Alexios I Komnenos, Latinized as Alexius I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Inheriting a collapsing empire and faced with constant warfare during his reign, Alexios was able to curb the Byzantine decline and begin the military, financial, and territorial recovery known as the Komnenian restoration. His appeals to Western Europe for help against the Seljuk Turks were the catalyst that sparked the First Crusade. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during his reign that the Komnenos family came to full power and initiated a hereditary succession to the throne.

Romanos III Argyros, or Argyropoulos was Byzantine Emperor from 1028 until his death. He was a Byzantine noble and senior official in Constantinople when the dying Constantine VIII forced him to divorce his wife and marry the emperor's daughter Zoë. Upon Constantine's death three days later, Romanos took the throne.

Theodora Porphyrogenita was Byzantine Empress from 21 April 1042 to her death on 31 August 1056, and sole ruler from 11 January 1055. She was the last sovereign of the Macedonian dynasty, that ruled the Byzantine Empire for almost 200 years.

Michael V Kalaphates was Byzantine emperor for four months in 1041–1042. He was the nephew and successor of Michael IV and the adoptive son of Michael IV's wife Empress Zoe. He was popularly called "the Caulker" (Kalaphates) in accordance with his father's original occupation.

Michael VII Doukas or Ducas, nicknamed Parapinakes, was the senior Byzantine emperor from 1071 to 1078. He was known as incompetent as an emperor and reliant on court officials, especially of his finance minister Nikephoritzes, who increased taxation and luxury spending while not properly financing their army. Under his reign, Bari was lost and his empire faced open revolt in the Balkans. Along with the advancing Seljuk Turks in the eastern front, Michael also had to contend with his mercenaries openly turning against the empire. Michael stepped down as emperor in 1078 and later retired to a monastery.

Zoe Porphyrogenita was a member of the Macedonian dynasty who briefly reigned as Byzantine empress in 1042, alongside her sister Theodora. Before that she was enthroned as empress consort or empress mother to a series of co-rulers, two of whom were married to her.

Leo VI, also known as Leothe Wise, was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty, he was very well read, leading to his epithet. During his reign, the renaissance of letters, begun by his predecessor Basil I, continued; but the empire also saw several military defeats in the Balkans against Bulgaria and against the Arabs in Sicily and the Aegean. His reign also witnessed the formal discontinuation of several ancient Roman institutions, such as the separate office of Roman consul.

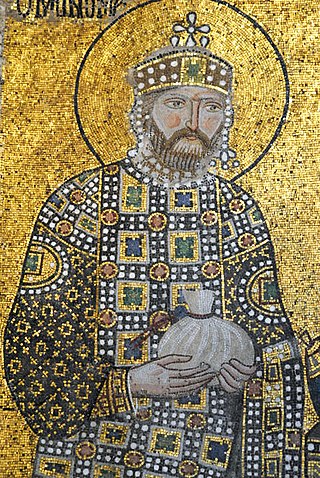

Constantine IX Monomachos reigned as Byzantine emperor from June 1042 to January 1055. Empress Zoë Porphyrogenita chose him as a husband and co-emperor in 1042, although he had been exiled for conspiring against her previous husband, Emperor Michael IV the Paphlagonian. The couple shared the throne with Zoë's sister Theodora Porphyrogenita. Zoë died in 1050, and Constantine continued his collaboration with Theodora until his own death five years later.

The Macedonian dynasty ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, following the Amorian dynasty. During this period, the Byzantine state reached its greatest extent since the Early Muslim conquests, and the Macedonian Renaissance in letters and arts began. The dynasty was named after its founder, Basil I the Macedonian who came from the theme of Macedonia.

John the Orphanotrophos was the chief court eunuch (parakoimomenos) during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Romanos III. John was born in the region of Paphlagonia. His family were said to be involved in a disreputable trade, perhaps money changing or, according to George Kedrenos, counterfeiting. John was the eldest of five brothers. Two, Constantine and George, were also eunuchs, while the other two, Niketas and Michael, were 'bearded' men; the latter became Michael IV the Paphlagonian after John introduced him to the reigning Empress Zoë. According to Michael Psellos, the two became lovers and may have plotted to assassinate Zoë's husband. Romanos was probably killed in his bath on 11 April 1034. Some contemporary sources implicate John in the assassination.

Michael Dokeianos, erroneously called Doukeianos by some modern writers, was a Byzantine nobleman and military leader, who married into the Komnenos family. He was active in Sicily under George Maniakes before going to Southern Italy as Catepan of Italy in 1040–41. He was recalled after being twice defeated in battle during the Lombard-Norman revolt of 1041, a decisive moment in the eventual Norman conquest of southern Italy. He is next recorded in 1050, fighting against a Pecheneg raid in Thrace. He was captured during battle but managed to maim the Pecheneg leader, after which he was put to death and mutilated.

Alusian was a Bulgarian and Byzantine noble who ruled as emperor (tsar) of Bulgaria for a short time in 1041.

John Doukas was the son of Andronikos Doukas, a Paphlagonian Greek nobleman who may have served as governor of the theme of Bulgaria (Moesia), and the younger brother of Emperor Constantine X Doukas. John Doukas was the paternal grandfather of Irene Doukaina, wife of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos.

The Uprising of Petar Delyan, which took place in 1040–1041, was a major Bulgarian rebellion against the Byzantine Empire in the Theme of Bulgaria. It was the largest and best-organised attempt to restore the former Bulgarian Empire until the rebellion of Ivan Asen I and Petar IV in 1185.

Nikephoros Bryennios the Elder, Latinized as Nicephorus Bryennius, was a Byzantine Greek general who tried to establish himself as Emperor in the late eleventh century. His contemporaries considered him the best tactician in the empire.

Nikephoros Bryennios, Latinized as Nicephorus Bryennius, was an important Byzantine general who was involved in rebellions against the empress Theodora and later the emperor Michael VI Stratiotikos.

Constantine Dalassenos was a prominent Byzantine aristocrat of the first half of the 11th century. An experienced and popular general, he came close to ascending the imperial throne by marriage to the porphyrogenita Empress Zoe in 1028. He accompanied the man Zoe did marry, Emperor Romanos III Argyros, on campaign and was blamed by some chroniclers for Romanos' humiliating defeat at the Battle of Azaz.

Petar Delyan, sometimes enumerated as Petar II, was the leader of a major Bulgarian uprising against Byzantine rule in the Theme of Bulgaria during the summer of 1040. He was proclaimed Tsar of Bulgaria, as Samuel's grandson in Belgrade, then in the theme of Bulgaria. His original name may have been simply Delyan, in which case he assumed the name Petar II upon accession, commemorating the sainted Emperor Petar I, who had died in 970. The exact year of his birth cannot be ascertained with certainty, but it is believed to have taken place during the early 11th century, likely between 1000 and 1014. Similarly, the year of his death is estimated to be 1041.