| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

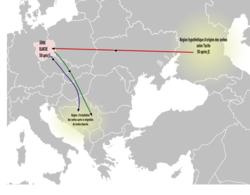

The Serbs trace their history to the 6th- and 7th-century Slavic migrations to the Balkans. Settling in various parts of the Balkans, Early Slavs assimilated local Byzantine populations (primarily descendants of different paleo-Balkan peoples) and other former Roman citizens. Their descendants later coalesced into different Balkan Slavic medieval states. [1] [2]