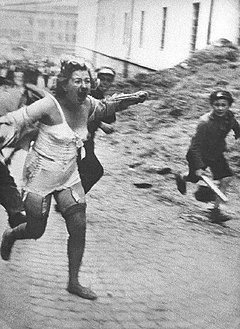

Woman chased by men and youth armed with clubs, Medova Street in Lviv, 1941 | |

| Date | June 1941 - July 1941 |

|---|---|

| Location | Lviv, Occupied Poland (Nazi German Distrikt Galizien ) |

| Coordinates | 49°30′36″N24°00′36″E / 49.510°N 24.010°E Coordinates: 49°30′36″N24°00′36″E / 49.510°N 24.010°E |

| Type | Killings |

| Participants | Germans, Local crowds, Ukrainian nationalists |

| Deaths | In excess of 6,000 Jews [1] |

The Lviv pogroms were the consecutive massacres of Jews living in the city of Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), perpetrated by the German commandos and the Ukrainian nationalists from 30 June to 2 July 1941, and from 25 to 29 July 1941, during the Wehrmacht's attack on the Soviet positions in occupied eastern Poland in World War II. [2] Historian Peter Longerich and the Holocaust Encyclopedia estimate that the first pogrom cost at least 4,000 lives. [1] It was followed by the additional 2,500 to 3,000 arrests and executions in subsequent Einsatzgruppe killings, [3] and culminated in the so-called "Petlura Days" massacre of more than 2,000 Jews, all killed in a one-month span. [1] [4]

A massacre is a killing, typically of multiple victims, considered morally unacceptable, especially when perpetrated by a group of political actors against defenseless victims. The word is a loan of a French term for "butchery" or "carnage".

Lwów Voivodeship was an administrative unit of interwar Poland (1918–1939). Because of the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland in accordance with the secret Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, it became occupied by both the Wehrmacht and the Red Army in September 1939. Following the conquest of Poland however, the Polish underground administration existed there until August 1944. The Voivodeship was not returned to Poland after the war ended. It was split diagonally just east of Przemyśl; with its eastern half ceded to the Ukrainian SSR at the insistence of Joseph Stalin during the Tehran Conference confirmed at the Yalta Conference of 1945.

Lviv is the largest city in western Ukraine and the seventh-largest city in the country overall, with a population of around 728,350 as of 2016. Lviv is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine.

Contents

- First pogrom

- Killings by Einsatzgruppe

- Petlura days

- Aftermath

- Controversy

- See also

- References

- External links

Prior to the 1939 invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and the ensuing Holocaust in Europe, the city of Lviv had the third-largest Jewish population in Poland during the interwar period, which swelled further to over 200,000 Jews as the refugees fled east from the Nazis. [5] Right after the conquest of Poland, on 28 September 1939, the USSR and Germany signed a frontier treaty assigning about 200,000 km² of land inhabited by 13.5 million people of all nationalities to the Soviet Union. Lviv remained in the Soviet zone of occupation for two years. [6] Of the estimated total of 20,000–30,000 former citizens of Poland executed by the Soviet NKVD as "enemies of the people," [7] nearly 9,000 were murdered in the newly-acquired western Ukraine. [8] Sovietization policies in Polish lands – cordoned off from the rest of the USSR – included confiscation of property and mass deportations of the hundreds of thousands of local citizens to Siberia. [9] On Sunday, 22 June 1941 Germany attacked the Soviet Union.

The Invasion of Poland, known in Poland as the September Campaign or the 1939 Defensive War, and in Germany as the Poland Campaign (Polenfeldzug), was an invasion of Poland by Germany that marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviets invaded Poland on 17 September following the Molotov–Tōgō agreement that terminated the Soviet and Japanese Battles of Khalkhin Gol in the east on 16 September. The campaign ended on 6 October with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland under the terms of the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty.

The Soviet invasion of Poland was a military operation by the Soviet Union without a formal declaration of war. On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, sixteen days after Germany invaded Poland from the west. Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by Germany and the Soviet Union. The Soviet invasion of Poland was secretly approved by Germany following the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact on 23 August 1939.

In the context of the history of the 20th century, the interwar period was the period between the end of the First World War in November 1918 and the beginning of the Second World War in September 1939.