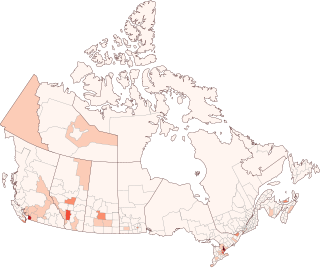

There has been a significant history of Chinese immigration to Canada, with the first settlement of Chinese people in Canada being in the 1780s. The major periods of Chinese immigration would take place from 1858 to 1923 and 1947 to the present day, reflecting changes in the Canadian government's immigration policy.

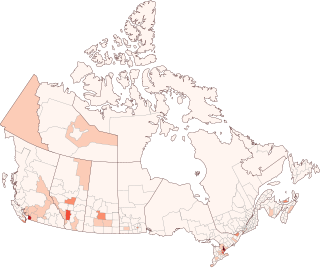

Chinese Canadians are Canadians of full or partial Han Chinese ancestry, which includes both naturalized Chinese immigrants and Canadian-born Chinese. They comprise a subgroup of East Asian Canadians which is a further subgroup of Asian Canadians. Demographic research tends to include immigrants from Mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau, as well as overseas Chinese who have immigrated from Southeast Asia and South America into the broadly defined Chinese Canadian category.

Frederick Buscombe, was the 11th Mayor of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He served from 1905 to 1906. A glassware and china merchant, he was a President of the Vancouver Board of Trade in 1900.

Events from the year 1898 in Canada.

Events from the year 1882 in Canada.

Chinatown is a neighbourhood in Vancouver, British Columbia, and is Canada's largest Chinatown. Centred around Pender Street, it is surrounded by Gastown to the north, the Downtown financial and central business districts to the west, the Georgia Viaduct and the False Creek inlet to the south, the Downtown Eastside and the remnant of old Japantown to the northeast, and the residential neighbourhood of Strathcona to the southeast.

John Hamilton Gray, was a politician in the Province of New Brunswick, Canada, a jurist, and one of the Fathers of Confederation. He should not be confused with John Hamilton Gray, a Prince Edward Island politician in the same era.

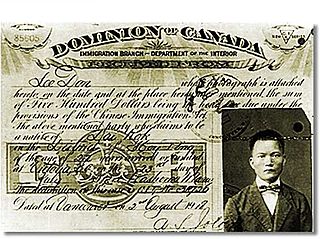

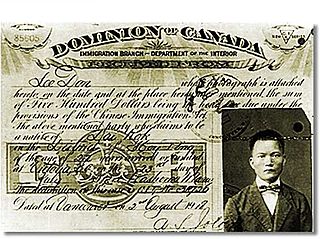

The Chinese head tax was a fixed fee charged to each Chinese person entering Canada. The head tax was first levied after the Canadian parliament passed the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 and it was meant to discourage Chinese people from entering Canada after the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). The tax was abolished by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which outright prevented all Chinese immigration except for that of business people, clergy, educators, students, and some others.

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1885 was an act of the Parliament of Canada that placed a head tax of $50 on all Chinese immigrants entering Canada. It was based on the recommendations of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration, which were published in 1885.

Canadian immigration and refugee law concerns the area of law related to the admission of foreign nationals into Canada, their rights and responsibilities once admitted, and the conditions of their removal. The primary law on these matters is in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, whose goals include economic growth, family reunification, and compliance with humanitarian treaties.

The Chinatown in Victoria, British Columbia is the oldest Chinatown in Canada and the second oldest in North America after San Francisco. Victoria's Chinatown had its beginnings in the mid-nineteenth century in the mass influx of miners from California to what is now British Columbia in 1858. It remains an actively inhabited place and continues to be popular with residents and visitors, many of whom are Chinese-Canadians. Victoria's Chinatown is now surrounded by cultural, entertainment venues as well as being a venue itself. Chinatown is now conveniently just minutes away from other sites of interests such as the Save-On-Foods Memorial Centre, Bay Centre, Empress Hotel, Market Square, and others.

The history of immigration to Canada details the movement of people to modern-day Canada. The modern Canadian legal regime was founded in 1867, but Canada also has legal and cultural continuity with French and British colonies in North America that go back to the 17th century, and during the colonial era, immigration was a major political and economic issue with Britain and France competing to fill their colonies with loyal settlers. Until then, the land that now makes up Canada was inhabited by many distinct Indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples contributed significantly to the culture and economy of the early European colonies to which was added several waves of European immigration. More recently, the source of migrants to Canada has shifted away from Europe and towards Asia and Africa. Canada's cultural identity has evolved constantly in tandem with changes in immigration patterns.

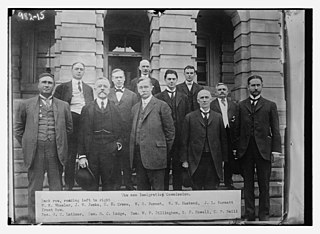

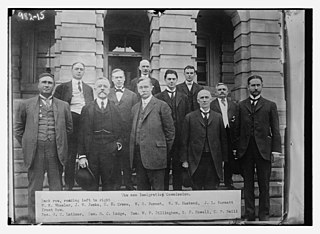

The United States Immigration Commission (also known as the Dillingham Commission after its chairman, Republican Senator William P. Dillingham, was a bipartisan special committee formed in February 1907 by the United States Congress and President Theodore Roosevelt, to study the origins and consequences of recent immigration to the United States. This was in response to increasing political concerns about the effects of immigration and its brief was to report on the social, economic, and moral state of the nation. During its time in action the Commission employed a staff of more than 300 people for over 3 years, spent better than a million dollars and accumulated mass data.

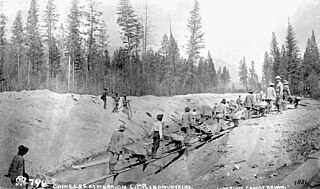

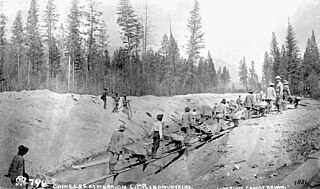

The Vancouver anti-Chinese riots of 1886, sometimes called the Winter Riots because of the time of year they took place, were prompted by the engagement of cheap Chinese labour by the Canadian Pacific Railway to clear Vancouver's West End of large Douglas fir trees and stumps, passing over the thousands of unemployed men from the rest of Canada who had arrived looking for work.

The Royal Commission on Opium was a British Royal Commission that investigated the opium trade in British India in 1893–1895, particularly focusing on the medical impacts of opium consumption within India. Set up by Prime Minister William Gladstone’s government in response to political pressure from the anti-opium movement to ban non-medical sales of opium in India, it ultimately defended the existing system in which opium sales to the public were legal but regulated.

Racism in Canada traces both historical and contemporary racist community attitudes, as well as governmental negligence and political non-compliance with United Nations human rights standards and incidents in Canada. Contemporary Canada is the product of indigenous First Nations combined with multiple waves of immigration, predominantly from Europe and in modern times, from Asia.

The Vancouver riots occurred September 7–9, 1907, in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. At about the same time there were similar anti-Asian riots in Bellingham, Washington, San Francisco, and other West Coast cities. They were not coordinated but instead reflected common underlying anti-immigration attitudes. Agitation for direct action was led by labour unions and small business. Damage to Asian-owned property was extensive.

The history of Chinese Canadians in British Columbia began with the first recorded visit by Chinese people to North America in 1788. Some 30–40 men were employed as shipwrights at Nootka Sound in what is now British Columbia, to build the first European-type vessel in the Pacific Northwest, named the North West America. Large-scale immigration of Chinese began seventy years later with the advent of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush of 1858. During the gold rush, settlements of Chinese grew in Victoria and New Westminster and the "capital of the Cariboo" Barkerville and numerous other towns, as well as throughout the colony's interior, where many communities were dominantly Chinese. In the 1880s, Chinese labour was contracted to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. Following this, many Chinese began to move eastward, establishing Chinatowns in several of the larger Canadian cities.

Paper sons or paper daughters is a term used to refer to Chinese people who were born in China and illegally immigrated to the United States and Canada by purchasing documentation which stated that they were blood relatives to Chinese people who had already received U.S. or Canadian citizenship or residency. Typically it would be relation by being a son or a daughter. Several historical events such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and San Francisco earthquake of 1906 caused the illegal documents to be produced.

People of Chinese descent have lived in Colorado since the mid-nineteenth century, when many immigrated from China for work. Chinese immigrants have made an undeniable impact on Colorado's history and culture. While the Chinese moved throughout the state, including building small communities on the Western Slope and establishing Chinatown, Denver, the presence of Chinese Coloradans diminished significantly due to violence and discriminatory policies. As of 2018, there were 45,273 Chinese Americans living in Colorado.