Jakob Nielsen is a Danish web usability consultant, human–computer interaction researcher, and co-founder of Nielsen Norman Group. He was named the “guru of Web page usability” in 1998 by The New York Times and the “king of usability” by Internet Magazine.

In human–computer interaction, WIMP stands for "windows, icons, menus, pointer", denoting a style of interaction using these elements of the user interface. Other expansions are sometimes used, such as substituting "mouse" and "mice" for menus, or "pull-down menu" and "pointing" for pointer.

MultiLisp is a functional programming language, a dialect of the language Lisp, and of its dialect Scheme, extended with constructs for parallel computing execution and shared memory. These extensions involve side effects, rendering MultiLisp nondeterministic. Along with its parallel-programming extensions, MultiLisp also had some unusual garbage collection and task scheduling algorithms. Like Scheme, MultiLisp was optimized for symbolic computing. Unlike some parallel programming languages, MultiLisp incorporated constructs for causing side effects and for explicitly introducing parallelism.

End-user development (EUD) or end-user programming (EUP) refers to activities and tools that allow end-users – people who are not professional software developers – to program computers. People who are not professional developers can use EUD tools to create or modify software artifacts and complex data objects without significant knowledge of a programming language. In 2005 it was estimated that by 2012 there would be more than 55 million end-user developers in the United States, compared with fewer than 3 million professional programmers. Various EUD approaches exist, and it is an active research topic within the field of computer science and human-computer interaction. Examples include natural language programming, spreadsheets, scripting languages, visual programming, trigger-action programming and programming by example.

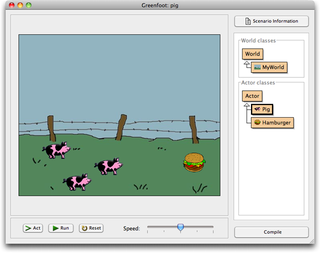

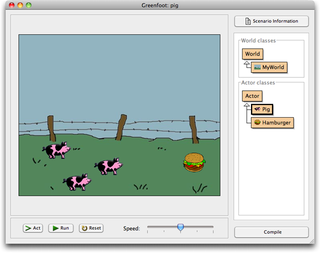

Greenfoot is an integrated development environment using Java or Stride designed primarily for educational purposes at the high school and undergraduate level. It allows easy development of two-dimensional graphical applications, such as simulations and interactive games.

Thread Level Speculation (TLS), also known as Speculative Multi-threading, or Speculative Parallelization, is a technique to speculatively execute a section of computer code that is anticipated to be executed later in parallel with the normal execution on a separate independent thread. Such a speculative thread may need to make assumptions about the values of input variables. If these prove to be invalid, then the portions of the speculative thread that rely on these input variables will need to be discarded and squashed. If the assumptions are correct the program can complete in a shorter time provided the thread was able to be scheduled efficiently.

Michael Ezra Saks is an American mathematician. He is currently the Department Chair of the Mathematics Department at Rutgers University (2017–) and from 2006 until 2010 was director of the Mathematics Graduate Program at Rutgers University. Saks received his Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1980 after completing his dissertation titled Duality Properties of Finite Set Systems under his advisor Daniel J. Kleitman.

Value sensitive design (VSD) is a theoretically grounded approach to the design of technology that accounts for human values in a principled and comprehensive manner. VSD originated within the field of information systems design and human-computer interaction to address design issues within the fields by emphasizing the ethical values of direct and indirect stakeholders. It was developed by Batya Friedman and Peter Kahn at the University of Washington starting in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Later, in 2019, Batya Friedman and David Hendry wrote a book on this topic called "Value Sensitive Design: Shaping Technology with Moral Imagination". Value Sensitive Design takes human values into account in a well-defined matter throughout the whole process. Designs are developed using an investigation consisting of three phases: conceptual, empirical and technological. These investigations are intended to be iterative, allowing the designer to modify the design continuously.

Eric Joel Horvitz is an American computer scientist, and Technical Fellow at Microsoft, where he serves as the company's first Chief Scientific Officer. He was previously the director of Microsoft Research Labs, including research centers in Redmond, WA, Cambridge, MA, New York, NY, Montreal, Canada, Cambridge, UK, and Bangalore, India.

Victoria Bellotti is a Senior CI researcher in the Member Experience Team at Netflix. Previously, she was a user experience manager for growth at Lyft and a research fellow at the Palo Alto Research Center. She is known for her work in the area of personal information management and task management, but from 2010 to 2018 she began researching context-aware peer-to-peer transaction partner matching and motivations for using peer-to-peer marketplaces which led to her joining Lyft. Victoria also serves as an adjunct professor in the Jack Baskin School of Engineering at University of California Santa Cruz, on the editorial board of the Personal and Ubiquitous Computing and as an associate editor for the International Journal of HCI. She is a researcher in the Human–computer interaction community. In 2013 she was awarded membership of the ACM SIGCHI Academy for her contributions to the field and professional community of human computer interaction.

Mindfulness and technology is a movement in research and design, that encourages the user to become aware of the present moment, rather than losing oneself in a technological device. This field encompasses multidisciplinary participation between design, psychology, computer science, and religion. Mindfulness stems from Buddhist meditation practices and refers to the awareness that arises through paying attention on purpose in the present moment, and in a non-judgmental mindset. In the field of Human-Computer Interaction, research is being done on Techno-spirituality — the study of how technology can facilitate feelings of awe, wonder, transcendence, and mindfulness and on Slow design, which facilitates self-reflection. The excessive use of personal devices, such as smartphones and laptops, can lead to the deterioration of mental and physical health. This area focuses on redesigning and creating technology to improve the wellbeing of its users.

Projector-camera systems (pro-cam), also called camera-projector systems, augment a local surface with a projected captured image of a remote surface, creating a shared workspace for remote collaboration and communication. Projector-camera systems may also be used for artistic and entertainment purposes. A pro-cam system consists of a vertical screen for implementing interpersonal space where front-facing videos are displayed, and a horizontal projected screen on the tabletop for implementing shared workspace where downward facing videos are overlapped. An automatically pre-warped image is sent to the projector to ensure that the horizontal screen appears undistorted.

Animal–computer interaction (ACI) is a field of research for the design and use of technology with, for and by animals covering different kinds of animals from wildlife, zoo and domesticated animals in different roles. It emerged from, and was heavily influenced by, the discipline of Human–computer interaction (HCI). As the field expanded, it has become increasingly multi-disciplinary, incorporating techniques and research from disciplines such as artificial intelligence (AI), requirements engineering (RE), and veterinary science.

Feminist HCI is a subfield of human-computer interaction (HCI) that applies feminist theory, critical theory and philosophy to social topics in HCI, including scientific objectivity, ethical values, data collection, data interpretation, reflexivity, and unintended consequences of HCI software. The term was originally used in 2010 by Shaowen Bardzell, and although the concept and original publication are widely cited, as of 2020 Bardzell's proposed frameworks have been rarely used since.

Jacob O. Wobbrock is a Professor in the University of Washington Information School and, by courtesy, in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington. He is Director of the ACE Lab, Associate Director and founding Co-Director Emeritus of the CREATE research center, and a founding member of the DUB Group and the MHCI+D degree program.

David Allen Kirby is an American professor of science communication studies at Cal Poly University in San Luis Obispo. He researches, writes about, and teaches science communication and the history of science. He is best known for his work showing how fictional narratives can be used in the process of design and for his studies on the use of scientists as consultants for Hollywood film productions.

Susanne Bødker is a Danish computer scientist known for her contributions to human–computer interaction, computer-supported cooperative work, and participatory design, including the introduction of activity theory to human–computer interaction. She is a professor of computer science at Aarhus University, and a member of the CHI Academy.

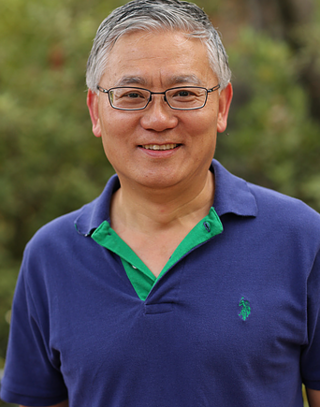

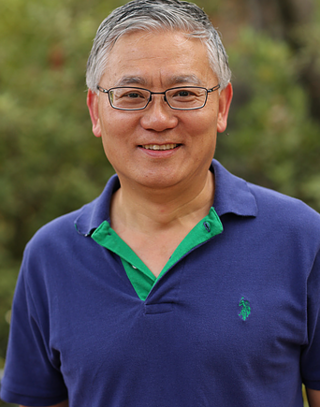

Shumin Zhai is a Chinese-born American Canadian Human–computer interaction (HCI) research scientist and inventor. He is known for his research specifically on input devices and interaction methods, swipe-gesture-based touchscreen keyboards, eye-tracking interfaces, and models of human performance in human-computer interaction. His studies have contributed to both foundational models and understandings of HCI and practical user interface designs and flagship products. He previously worked at IBM where he invented the ShapeWriter text entry method for smartphones, which is a predecessor to the modern Swype keyboard. Dr. Zhai's publications have won the ACM UIST Lasting Impact Award and the IEEE Computer Society Best Paper Award, among others, and he is most known for his research specifically on input devices and interaction methods, swipe-gesture-based touchscreen keyboards, eye-tracking interfaces, and models of human performance in human-computer interaction. Dr. Zhai is currently a principal scientist at Google where he leads and directs research, design, and development of human-device input methods and haptics systems.

Batya Friedman is an American professor in the University of Washington Information School. She is also an adjunct professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering and adjunct professor in the Department of Human-Centered Design and Engineering, where she directs the Value Sensitive Design Research Lab. She received her PhD in learning sciences from the University of California, Berkeley School of Education in 1988, and has an undergraduate degree from Berkeley in computer science and mathematics.

Speculative design is a design practice concerned with future design proposals of a critical nature. The term was popularised by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby as a subsidiary of critical design. The aim is not to present commercially-driven design proposals but to design proposals that identify and debate crucial issues that might happen in the future. Speculative design is concerned with future consequences and implications of the relationship between science, technology, and humans. It problematizes this relation by proposing provocative future design scenarios where technology and design implications are accentuated. These design proposals are meant to trigger debates about the future rather than marketing products.