Satisficing is a decision-making strategy or cognitive heuristic that entails searching through the available alternatives until an acceptability threshold is met. The term satisficing, a portmanteau of satisfy and suffice, was introduced by Herbert A. Simon in 1956, although the concept was first posited in his 1947 book Administrative Behavior. Simon used satisficing to explain the behavior of decision makers under circumstances in which an optimal solution cannot be determined. He maintained that many natural problems are characterized by computational intractability or a lack of information, both of which preclude the use of mathematical optimization procedures. He observed in his Nobel Prize in Economics speech that "decision makers can satisfice either by finding optimum solutions for a simplified world, or by finding satisfactory solutions for a more realistic world. Neither approach, in general, dominates the other, and both have continued to co-exist in the world of management science".

In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of contradictory information and the mental toll of it. Relevant items of information include a person's actions, feelings, ideas, beliefs, values, and things in the environment. Cognitive dissonance is typically experienced as psychological stress when persons participate in an action that goes against one or more of those things. According to this theory, when two actions or ideas are not psychologically consistent with each other, people do all in their power to change them until they become consistent. The discomfort is triggered by the person's belief clashing with new information perceived, wherein the individual tries to find a way to resolve the contradiction to reduce their discomfort.

Online dating, also known as Internet dating, Virtual dating, or Mobile app dating, is a relatively recent method used by people with a goal of searching for and interacting with potential romantic or sexual partners, via the internet. An online dating service is a company that promotes and provides specific mechanisms for the practice of online dating, generally in the form of dedicated websites or software applications accessible on personal computers or mobile devices connected to the internet. A wide variety of unmoderated matchmaking services, most of which are profile-based with various communication functionalities, is offered by such companies.

In psychology, decision-making is regarded as the cognitive process resulting in the selection of a belief or a course of action among several possible alternative options. It could be either rational or irrational. The decision-making process is a reasoning process based on assumptions of values, preferences and beliefs of the decision-maker. Every decision-making process produces a final choice, which may or may not prompt action.

Managerial economics is a branch of economics involving the application of economic methods in the organizational decision-making process. Economics is the study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Managerial economics involves the use of economic theories and principles to make decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources.

A choice is the range of different things from which a being can choose. The arrival at a choice may incorporate motivators and models. For example, a traveler might choose a route for a journey based on the preference of arriving at a given destination at a specified time. The preferred route can then account for information such as the length of each of the possible routes, the amount of fuel in the vehicle, traffic conditions, etc.

Consumer behavior is the study of individuals, groups, or organizations and all the activities associated with the purchase, use and disposal of goods and services. Consumer behaviour consists of how the consumer's emotions, attitudes, and preferences affect buying behaviour. Consumer behaviour emerged in the 1940–1950s as a distinct sub-discipline of marketing, but has become an interdisciplinary social science that blends elements from psychology, sociology, social anthropology, anthropology, ethnography, ethnology, marketing, and economics.

Status quo bias is an emotional bias; a preference for the maintenance of one's current or previous state of affairs, or a preference to not undertake any action to change this current or previous state. The current baseline is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss or gain. Corresponding to different alternatives, this current baseline or default option is perceived and evaluated by individuals as a positive.

Casual sex is sexual activity that takes place outside a romantic relationship and implies an absence of commitment, emotional attachment, or familiarity between sexual partners. Examples are sexual activity while casually dating, one-night stands, prostitution or swinging.

Buyer's remorse is the sense of regret after having made a purchase. It is frequently associated with the purchase of an expensive item such as a vehicle or real estate.

Choice-supportive bias or post-purchase rationalization is the tendency to retroactively ascribe positive attributes to an option one has selected and/or to demote the forgone options. It is part of cognitive science, and is a distinct cognitive bias that occurs once a decision is made. For example, if a person chooses option A instead of option B, they are likely to ignore or downplay the faults of option A while amplifying or ascribing new negative faults to option B. Conversely, they are also likely to notice and amplify the advantages of option A and not notice or de-emphasize those of option B.

The Paradox of Choice – Why More Is Less is a book written by American psychologist Barry Schwartz and first published in 2004 by Harper Perennial. In the book, Schwartz argues that eliminating consumer choices can greatly reduce anxiety for shoppers. The book analyses the behavior of different types of people. This book argues that the dramatic explosion in choice—from the mundane to the profound challenges of balancing career, family, and individual needs—has paradoxically become a problem instead of a solution and how our obsession with choice encourages us to seek that which makes us feel worse.

Choice architecture is the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to decision makers, and the impact of that presentation on decision-making. For example, each of the following:

Sustainable consumer behavior is the sub-discipline of consumer behavior that studies why and how consumers do or do not incorporate sustainability priorities into their consumption behavior. It studies the products that consumers select, how those products are used, and how they are disposed of in pursuit of consumers' sustainability goals.

Consumer confusion is a state of mind that leads to consumers making imperfect purchasing decisions or lacking confidence in the correctness of their purchasing decisions.

A context effect is an aspect of cognitive psychology that describes the influence of environmental factors on one's perception of a stimulus. The impact of context effects is considered to be part of top-down design. The concept is supported by the theoretical approach to perception known as constructive perception. Context effects can impact our daily lives in many ways such as word recognition, learning abilities, memory, and object recognition. It can have an extensive effect on marketing and consumer decisions. For example, research has shown that the comfort level of the floor that shoppers are standing on while reviewing products can affect their assessments of product's quality, leading to higher assessments if the floor is comfortable and lower ratings if it is uncomfortable. Because of effects such as this, context effects are currently studied predominantly in marketing.

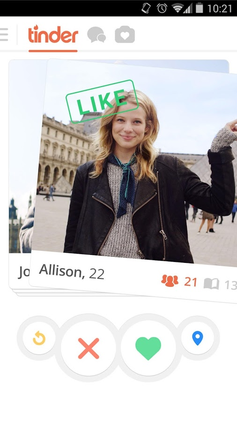

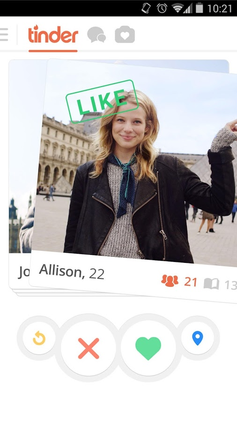

Tinder is an online dating and geosocial networking application. In Tinder, users "swipe right" to like or "swipe left" to dislike other users' profiles, which include their photos, a short bio, and a list of their interests. Tinder uses a "double opt-in" system where both users must like each other before they can exchange messages.

The default effect, a concept within the study of nudge theory, explains the tendency for an agent to generally accept the default option in a strategic interaction. The default option is the course of action that the agent, or chooser, will obtain if he or she does not specify a particular course of action. The default effect has broad applications for firms attempting to 'nudge' their customers in the direction of the firm's optimal outcome. Experiments and observational studies show that making an option a default increases the likelihood that such an option is chosen. There are two broad classes of defaults: mass defaults and personalised defaults. Setting or changing defaults has been proposed and applied by firms as an effective way of influencing behaviour—for example, with respect to setting air-conditioner temperature settings, giving consent to receive e-mail marketing, or automatic subscription renewals.

Maximization is a style of decision-making characterized by seeking the best option through an exhaustive search through alternatives. It is contrasted with satisficing, in which individuals evaluate options until they find one that is "good enough".

An online dating application is an online dating service presented through a mobile phone application (app), often taking advantage of a smartphone's GPS location capabilities, always on-hand presence, easy access to digital photo galleries and mobile wallets to enhance the traditional nature of online dating. These apps aim to simplify and speed up the process of sifting through potential dating partners, chatting, flirting, and potentially meeting or becoming romantically involved over traditional online dating services.