Meeker is the Statutory Town in and the county seat of Rio Blanco County, Colorado, United States, that is the most populous municipality in the county. The town population was 2,374 at the 2020 United States Census.

Ouray was a Native American chief of the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) band of the Ute tribe, then located in western Colorado. Because of his leadership ability, Ouray was acknowledged by the United States government as a chief of the Ute and he traveled to Washington, D.C. to negotiate for the welfare of the Utes. Raised in the culturally diverse town of Taos, Ouray learned to speak many languages that helped him in the negotiations, which were complicated by the manipulation of his grief over his five-year-old son abducted during an attack by the Sioux. Ouray met with Presidents Lincoln, Grant, and Hayes and was called the man of peace because he sought to make treaties with settlers and the government.

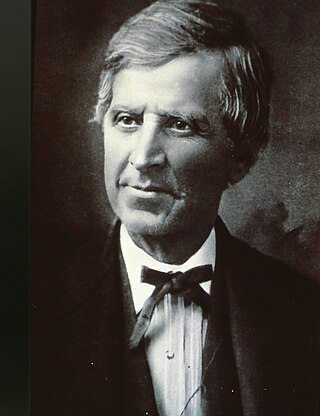

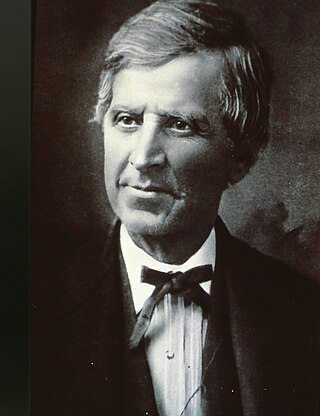

Nathan Cook Meeker was a 19th-century American journalist, homesteader, entrepreneur, and Indian agent for the federal government. He is noted for his founding in 1870 of the Union Colony, a cooperative agricultural colony in present-day Greeley, Colorado.

Ute are the Indigenous people of the Ute tribe and culture among the Indigenous peoples of the Great Basin. They had lived in sovereignty in the regions of present-day Utah and Colorado.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is one of three federally recognized tribes of the Ute Nation, and are mostly descendants of the historic Weeminuche Band who moved to the Southern Ute reservation in 1897. Their reservation is headquartered at Towaoc, Colorado on the Ute Mountain Ute Indian Reservation in southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico and small sections of Utah.

Meeker Massacre, or Meeker Incident, White River War, Ute War, or the Ute Campaign), took place on September 29, 1879 in Colorado. Members of a band of Ute Indians attacked the Indian agency on their reservation, killing the Indian agent Nathan Meeker and his 10 male employees and taking five women and children as hostages. Meeker had been attempting to convert the Utes to Christianity, to make them farmers, and to prevent them from following their nomadic culture. On the same day as the massacre, United States Army forces were en route to the Agency from Fort Steele in Wyoming due to threats against Meeker. The Utes attacked U.S. troops led by Major Thomas T. Thornburgh at Milk Creek, 18 mi (29 km) north of present day Meeker, Colorado. They killed the major and 13 troops. Relief troops were called in and the Utes dispersed.

The Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation is located in northeastern Utah, United States. It is the homeland of the Ute Indian Tribe, and is the largest of three Indian reservations inhabited by members of the Ute Tribe of Native Americans.

The Uinta Basin is a physiographic section of the larger Colorado Plateaus province, which in turn is part of the larger Intermontane Plateaus physiographic division. It is also a geologic structural basin in eastern Utah, east of the Wasatch Mountains and south of the Uinta Mountains. The Uinta Basin is fed by creeks and rivers flowing south from the Uinta Mountains. Many of the principal rivers flow into the Duchesne River which feeds the Green River—a tributary of the Colorado River. The Uinta Mountains form the northern border of the Uinta Basin. They contain the highest point in Utah, Kings Peak, with a summit 13,528 feet above sea level. The climate of the Uinta Basin is semi-arid, with occasionally severe winter cold.

The Ute Indian Tribe of the Uinta and Ouray Reservation is a Federally Recognized Tribe of Indians in northeastern Utah, United States. Three bands of Utes comprise the Ute Indian Tribe: the Whiteriver Band, the Uncompahgre Band and the Uintah Band. The Tribe has a membership of more than three thousand individuals, with over half living on the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation. The Ute Indian Tribe operates its own tribal government and oversees approximately 1.3 million acres of trust land which contains significant oil and gas deposits.

The Timpanogos are a tribe of Native Americans who inhabited a large part of central Utah, in particular, the area from Utah Lake east to the Uinta Mountains and south into present-day Sanpete County.

White River Utes are a Native American band, made of two earlier bands, the Yampa from the Yampa River Valley and the Parianuche Utes who lived along the Grand Valley in Colorado and Utah.

Josephine Meeker, was a teacher and physician at the White River Indian Agency in Colorado Territory, where her father Nathan Meeker was the United States (US) agent. On September 29, 1879, he and 10 of his male employees were killed in a Ute attack, in what became known as the Meeker Massacre. Josephine, her mother Arvilla Meeker, and Mrs. Shadruck Price and her two children were taken captive and held hostage by the Ute tribe for 23 days.

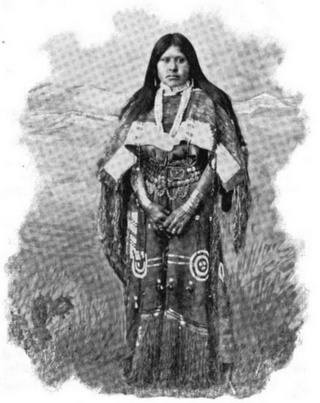

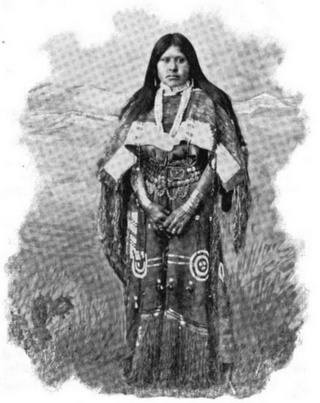

Chipeta or White Singing Bird was a Native American leader, and the second wife of Chief Ouray of the Uncompahgre Ute tribe. Born a Kiowa Apache, she was raised by the Utes in what is now Conejos, Colorado. An advisor and confidant of her husband, Chipeta continued as a leader of her people after his death in 1880.

Ouray is an unincorporated village of the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation, located in west‑central Uintah County, Utah, United States.

Samuel Austin Cherry was an lieutenant in the United States Army. He spent most of his military career at posts in Wyoming and Nebraska. In 1879, he participated in the Battle of Milk Creek, where he commanded a group of 20 men in a rear-guard action that allowed their column to make an orderly withdrawal from a superior Ute force and establish a defensive position. Cherry was able to bring all 20 of his men back to the column.

Fort Crawford, first known as Cantonment at Uncompahgre, was a U.S. military post along the Uncompahgre River, south of Montrose in Montrose County, Colorado. It was built following the Meeker Massacre and operated from 1880 to 1891. A historical marker is located somewhat near the site of the fort, which is on private property.

Colorow was a Ute chief of the Ute Mountain Utes, skilled horseman, and warrior. He was involved in treaty negotiations with the U.S. government. In 1879, he fought during the Meeker Massacre. Eight years later, his family members were attacked during Colorow's War. He was placed in the Jefferson County Hall of Fame in recognition of for the contributions that "he made to our county and, indeed, our state and nation."

Shawsheen (Shoshine) otherwise known as She-towitch, or Susan, was a Native American woman who was a part of the Tabeguache (Uncompahgre) Ute tribe and sister to Chief Ouray. She is known for her capture by the Cheyenne and Arapaho in 1860 or 1861, her protection and care for Arvilla and Josephine Meeker during their captivity, as well as her role within the politics of her tribe as a female leader alongside her sister-in-law, Chipeta.

The Seuvarits Utes are a band of the Northern Ute tribe of Native Americans that traditionally inhabited the area surrounding present-day Moab, Utah, near the Grand River and the Green River. The Seuvarits were among the Ute bands that were involved in the Black Hawk War. The Seuvarits and other Ute bands were eventually relocated onto reservations by the United States government after their population severely declined after exposure to disease and war during the latter half of the 19th century.

Thomas Tipton Thornburgh was a career soldier, starting during the American Civil War when he enlisted with the Sixth East Tennessee Volunteers for the Union Army. Mid-war, he left the ranks to study at the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating in 1867. After serving in the west for a number of years, he was made the commander of Fort Steele and Indian scout who received orders to establish peace with the White River Utes. With about 180 men, Thornburgh entered the White River Ute Reservation on September 16, 1879, and he and 13 of his men where killed during the Battle of Milk Creek.