A robot is a machine—especially one programmable by a computer—capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically. A robot can be guided by an external control device, or the control may be embedded within. Robots may be constructed to evoke human form, but most robots are task-performing machines, designed with an emphasis on stark functionality, rather than expressive aesthetics.

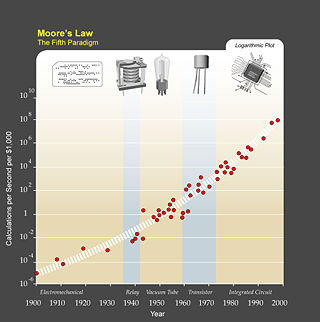

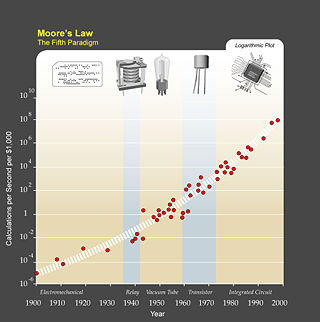

The technological singularity—or simply the singularity—is a hypothetical future point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unforeseeable consequences for Human civilization. According to the most popular version of the singularity hypothesis, I. J. Good's intelligence explosion model of 1965, an upgradable intelligent agent could eventually enter a positive feedback loop of self-improvement cycles, each successive; and more intelligent generation appearing more and more rapidly, causing a rapid increase ("explosion") in intelligence which would ultimately result in a powerful superintelligence, qualitatively far surpassing all human intelligence.

Federico Faggin is an Italian-American physicist, engineer, inventor and entrepreneur. He is best known for designing the first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004. He led the 4004 (MCS-4) project and the design group during the first five years of Intel's microprocessor effort. Faggin also created, while working at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1968, the self-aligned MOS (metal-oxide-semiconductor) silicon-gate technology (SGT), which made possible MOS semiconductor memory chips, CCD image sensors, and the microprocessor. After the 4004, he led development of the Intel 8008 and 8080, using his SGT methodology for random logic chip design, which was essential to the creation of early Intel microprocessors. He was co-founder and CEO of Zilog, the first company solely dedicated to microprocessors, and led the development of the Zilog Z80 and Z8 processors. He was later the co-founder and CEO of Cygnet Technologies, and then Synaptics.

Futurists are people whose specialty or interest is futurology or the attempt to systematically explore predictions and possibilities about the future and how they can emerge from the present, whether that of human society in particular or of life on Earth in general.

Human-centered computing (HCC) studies the design, development, and deployment of mixed-initiative human-computer systems. It is emerged from the convergence of multiple disciplines that are concerned both with understanding human beings and with the design of computational artifacts. Human-centered computing is closely related to human-computer interaction and information science. Human-centered computing is usually concerned with systems and practices of technology use while human-computer interaction is more focused on ergonomics and the usability of computing artifacts and information science is focused on practices surrounding the collection, manipulation, and use of information.

Futures studies, futures research, futurism research, futurism, or futurology is the systematic, interdisciplinary and holistic study of social/technological advancement, and other environmental trends; often for the purpose of exploring how people will live and work in the future. Predictive techniques, such as forecasting, can be applied, but contemporary futures studies scholars emphasize the importance of systematically exploring alternatives. In general, it can be considered as a branch of the social sciences and an extension to the field of history. Futures studies seeks to understand what is likely to continue and what could plausibly change. Part of the discipline thus seeks a systematic and pattern-based understanding of past and present, and to explore the possibility of future events and trends.

Service design is the activity of planning and arranging people, infrastructure, communication and material components of a service in order to improve its quality, and the interaction between the service provider and its users. Service design may function as a way to inform changes to an existing service or create a new service entirely.

In futurology, especially in Europe, the term foresight has become widely used to describe activities such as:

Futures techniques used in the multi-disciplinary field of futurology by futurists in Americas and Australasia, and futurology by futurologists in EU, include a diverse range of forecasting methods, including anticipatory thinking, backcasting, simulation, and visioning. Some of the anticipatory methods include, the delphi method, causal layered analysis, environmental scanning, morphological analysis, and scenario planning.

Emerging technologies are technologies whose development, practical applications, or both are still largely unrealized. These technologies are generally new but also include old technologies finding new applications. Emerging technologies are often perceived as capable of changing the status quo.

Design thinking refers to the set of cognitive, strategic and practical procedures used by designers in the process of designing, and to the body of knowledge that has been developed about how people reason when engaging with design problems.

Intelligent Environments (IE) are spaces with embedded systems and information and communication technologies creating interactive spaces that bring computation into the physical world and enhance occupants experiences. "Intelligent environments are spaces in which computation is seamlessly used to enhance ordinary activity. One of the driving forces behind the emerging interest in highly interactive environments is to make computers not only genuine user-friendly but also essentially invisible to the user".

Kent Larson is an architect and Professor of the Practice at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Larson is currently director of the City Science research group at the MIT Media Lab, and co-director with Lord Norman Foster of the Norman Foster Institute on Sustainable Cities based in Madrid. His research is focused on urban design, modeling and simulation, compact transformable housing, and ultralight autonomous mobility on demand. He has established an international consortium of City Science Network labs, and is a founder of multiple MIT Media Lab spin-off companies, including Ori Living and L3cities.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to robotics:

Living labs are open innovation ecosystems in real-life environments using iterative feedback processes throughout a lifecycle approach of an innovation to create sustainable impact. They focus on co-creation, rapid prototyping & testing and scaling-up innovations & businesses, providing joint-value to the involved stakeholders. In this context, living labs operate as intermediaries/orchestrators among citizens, research organisations, companies and government agencies/levels.

Genevieve Bell is the Vice-Chancellor of the Australian National University and an Australian cultural anthropologist. She is best known for her work at the intersection of cultural practice research and technological development, and for being an industry pioneer of the user experience field. Bell was the inaugural director of the Autonomy, Agency and Assurance Innovation Institute (3Ai), which was co-founded by the Australian National University (ANU) and CSIRO’s Data61, and a Distinguished Professor of the ANU College of Engineering, Computing and Cybernetics. From 2021 to December 2023, she was the inaugural Director of the new ANU School of Cybernetics. She also holds the university's Florence Violet McKenzie Chair, and is the first SRI International Engelbart Distinguished Fellow. Bell is also a Senior Fellow and Vice President at Intel. She is widely published, and holds 13 patents.

Design fiction is a design practice aiming at exploring and criticising possible futures by creating speculative, and often provocative, scenarios narrated through designed artifacts. It is a way to facilitate and foster debates, as explained by futurist Scott Smith: "... design fiction as a communication and social object creates interactions and dialogues around futures that were missing before. It helps make it real enough for people that you can have a meaningful conversation with".

The Creative Science Foundation (CSf) is a non-profit organization, established on 4 November 2011 in London, England, that advocates a synergetic relationship between creative arts and sciences as a means to fostering innovation. It is best known for its use of science fiction prototyping as an ideation, communication and prototyping tool for product innovation. The foundation's main modus-operandi are the organisation or sponsorship of vacation-schools, workshops, seminars, conferences, journals, publications and projects.

Micro-SFP (μSFP) describes an ultra-short science-fiction story written for the specific purpose of capturing inventive ideas for product or service innovations. It is a combination of three concepts, first science-fiction prototyping, second flash fiction and finally, Twitter and texting.

Threatcasting is a conceptual framework used to help multidisciplinary groups envision future scenarios. It is also a process that enables systematic planning against threats ten years in the future. Utilizing the threatcasting process, groups explore possible future threats and how to transform the future they desire into reality while avoiding undesired futures. Threatcasting is a continuous, multiple-step process with inputs from social science, technical research, cultural history, economics, trends, expert interviews, and science fiction storytelling. These inputs inform the exploration of potential visions of the future.