Podocnemididae is a family of pleurodire (side-necked) turtles, once widely distributed. Most of its 41 genera and 57 species are now extinct. Seven of its eight surviving species are native to South America: the genus Peltocephalus, with two species, only one of which is extant ; and the genus Podocnemis, with six living species of South American side-necked river turtles and four extinct. There is also one genus native to Madagascar: Erymnochelys, the Madagascan big-headed turtle, whose single species E. madagascariensis.

Archelon is an extinct marine turtle from the Late Cretaceous, and is the largest turtle ever to have been documented, with the biggest specimen measuring 4.6 m (15 ft) from head to tail and 2.2–3.2 t in body mass. It is known only from the Pierre Shale and has one species, A. ischyros. In the past, the genus also contained A. marshii and A. copei, though these have been reassigned to Protostega and Kansastega, respectively. The genus was named in 1895 by American paleontologist George Reber Wieland based on a skeleton from South Dakota, who placed it into the extinct family Protostegidae. The leatherback sea turtle was once thought to be its closest living relative, but now, Protostegidae is thought to be a completely separate lineage from any living sea turtle.

The Cochin forest cane turtle, also known as Kavalai forest turtle, forest cane turtle or simply cane turtle, is a rare turtle from the Western Ghats of India. Described in 1912, its type locality is given as "Near Kavalai in the Cochin State Forests, inhabiting dense forest, at an elevation of about 1500 feet above sea level". Only two specimens were found at that time, and no scientist saw this turtle for the next 70 years. It was rediscovered in 1982, and since then a number of specimens have been found and some studies have been conducted about its phylogeny and ecology.

Macroplata is an extinct genus of Early Jurassic rhomaleosaurid plesiosaur which grew up to 4.65 metres (15.3 ft) in length. Like other plesiosaurs, Macroplata probably lived on a diet of fish, using its sharp needle-like teeth to catch prey. Its shoulder bones were fairly large, indicating a powerful forward stroke for fast swimming. Macroplata also had a relatively long neck, twice the length of the skull, in contrast to pliosaurs. It is known from a nearly complete skeleton NHMUK PV R5488 from the Blue Lias Formation (Hettangian) of Harbury, Warwickshire, UK.

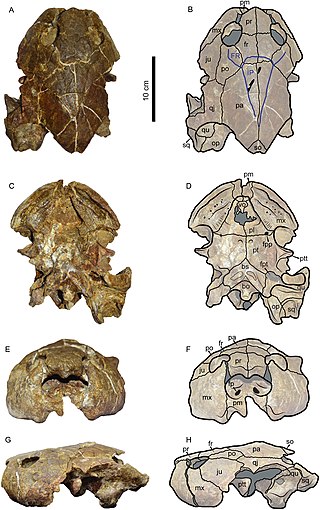

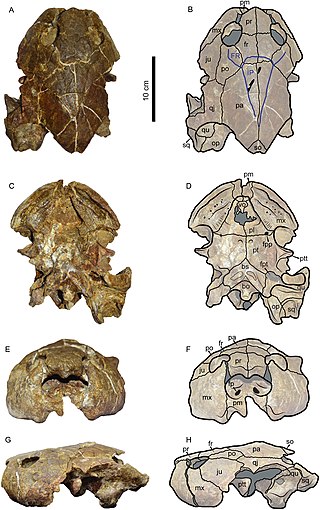

Stupendemys is an extinct genus of freshwater side-necked turtle, belonging to the family Podocnemididae. It is the largest freshwater turtle known to have existed, with a carapace over 2 meters long. Its fossils have been found in northern South America, in rocks dating from the Middle Miocene to the very start of the Pliocene, about 13 to 5 million years ago. Male specimens are known to have possessed bony horns growing from the front edges of the shell and the discovery of the fossil of a young adult shows that the carapace of these turtles flattens with age. A fossil skull described in 2021 indicates that Stupendemys was a generalist feeder.

Pliosaurus is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic of Europe and South America. Most European species of Pliosaurus measured around 8 metres (26 ft) long and weighed about 5 metric tons, but P. rossicus and P. funkei would have been one of the largest plesiosaurs of all time, exceeding 10 metres (33 ft) in length. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent reviews found only six to be valid, while the validity of two additional species awaits a petition to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature. Currently, P. brachyspondylus and P. macromerus are considered dubious, while P. portentificus is considered undiagnostic. Species of this genus are differentiated from other pliosaurids based on seven autapomorphies, including teeth that are triangular in cross section. Their diet would have included fish, cephalopods, and marine reptiles.

Kambara is an extinct genus of mekosuchine crocodylian that lived during the Eocene epoch in Australia. It is generally thought to have been a semi-aquatic generalist, living a lifestyle similar to many of today's crocodiles. Four species are currently recognised, the sympatric Kambara murgonensis and Kambara implexidens from sediments near Murgon, the poorly preserved Kambara molnari from the Rundle Formation and the youngest of the four, Kambara taraina, also from the Rundle Formation. Kambara were medium-sized crocodilians, with mature specimens generally reaching lengths from 3–4 m (9.8–13.1 ft).

The Big-headed Amazon River turtle, also known as the big-headed sideneck, is a species of turtle in the family Podocnemididae.

Laganosuchus is an extinct genus of stomatosuchid crocodyliform. Fossils have been found from Niger and Morocco and date back to the Upper Cretaceous.

Carbonemys cofrinii is an extinct giant podocnemidid turtle known from the Middle Paleocene Cerrejón Formation of the Cesar-Ranchería Basin in northeastern Colombia. The formation is dated at around 60 to 57 million years ago, starting at about five million years after the KT extinction event.

Globidentosuchus is an extinct genus of basal caimanine crocodylian known from the late Middle to Late Miocene of the Middle and the Upper Members of the Urumaco Formation at Urumaco, Venezuela. Its skull was very short and robust, with large units of spherical teeth used to break the shells of molluscs as part of its durophagus diet. It is thought to be one of the most basal Caimanines, even sharing some traits with alligatorids.

Megalochelys is an extinct genus of tortoises that lived from the Miocene to Pleistocene. They are noted for their giant size, the largest known for any tortoise, with a maximum carapace length of over 2 m (6.5 ft) in M. atlas. The genus ranged from western India and Pakistan to as far east as Sulawesi and Timor in Indonesia, though the island specimens likely represent distinct species.

Basilemys is a large, terrestrial nanhsiungchelyid turtle from the Upper Cretaceous of North and Central America. Basilemys has been found in rocks dating to the Campanian and Maastrichtian subdivisions of the Late Cretaceous and is considered to be the largest terrestrial turtle of its time. In an analysis made by Sukhanov et al. on a nansiunghelyid turtle from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia, it was demonstrated that Asian nanhsiungchelyids gave rise to the North American nanhsiungchelyids.

Arisierpeton is an extinct genus of synapsids from the Early Permian Garber Formation of Richards Spur, Oklahoma. It contains a single species, Arisierpeton simplex.

Caiman brevirostris is an extinct species of caiman that lived during the Late Miocene, around 11.6 million years ago, to the end of the Miocene 5.3 million years ago in Acre and Amazonas, Brazil as well as Urumaco, Venezuela. Several specimens have been referred to the species, but only 3 of them are confidently placed in the species. C. brevirostris was originally named in 1987 on the basis of a single, incomplete rostrum with an associated mandibular ramus that had been found in Acre, Brazil. C. brevirostris is very distinct among Caiman species and caimaninae overall in that it preserves a characteristically short and robust skull that bears blunt posterior teeth that were built to break down harder foods. This was an adaption for durophagy, likely to crush shells of mollusks and clams which were common in the wetlands that C. brevirostris resided in.

Caninemys is an extinct genus of large freshwater side-necked turtle, belonging to the family Podocnemididae. Its fossils have been found in Brazil and Colombia, in rocks dating back from the middle to late Miocene.

Kyhytysuka is an extinct genus of ophthalmosaurian ichthyosaur from Early Cretaceous Colombia. The animal was previously assigned to the genus Platypterygius, but given its own genus in 2021. Kyhytysuka was a mid-sized ophthalmosaurian with heterodont dentition and several adaptations suggesting that it was a macropredatory vertebrate hunter living in shallow waters. It contains a single species, Kyhytysuka sachicarum.

Drazinderetes is a large bodied genus of soft shell turtle from the Middle Eocene Drazinda Formation of Pakistan. Its presence in the shallow marine deposits of the Drazinda Formation suggests that Drazinderetes may have been a partially or fully marine animal. Indetermined trionychine remains from the same formation may suggest that Drazinderetes could have been among the largest known turtles, with one entoplastron indicating a potential length of 1.5 to 2.1 meters. Drazinderetes currently consists of only a single species: Drazinderetes tethyensis.

Pachagnathus is an extinct genus of non-pterodactyloid pterosaur from the late Norian–early Rhaetian-aged Quebrada del Barro Formation of Argentina. It lived in the Late Triassic period, and is one of the only known definitive Triassic pterosaurs from the southern hemisphere. It is also one of the few known continental Triassic pterosaurs, indicating that the absence of early pterosaurs in both the southern hemisphere and terrestrial environments is likely a sampling bias, and not a true absence.

Gaffneylania is an extinct genus of meiolaniid turtle from the Eocene of Patagonia. Gaffneylania is among the earliest known meiolaniids and, much like its later relatives, possessed characteristic horns atop its head. The shell appears to have had a serrated margin. Gaffneylania is a monotypic genus, only containing a single species, Gaffneylania auricularis.