The French Resistance was a collection of groups that fought the Nazi occupation of France and the collaborationist Vichy régime in France during the Second World War. Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women who conducted guerrilla warfare and published underground newspapers. They also provided first-hand intelligence information, and escape networks that helped Allied soldiers and airmen trapped behind Axis lines. The Resistance's men and women came from many parts of French society, including émigrés, academics, students, aristocrats, conservative Roman Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, liberals, anarchists, communists, and some fascists. The proportion of French people who participated in organized resistance has been estimated at from one to three percent of the total population.

Pierre Jean Marie Laval was a French politician. During the Third Republic, he served as Prime Minister of France from 1931 to 1932 and from 1935 to 1936. He again occupied the post during the German occupation, from 1942 to 1944.

The National Front for an Independent France, better known simply as National Front was a World War II French Resistance movement created to unite all of the Resistance Organizations together to fight the Nazi occupation forces and Vichy France under Marshall Pétain.

Marcel Déat was a French politician. Initially a socialist and a member of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), he led a breakaway group of right-wing Neosocialists out of the SFIO in 1933. During the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, he founded the collaborationist National Popular Rally (RNP). In 1944, he became Minister of Labour and National Solidarity in Pierre Laval's government in Vichy, before escaping to the Sigmaringen enclave along with Vichy officials after the Allied landings in Normandy. Condemned in absentia for collaborationism, he died while still in hiding in Italy.

The Francs-tireurs et partisans – main-d'œuvre immigrée (FTP-MOI) were a sub-group of the Francs-tireurs et partisans (FTP) organization, a component of the French Resistance. A wing composed mostly of foreigners, the MOI maintained an armed force to oppose the German occupation of France during World War II. The Main-d'œuvre immigrée was the "Immigrant Movement" of the FTP.

The Military Administration in France was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called zone occupée was established in June 1940, and renamed zone nord in November 1942, when the previously unoccupied zone in the south known as zone libre was also occupied and renamed zone sud.

The Riom Trial was an attempt by the Vichy France regime, headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain, to prove that the leaders of the French Third Republic (1870–1940) had been responsible for France's defeat by Germany in 1940. The trial was held in the city of Riom in central France, and had mainly political aims – namely to project the responsibility of defeat onto the leaders of the left-wing Popular Front government that had been elected 3 May 1936.

The épuration légale was the wave of official trials that followed the Liberation of France and the fall of the Vichy regime. The trials were largely conducted from 1944 to 1949, with subsequent legal action continuing for decades afterward.

The Révolution nationale was the official ideological program promoted by the Vichy regime which had been established in July 1940 and led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Pétain's regime was characterized by anti-parliamentarism, personality cultism, xenophobia, state-sponsored anti-Semitism, promotion of traditional values, rejection of the constitutional separation of powers, modernity, and corporatism, as well as opposition to the theory of class conflict. Despite its name, the ideological policies were reactionary rather than revolutionary as the program opposed almost every change introduced to French society by the French Revolution.

The National Popular Rally was a French political party and one of the main collaborationist parties under the Vichy regime of World War II.

Vichy France, officially the French State, was the French rump state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. It was named after its seat of government, the city of Vichy. Officially independent, but with half of its territory occupied under the harsh terms of the 1940 armistice with Nazi Germany, it adopted a policy of collaboration. Though Paris was nominally its capital, the government established itself in the resort town of Vichy in the unoccupied "free zone", where it remained responsible for the civil administration of France as well as its colonies. The occupation of France by Nazi Germany at first affected only the northern and western portions of the country, but in November 1942 the Germans and Italians occupied the remainder of Metropolitan France, ending any pretence of independence by the Vichy government.

René Belin was a French trade unionist and politician. In the 1930s he became one of the leaders of the French General Confederation of Labour.

Jean Bichelonne was a French businessman and member of the Vichy government that governed France during World War II following the occupation of France by Nazi Germany.

Although no precise estimates exist, the number of French soldiers captured by Nazi Germany during the Battle of France between May and June 1940 is generally recognised around 1.8 million, equivalent to around 10 percent of the total adult male population of France at the time. After a brief period of captivity in France, most of the prisoners were deported to Germany. In Germany, prisoners were incarcerated in Stalag or Oflag prison camps, according to rank, but the vast majority were soon transferred to work details (Kommandos) working in German agriculture or industry. Prisoners from the French colonial empire, however, remained in camps in France with poor living conditions as a result of Nazi racial ideologies.

The Sigmaringen enclave was the exiled remnant of France's Nazi-sympathizing Vichy government which fled to Germany during the Liberation of France near the end of World War II in order to avoid capture by the advancing Allied forces. Installed in the requisitioned Sigmaringen Castle as seat of the government-in-exile, Vichy French leader Philippe Pétain and a number of other collaborators awaited the end of the war.

Led by Philippe Pétain, the Vichy regime that replaced the French Third Republic in 1940 chose the path of collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. This policy included the Bousquet-Oberg accords of July 1942 that formalized the collaboration of the French police with the German police. This collaboration was manifested in particular by anti-Semitic measures taken by the Vichy government, and by its active participation in the genocide.

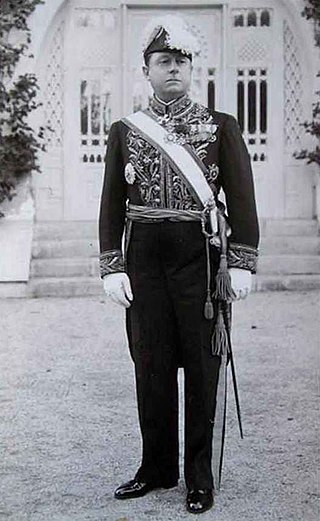

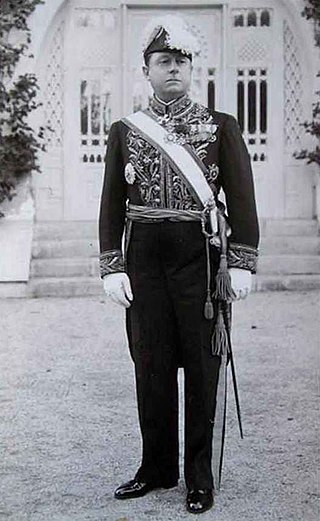

Marcel Peyrouton was a French diplomat and politician. He served as the French Minister of the Interior from 1940 to 1941, during Vichy France. He served as the French Ambassador to Argentina from 1936 to 1940, and from 1941 to 1942. He served as the Governor-General of French Algeria in 1943. He was acquitted in 1948.

The Recusant's Insignia is a French medal to honour French citizens who evaded the Compulsory Work Service (S.T.O.) in Nazi Germany and therefore participated in the fight against the invader.

The Railway Workers' Federation is the largest trade union representing workers on the railways in France.

The Government of Vichy France was the collaborationist ruling regime or government in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War. Of contested legitimacy, it was headquartered in the town of Vichy in occupied France, but it initially took shape in Paris under Marshal Philippe Pétain as the successor to the French Third Republic in June 1940. The government remained in Vichy for four years, and fled into exile to Germany in September 1944 after the Allied invasion of France. It operated as a government-in-exile until April 1945, when the Sigmaringen enclave was taken by Free French forces. Pétain was brought back to France, by then under control of the Provisional French Republic, and put on trial for treason.