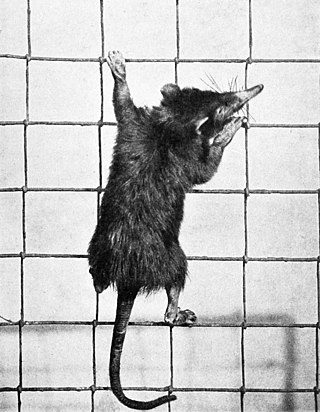

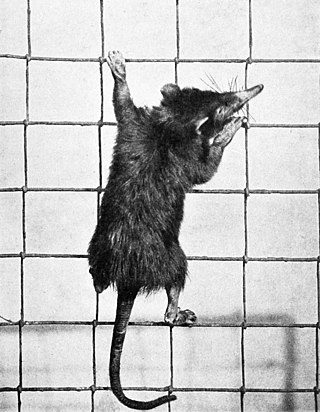

The Cuban solenodon or almiquí is a small, furry, shrew-like mammal endemic to mountainous forests on Cuba. It is the only species in the genus Atopogale. An elusive animal, it lives in burrows and is only active at night when it uses its unusual toxic saliva to feed on insects. The solenodons, native to the Caribbean, are one of only a few mammals that are venomous.

Solenodons are venomous, nocturnal, burrowing, insectivorous mammals belonging to the family Solenodontidae. The two living solenodon species are the Cuban solenodon and the Hispaniolan solenodon. Threats to both species include habitat destruction and predation by non-native cats, dogs, and mongooses, introduced by humans to the solenodons' home islands to control snakes and rodents.

Pico Duarte is the highest peak in the Dominican Republic, on the island of Hispaniola and in all the Caribbean. At 3,101 m (10,174 ft) above sea level, it gives Hispaniola the 16th-highest maximum elevation of any island in the world. Additionally, it is only 85 kilometres northeast of the region's lowest point, Lake Enriquillo, 46 m below sea level. It is part of the Cordillera Central range, which extends from the plains between San Cristóbal and Baní to the northwestern peninsula of Haiti, where it is known as the Massif du Nord. The highest elevations of the Cordillera Central are found in the Pico Duarte and Valle Nuevo massifs.

The Puerto Rican nesophontes, or Puerto Rican shrew, is an extinct eulipotyphlan endemic to Puerto Rico.

Nesophontes, sometimes called West Indies shrews, is the sole genus of the extinct, monotypic mammal family Nesophontidae in the order Eulipotyphla. These animals were small insectivores, about 5 to 15 cm long, with a long slender snout and head and a long tail. They were endemic to the Greater Antilles, in Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, the United States Virgin Islands, and the Cayman Islands.

The fauna of Puerto Rico is similar to other island archipelago faunas, with high endemism, and low, skewed taxonomic diversity. Bats are the only extant native terrestrial mammals in Puerto Rico. All other terrestrial mammals in the area were introduced by humans, and include species such as cats, goats, sheep, the small Indian mongoose, and escaped monkeys. Marine mammals include dolphins, manatees, and whales. Of the 349 bird species, about 120 breed in the archipelago, and 47.5% are accidental or rare.

The Hispaniolan solenodon, also known as the agouta, is a small, furry, shrew-like mammal endemic to the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. Like other solenodons, it is a venomous, insect-eating animal that lives in burrows and is active at night. It is an elusive animal and was only first described in 1833; its numbers are stable in protected forests but it remains the focus of conservation efforts.

Acratocnus is an extinct genus of Caribbean sloths that were found on Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico during the Late Pleistocene and early-mid Holocene.

The Atalaye nesophontes is an extinct species of mammal in the family Nesophontidae. It was endemic to Hispaniola in the Caribbean, and is only known from fossil deposits.

The St. Michel nesophontes is an extinct species of mammal in the family Nesophontidae. It was endemic to Hispaniola.

Marcano's solenodon is an extinct species of mammal in the family Solenodontidae known only from skeletal remains found on the island of Hispaniola.

The Caribbean bioregion is a biogeographic region that includes the islands of the Caribbean Sea and nearby Atlantic islands, which share a fauna, flora and mycobiota distinct from surrounding bioregions.

The mammalian order Pilosa, which includes the sloths and anteaters, includes various species from the Caribbean region. Many species of sloths are known from the Greater Antilles, all of which became extinct over the last millennia, but some sloths and anteaters survive on islands closer to the mainland.

A unique and diverse albeit phylogenetically restricted mammal fauna is known from the Caribbean region. The region—specifically, all islands in the Caribbean Sea and the Bahamas, Turks and Caicos Islands, and Barbados, which are not in the Caribbean Sea but biogeographically belong to the same Caribbean bioregion—has been home to several families found nowhere else, but much of this diversity is now extinct.

Megalocnidae is an extinct family of sloths, native to the islands of the Greater Antilles from the Early Oligocene to the Mid-Holocene. They are known from Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, but are absent from Jamaica. While they were formerly placed in the Megalonychidae alongside two-toed sloths and ground sloths like Megalonyx, recent mitochondrial DNA and collagen sequencing studies place them as the earliest diverging group basal to all other sloths. or as an outgroup to Megatherioidea. They displayed significant diversity in body size and lifestyle, with Megalocnus being terrestrial and probably weighing several hundred kilograms, while Neocnus was likely arboreal and similar in weight to extant tree sloths, at less than 10 kilograms.

The Cayman nesophontes is an extinct eulipotyphlan of the genus Nesophontes that was once endemic to the Cayman Islands ; the animal lived in the island montane forest/brush endemic to the Cayman Islands and was an insectivore. It is known from subfossil remains, that bear bite marks attributed to crocodiles, collected from caves, sinkholes and peat deposits on the Islands between the 1930s and the 1990s. It was named in 2019.