent Congress on 5 February 1917, and was later amended several times. It is the successor to the Constitution of 1857, and earlier Mexican constitutions. "The Constitution of 1917 is the legal triumph of the Mexican Revolution. To some it is the revolution."

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1824 was the first constitution of Mexico, enacted on October 4 of 1824, inaugurating the First Mexican Republic.

Liberalism in Mexico was part of a broader nineteenth-century political trend affecting Western Europe and the Americas, including the United States, that challenged entrenched power. In Mexico, liberalism sought to make fundamental the equality of individuals before the law, rather than their benefiting from special privileges of corporate entities, especially the Roman Catholic Church, the military, and indigenous communities. Liberalism viewed universal, free, secular education as the means to transform Mexico's citizenry. Early nineteenth-century liberals promoted the idea of economic development in the overwhelmingly rural country where much land was owned by the Catholic Church and held in common by indigenous communities to create a large class of yeoman farmers. Liberals passed a series of individual Reform laws and then wrote a new constitution in 1857 to give full force to the changes. Liberalism in Mexico "was not only a political philosophy of republicanism but a package including democratic social values, free enterprise, a legal bundle of civil rights to protect individualism, and a group consciousness of nationalism." Mexican liberalism is most closely associated with anticlericalism. Mexican liberals looked to the U.S. as their model for development and actively sought the support of the U.S., while Mexican conservatives looked to Europe.

In the history of Mexico, La Reforma, or reform laws, refers to a pivotal set of laws, including a new constitution, that were enacted in the Second Federal Republic of Mexico during the 1850s after the Plan of Ayutla overthrew the dictatorship of Santa Anna. They were intended as modernizing measures: social, political, and economic, aimed at undermining the traditional power of the Catholic Church and the army. The reforms sought separation of church and state, equality before the law, and economic development. These anticlerical laws were enacted in the Second Mexican Republic between 1855 and 1863, during the governments of Juan Álvarez, Ignacio Comonfort and Benito Juárez. The laws also limited the ability of Catholic Church and indigenous communities from collectively holding land. The liberal government sought the revenues from the disentailment of church property, which could fund the civil war against Mexican conservatives and to broaden the base of property ownership in Mexico and encouraging private enterprise. Several of them were raised to constitutional status by the constituent Congress that drafted the liberal Constitution of 1857. Although the laws had a major impact on the Catholic Church in Mexico, liberal proponents were not opposed to the church as a spiritual institution, but rather sought a secular state and a society not dominated by religion.

The Reform War, or War of Reform, also known as the Three Years' War, and the Mexican Civil War, was a complex civil conflict in Mexico fought between Mexican liberals and conservatives with regional variations over the promulgation of Constitution of 1857. It has been called the "worst civil war to hit Mexico between the War of Independence of 1810-21 and the Revolution of 1910-20." Following the liberals' overthrow of the dictatorship of conservative Antonio López de Santa Anna, liberals passed a series of laws codifying their political program. These laws were incorporated into the new constitution. It aimed to limit the political power of the executive branch, as well as the political, economic, and cultural power of the Catholic Church. Specific measures were the expropriation of Church property; separation of church and state; reduction of the power of the Mexican Army by elimination of their special privileges; strengthening the secular state through public education; and measures to develop the nation economically.

Firearms regulation in Mexico is governed by legislation which sets the legality by which members of the armed forces, law enforcement and private citizens may acquire, own, possess and carry firearms; covering rights and limitations to individuals—including hunting and shooting sport participants, property and personal protection personnel such as bodyguards, security officers, private security, and extending to VIPs.

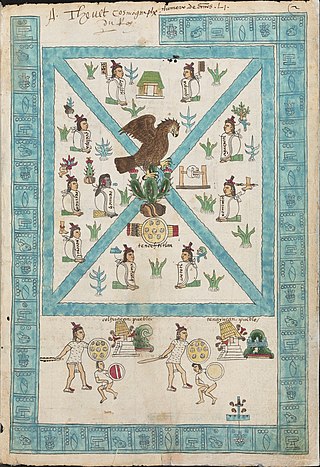

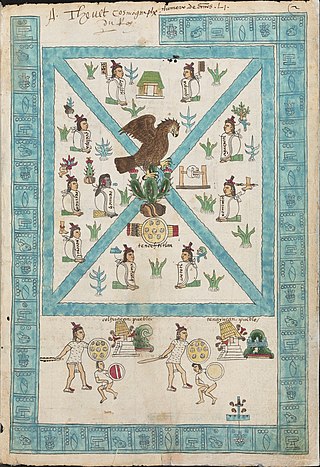

Several hypotheses seek to explain the etymology of Mexico which dates, at least, back to 14th century Mesoamerica. Among these are expressions in the Nahuatl language like "Place in the middle of the century plant" (Mexitli) and "Place in the Navel of the Moon" (Mēxihco), although there is still no consensus among experts.

The modern history of anticlericalism has often been characterized by deep conflicts between the government and the Catholic Church, sometimes including outright persecution of Catholics in Mexico.

Melchor Ocampo was a Mexican lawyer, scientist, and politician. A mestizo and a radical liberal, he was fiercely anticlerical, perhaps an atheist, and his early writings against the Catholic Church in Mexico gained him a reputation as a leading liberal thinker. Ocampo has been considered the heir to José María Luis Mora, the premier liberal intellectual of the early republic. He served in the administration of Benito Juárez and negotiated a controversial agreement with the United States, the McLane-Ocampo Treaty. The Mexican state where his hometown of Maravatío is located was later renamed Michoacán de Ocampo in his honor.

Nationality in Mexico is defined by multiple laws, including the 30th article of the Constitution of Mexico and other laws. The Constitution's 32nd article specifies the rights granted by Mexican legislation to Mexicans who also possess dual nationality. This article was written to establish the norms in this subject in order to avoid conflicts which may arise in the case of dual nationality. This law was last modified in 2021.

The history of the Catholic Church in Mexico dates from the period of the Spanish conquest (1519–21) and has continued as an institution in Mexico into the twenty-first century. Catholicism is one of many major legacies from the Spanish colonial era, the others include Spanish as the nation's language, the Civil Code and Spanish colonial architecture. The Catholic Church was a privileged institution until the mid nineteenth century. It was the sole permissible church in the colonial era and into the early Mexican Republic, following independence in 1821. Following independence, it involved itself directly in politics, including in matters that did not specifically involve the Church.

Irreligion in Mexico refers to atheism, deism, religious skepticism, secularism, and secular humanism in Mexican society, which was a confessional state after independence from Imperial Spain. The first political constitution of the Mexican United States, enacted in 1824, stipulated that Roman Catholicism was the national religion in perpetuity, and prohibited any other religion. Since 1857, however, by law, Mexico has had no official religion; as such, anti-clerical laws meant to promote a secular society, contained in the 1857 Constitution of Mexico and in the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, limited the participation in civil life of Roman Catholic organizations and allowed government intervention in religious participation in politics.

Anti-clericalism in Latin America sprang up in opposition to the power and influence of the Catholic Church in colonial and post-colonial Latin America.

The Catholic Church in Latin America began with the Spanish colonization of the Americas and continues up to the present day.

The Federal Constitution of the United Mexican States of 1857, often called simply the Constitution of 1857, was the liberal constitution promulgated in 1857 by Constituent Congress of Mexico during the presidency of Ignacio Comonfort. Ratified on February 5, 1857, the constitution established individual rights, including universal male suffrage, and others such as freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and the right to bear arms. It also reaffirmed the abolition of slavery, debtors' prisons, and all forms of cruel and unusual punishment such as the death penalty. The constitution was designed to guarantee a limited central government by federalism and created a strong national congress, an independent judiciary, and a small executive to prevent a dictatorship. Liberal ideals meant the constitution emphasized private property of individuals and sought to abolish common ownership by corporate entities, mainly the Catholic Church and indigenous communities, incorporating the legal thrust of the Lerdo Law into the constitution.

The Political Constitution of the State of Yucatán is the constitution which legally governs the free and sovereign state of Yucatán, one of 31 states with the Federal District comprise the 32 federative entities of the United Mexican States. It was drafted by the Constituent Congress of State, chaired by Héctor Victoria Aguilar in 1918 and promulgated by General Salvador Alvarado, pre-constitutional governor of Yucatán. The most important reforms were made in 1938, although its text has been revised and partially renovated over the 20th century and continues to be reformed so far.

Iamdudum is an encyclical of Pope Pius X, promulgated on May 24, 1911, which condemned Portuguese anticlericals for their deprivation of religious civil liberties in the wake of the 5 October 1910 revolution and the "incredible series of excesses and crimes which has been enacted in Portugal for the oppression of the Church."