Persians are an Iranic ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

Hormizd-Ardashir, better known by his dynastic name of Hormizd I, was the third Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) of Iran, who ruled from May 270 to June 271. He was the third-born son of Shapur I, under whom he was governor-king of Armenia, and also took part in his father's wars against the Roman Empire. Hormizd I's brief time as ruler of Iran was largely uneventful. He built the city of Hormizd-Ardashir, which remains a major city today in Iran. He promoted the Zoroastrian priest Kartir to the rank of chief priest (mowbed) and gave the Manichaean prophet Mani permission to continue his preaching.

Hormizd II was king (shah) of the Sasanian Empire. He ruled for six years and five months, from 303 to 309. He was a son and successor of Narseh.

The Safavid dynasty was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the Persian Empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam. The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Iranian Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin, but during their rule they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries, nevertheless, for practical purposes, they were Turkish-speaking and Turkified. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

Ismail I was the founder and first shah of Safavid Iran, ruling from 1501 until his death in 1524. His reign is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The rule of Ismail I is one of the most vital in the history of Iran. Before his accession in 1501, Iran, since its Islamic conquest eight-and-a-half centuries earlier, had not existed as a unified country under native Iranian rule. Although many Iranian dynasties rose to power amidst this whole period, it was only under the Buyids that a vast part of Iran properly returned to Iranian rule (945–1055).

Sistān, also known as Sakastān and Sijistan, is a historical region in present-day south-eastern Iran, south-western Afghanistan and extending across the borders of south-western Pakistan. Mostly corresponding to the then Achaemenid region of Drangiana and extending southwards of the Helmand River not far off from the city of Alexandria in Arachosia. Largely desert, the region is bisected by the Helmand River, the largest river in Afghanistan, which empties into the Hamun Lake that forms part of the border between Iran and Afghanistan.

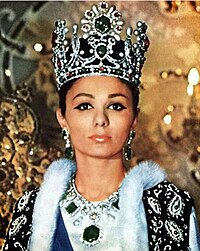

Azarmidokht was Sasanian queen (banbishn) of Iran from 630 to 631. She was the daughter of king (shah) Khosrow II. She was the second Sasanian queen; her sister Boran ruled before and after her. Azarmidokht came to power in Iran after her cousin Shapur-i Shahrvaraz was deposed by the Parsig faction, led by Piruz Khosrow, who helped Azarmidokht ascend the throne. Her rule was marked by an attempt of a nobleman and commander Farrukh Hormizd to marry her and come to power. After the queen's refusal, he declared himself an anti-king. Azarmidokht had him killed as a result of a successful plot. She was, however, killed herself shortly afterwards by Rostam Farrokhzad in retaliation for his father's death. She was succeeded by Boran.

The page details the timeline of History of Iran.

The House of Karen, also known as Karen-Pahlav, was one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran during the rule of Parthian and Sassanian Empires. The seat of the dynasty was at Nahavand, about 65 km south of Ecbatana. Members of the House of Karen were of notable rank in the administrative structure of the Sassanian empire in multiple periods of its four century-long history.

Abu Ali Muhammad Bal'ami, also called Amirak Bal'ami and Bal'ami-i Kuchak, was a 10th-century Persian historian, writer, and vizier to the Samanids. He was from the influential Bal'ami family.

The Ottoman–Persian War of 1775–1776 was fought between the Ottoman Empire and the Zand dynasty of Persia. The Persians, ruled by Karim Khan and led by his brother Sadeq Khan Zand, invaded southern Iraq and after besieging Basra for a year, took the city from the Ottomans in 1776. The Ottomans, unable to send troops, were dependent on the Mamluk governors to defend that region.

The Kar-Kiya dynasty, also known as the Kiya'ids, was a local Zaydi dynasty which mainly ruled over Biya-pish from the 1370s to 1592.

Farrukh Hormizd or Farrokh Hormizd, also known as Hormizd V, was an Iranian prince, who was one of the leading figures in Sasanian Iran in the early 7th-century. He served as the military commander (spahbed) of northern Iran. He later came in conflict with the Iranian nobility, "dividing the resources of the country". He was later killed by Siyavakhsh in a palace plot on the orders of Azarmidokht after he proposed to her in an attempt to usurp the Sasanian throne. He had two children, Rostam Farrokhzad and Farrukhzad.

Allahverdi Khan was a Safavid military officer of Armenian origin. He was the son of a certain Khosrow Khan, and had a brother named Emamverdi Beg.

Salman Khan Ustajlu was a Turkoman military leader from the Ustajlu tribe, who became a powerful and rich figure during his service in Safavid Iran. He briefly served as the grand vizier of the Safavid king (shah) Abbas I from 1621 until his death in 1623/4. He was succeeded by Khalifeh Sultan.

Pars was a Sasanian province in Late Antiquity, which almost corresponded to the present-day province of Fars. The province bordered Khuzestan in the west, Kirman in the east, Spahan in the north, and Mazun in the south.

Kirman was a Sasanian province in Late Antiquity, which almost corresponded to the present-day province of Kerman. The province bordered Pars in the west, Abarshahr and Sakastan in the northeast, Paradan in the east, Spahan in the north, and Mazun in the south. The capital of the province was Shiragan.

The Khalifeh family, also known as the Khalifeh sayyids, were a branch of the Marashi dynasty of Mazandaran, whose ancestor, Amir Nezam al-Din, had settled in the Golbar quarter of Isfahan in the 15th century.

Mirza Mohammad Mahdi Karaki was an Iranian cleric and statesman, who served as the grand Vizier of the Safavid king (shah) Abbas II, and the latter's son and successor Suleiman I. He was the son of Mirza Habibollah Karaki, who served as the sadr-i mamalik from 1632/3 till his death 1650.