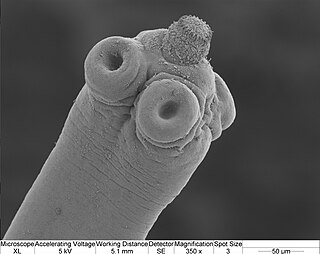

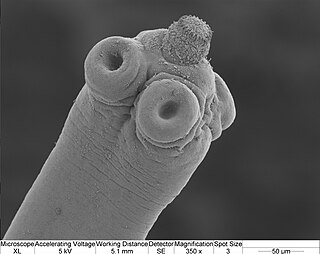

Acanthocephala is a phylum of parasitic worms known as acanthocephalans, thorny-headed worms, or spiny-headed worms, characterized by the presence of an eversible proboscis, armed with spines, which it uses to pierce and hold the gut wall of its host. Acanthocephalans have complex life cycles, involving at least two hosts, which may include invertebrates, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals. About 1420 species have been described.

Hymenolepiasis is infestation by one of two species of tapeworm: Hymenolepis nana or H. diminuta. Alternative names are dwarf tapeworm infection and rat tapeworm infection. The disease is a type of helminthiasis which is classified as a neglected tropical disease.

Gnathostomiasis is the human infection caused by the nematode (roundworm) Gnathostoma spinigerum and/or Gnathostoma hispidum, which infects vertebrates.

Echinococcus multilocularis is a small cyclophyllid tapeworm found extensively in the northern hemisphere. E. multilocularis, along with other members of the Echinococcus genus, produce diseases known as echinococcosis. Unlike E. granulosus,E. multilocularis produces many small cysts that spread throughout the internal organs of the infected animal. The resultant disease is called Alveolar echinococcosis, and is caused by ingesting the eggs of E. multilocularis.

Hymenolepis diminuta, also known as rat tapeworm, is a species of Hymenolepis tapeworm that causes hymenolepiasis. It has slightly bigger eggs and proglottids than H. nana and infects mammals using insects as intermediate hosts. The adult structure is 20 to 60 cm long and the mature proglottid is similar to that of H. nana, except it is larger.

Mammomonogamus is a genus of parasitic nematodes of the family Syngamidae that parasitise the respiratory tracts of cattle, sheep, goats, deer, cats, orangutans, and elephants. The nematodes can also infect humans and cause the disease called mammomonogamiasis. Several known species fall under the genus Mammomonogamus, but the most common species found to infest humans is M. laryngeus. Infection in humans is very rare, with only about 100 reported cases worldwide, and is assumed to be largely accidental. Cases have been reported from the Caribbean, China, Korea, Thailand, and Philippines.

Pomphorhynchus laevis is an endo-parasitic acanthocephalan worm, with a complex life cycle, that can modify the behaviour of its intermediate host, the freshwater amphipod Gammarus pulex. P. laevis does not contain a digestive tract and relies on the nutrients provided by its host species. In the fish host this can lead to the accumulation of lead in P. laevis by feeding on the bile of the host species.

Hymenolepis is a genus of cyclophyllid tapeworms responsible for hymenolepiasis. They are parasites of humans and other mammals. The focus in this article is in Hymenolepis commonly parasitizing humans.

Gongylonema pulchrum is the only parasite of the genus Gongylonema capable of infecting humans.

Nanophyetus salmincola is a food-borne intestinal trematode parasite prevalent on the Pacific Northwest coast. The species may be the most common trematode endemic to the United States.

Profilicollis is a genus of acanthocephalan parasites of crustaceans. The status of the genus Profilicollis has been debated, and species placed in this genus were formerly included in the genus Polymorphus. However, research on the morphology of the group and their use of hosts has concluded that Profilicollis and Polymorphus should be regarded as distinct genera, and species previously described as Polymorphus altmani are now referred to as Profilicollis altmani in taxonomic and biological literature. Profilicollis parasites infect decapod crustaceans, usually shore crabs, as intermediate hosts, and use many species of shorebirds as definitive (final) hosts.

Angiostrongylus costaricensis is a species of parasitic nematode and is the causative agent of abdominal angiostrongyliasis in humans. It occurs in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Gigantorhynchus is a genus of Acanthocephala that parasitize marsupials, anteaters, and possibly baboons by attaching themselves to the intestines using their hook-covered proboscis. Their life cycle includes an egg stage found in host feces, a cystacanth (larval) stage in an intermediate host such as termites, and an adult stage where cystacanths mature in the intestines of the host. This genus is characterized by a cylindrical proboscis with a crown of robust hooks at the apex followed by numerous small hooks on the rest of the proboscis, a long body with pseudosegmentation, filiform lemnisci, and ellipsoid testes. The largest known specimen is the female G. ortizi with a length of around 240 millimetres (9.4 in) and a width of 2 millimetres (0.08 in). Genetic analysis on one species of Gigantorhynchus places it with the related genus Mediorhynchus in the family Gigantorhynchidae. Six species in this genus are distributed across Central and South America and possibly Zimbabwe. Infestation by a Gigantorhynchus species may cause partial obstructions of the intestines, severe lesions of the intestinal wall, and may lead to death.

Mediorhynchus is a genus of small parasitic spiny-headed worms. Phylogenetic analysis has been conducted on two known species of Mediorhynchus and confirmed the placement along with the related genus Gigantorhynchus in the family Gigantorhynchida. The distinguishing features of this order among archiacanthocephalans is a divided proboscis. This genus contains fifty-eight species that are distributed globally. These worms exclusively parasitize birds by attaching themselves around the cloaca using their hook-covered proboscis. The bird hosts are of different orders.

Moniliformidae is a family of parasitic spiny-headed worms. It is the only family in the Moniliformida order and contains three genera: Australiformis containing a single species, Moniliformis containing eighteen species and Promoniliformis containing a single species. Genetic analysis have determined that the clade is monophyletic despite being distributed globally. These worms primarily parasitize mammals, including humans in the case of Moniliformis moniliformis, and occasionally birds by attaching themselves into the intestinal wall using their hook-covered proboscis. The intermediate hosts are mostly cockroaches. The distinguishing features of this order among archiacanthocephalans is the presence of a cylindrical proboscis with long rows of hooks with posteriorly directed roots and proboscis retractor muscles that pierce both the posterior and ventral end or just posterior end of the receptacle. Infestation with Monoliformida species can cause moniliformiasis, an intestinal condition characterized as causing lesions, intestinal distension, perforated ulcers, enteritis, gastritis, crypt hypertrophy, goblet cell hyperplasia, and blockages.

Oligacanthorhynchida is an order containing a single parasitic worm family, Oligacanthorhynchidae, that attach themselves to the intestinal wall of terrestrial vertebrates.

Hymenolepis microstoma, also known as the rodent tapeworm, is an intestinal dwelling parasite. Adult worms live in the bile duct and small intestines of mice and rats, and larvae metamorphose in the haemocoel of beetles. It belongs to the genus Hymenolepis; tapeworms that cause hymenolepiasis. H. microstoma is prevalent in rodents worldwide, but rarely infects humans.

Alaria americana is a species of a trematode in a family Diplostomidae. All of these species infect carnivorous mammals by living in their small intestines as mature worms. A. americana are most frequently found in temperate regions, predominately in northern North America. This organisms habit is extremely diverse, as it occupies four different hosts throughout its lifetime. This trematode thrives in areas close to water as it is needed for several developmental stages to occur. A. americana has been isolated to the different North American mammals with a wide range of definitive hosts, including cattle, lynx, martens, skunks, bobcats, foxes, coyotes, and wolves.

Corynosoma autrale is a species of acanthocephalan. This species usually infects pinnipeds; the semi-aquatic fin-footed marine mammals most commonly known as seals and sea lions. Pinniped infections are not exclusive, recently C. australe has been discovered in Magellanic penguins.

Pachysentis is a genus of Acanthocephala that parasitize carnivourous mammals by attaching themselves to the intestines using their hook-covered proboscis. Their life cycle includes an egg stage found in host feces, a cystacanth (larval) stage in an intermediate host such as the Egyptian cobra, and an adult stage where cystacanths mature in the intestines of the host. This genus appears identical to the closely related Oncicola apart from a greater number of hooks on the proboscis. The eleven species in this genus are distributed across Africa and the Americas.