| Penicillium chrysogenum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Aspergillaceae |

| Genus: | Penicillium |

| Species: | P. chrysogenum |

| Binomial name | |

| Penicillium chrysogenum Thom (1910) | |

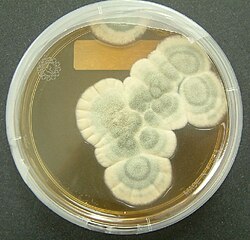

Penicillium chrysogenum (formerly known as Penicillium notatum) is a species of fungus in the genus Penicillium . It is common in temperate and subtropical regions and can be found on salted food products, [1] but it is mostly found in indoor environments, especially in damp or water-damaged buildings. [2] It has been recognised as a species complex that includes P. notatum, P. meleagrinum, and P. cyaneofulvum. [3] Molecular phylogeny has established that Alexander Fleming's first discovered penicillin-producing strain is of a distinct species, P. rubens , and not of P. notatum. [4] [5] It has rarely been reported as a cause of human disease. [6] It is the source of several β-lactam antibiotics, most significantly penicillin. Other secondary metabolites of P. chrysogenum include roquefortine C, meleagrin, [7] chrysogine, [8] 6-MSA [9] YWA1/melanin, [10] andrastatin A, [11] fungisporin, [12] secalonic acids, sorbicillin, [13] [14] and PR-toxin. [15]

Contents

Like the many other species of the genus Penicillium , P. chrysogenum usually reproduces by forming dry chains of spores (or conidia) from brush-shaped conidiophores. The conidia are typically carried by air currents to new colonisation sites. In P. chrysogenum, the conidia are blue to blue-green, and the mold sometimes exudes a yellow pigment. However, P. chrysogenum cannot be identified based on colour alone. Observations of morphology and microscopic features are needed to confirm its identity and DNA sequencing is essential to distinguish it from closely related species such as P. rubens. The sexual stage of P. chrysogenum was discovered in 2013 by mating cultures in the dark on oatmeal agar supplemented with biotin, after the mating types (MAT1-1 or MAT1-2) of the strains had been determined using PCR amplification. [16]

The airborne asexual spores of P. chrysogenum are important human allergens. Vacuolar and alkaline serine proteases have been implicated as the major allergenic proteins. [17]

P. chrysogenum has been used industrially to produce penicillin and xanthocillin X, to treat pulp mill waste, and to produce the enzymes polyamine oxidase, phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, and glucose oxidase. [15] [18]