Dhimmī or muʿāhid (معاهد) is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligation under sharia to protect the individual's life, property, as well as freedom of religion, in exchange for loyalty to the state and payment of the jizya tax, in contrast to the zakat, or obligatory alms, paid by the Muslim subjects. Dhimmi were exempt from military service and other duties assigned specifically to Muslims if they paid the poll tax (jizya) but were otherwise equal under the laws of property, contract, and obligation.

The Almohad Caliphate or Almohad Empire was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al-Andalus) and North Africa.

People of the Book, or Ahl al-Kitāb, is a classification in Islam for the adherents of those religions that are regarded by Muslims as having received a divine revelation from Allah, generally in the form of a holy scripture. The classification chiefly refers to pre-Islamic Abrahamic religions. In the Quran, they are identified as the Jews, the Christians, the Sabians, and—according to some interpretations—the Zoroastrians. Beginning in the 8th century, this recognition was extended to other groups, such as the Samaritans, and, controversially, Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs, among others. In most applications, "People of the Book" is simply used by Muslims to refer to the followers of Judaism and Christianity, with which Islam shares many values, guidelines, and principles.

Jizya, or jizyah, is a type of taxation historically levied on non-Muslim subjects of a state governed by Islamic law. The Quran and hadiths mention jizya without specifying its rate or amount, and the application of jizya varied in the course of Islamic history. However, scholars largely agree that early Muslim rulers adapted some of the existing systems of taxation and modified them according to Islamic religious law.

The golden age of Jewish culture in Spain was a Muslim ruled era of Spain, with the state name of Al-Andalus, lasting 800 years, whose state lasted from 711 to 1492 A.D. This coincides with the Islamic Golden Age within Muslim ruled territories, while Christian Europe experienced the Middle Ages.

The yellow badge, also known as the yellow patch, the Jewish badge, or the yellow star, was an accessory that Jews were required to wear in certain non-Jewish societies throughout history. A Jew's ethno-religious identity, which would be denoted by the badge, would help to mark them as an outsider. Legislation that mandated Jewish subjects to wear such items has been documented in some Middle Eastern caliphates and in some European kingdoms during the medieval period and the early modern period. The most recent usage of yellow badges was during World War II, when Jews living in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe were ordered to wear a yellow Star of David to keep their Jewish identity disclosed to the public in the years leading up to the Holocaust.

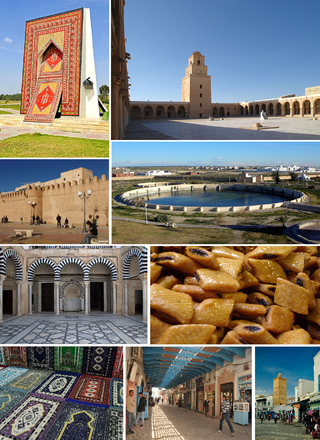

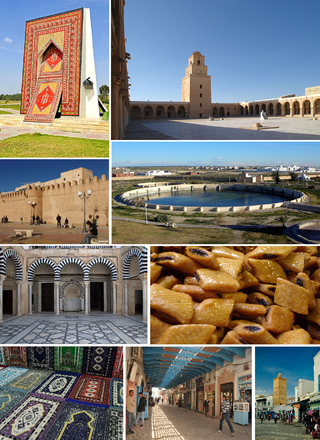

Kairouan, also spelled El Qayrawān or Kairwan, is the capital of the Kairouan Governorate in Tunisia and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city was founded by the Umayyads around 670, in the period of Caliph Mu'awiya ; this is when it became an important centre for Sunni Islamic scholarship and Quranic learning, attracting Muslims from various parts of the world. The Mosque of Uqba is situated in the city.

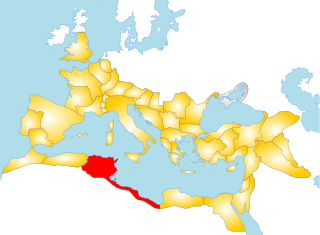

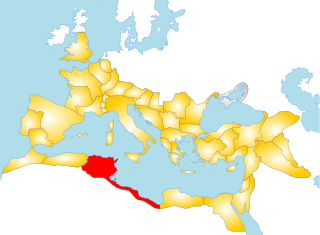

Ifriqiya, also known as al-Maghrib al-Adna or Oriental Berberia, was a medieval historical region comprising today's Tunisia, eastern Algeria, and Tripolitania. It included all of what had previously been the Byzantine province of Africa Proconsularis and extended beyond it, but did not include the Mauretanias.

The Hafsids were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descent who ruled Ifriqiya from 1229 to 1574.

Abu Zakariya Yahya (Arabic: أبو زكريا يحيى بن حفص, Abu Zakariya Yahya I ben Abd al-Wahid was the founder and first sultan of the Hafsid dynasty in Ifriqiya. He was the grandson of Sheikh Abu al-Hafs, the leader of the Hintata and second in command of the Almohads after Abd al-Mu'min.

The history of the Jews in Tunisia extends nearly two thousand years to the Punic era. The Jewish community in Tunisia grew following successive waves of immigration and proselytism before its development was hampered in late antiquity by anti-Jewish measures in the Byzantine Empire. After the Muslim conquest of Tunisia, Tunisian Judaism went through periods of relative freedom or even cultural apogee to times of more marked discrimination, with Jews being treated as second-class citizens (dhimmi). The community formerly used its own dialect of Arabic. The arrival of Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula, often through Livorno, greatly altered the country. Its economic, social and cultural situation has improved markedly with the advent of the French protectorate before being compromised during the Second World War, with the occupation of the country by the Axis.

Moroccan Jews constitute an ancient community. Before the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, there were about 265,000 Jews in the country, which gave Morocco the largest Jewish community in the Muslim world, but by 2017 only 2,000 or so remained. Jews in Morocco, originally speakers of Berber languages, Judeo-Moroccan Arabic or Judaeo-Spanish, were the first in the country to adopt the French language in the mid-19th century, and unlike among the Muslim population French remains the main language of members of the Jewish community there.

The Jewish hat, also known as the Jewish cap, Judenhut (German) or Latin pileus cornutus, was a cone-shaped pointed hat, often white or yellow, worn by Jews in Medieval Europe. Initially worn by choice, its wearing was enforced in some places in Europe after the 1215 Fourth Council of the Lateran for adult male Jews to wear while outside a ghetto to distinguish them from others. Like the Phrygian cap that it often resembles, the hat may have originated in pre-Islamic Persia, as a similar hat was worn by Babylonian Jews.

Zunnar was a distinctive belt or girdle, part of the clothing that Dhimmi were required to wear within the Islamic caliphate regions to distinguish them from Muslims. Though not always enforced, the zunnar served, together with a set of other rules, as a covert tool of discrimination.

Berber Jews are the Jewish communities of the Maghreb, in North Africa, who historically spoke Berber languages. Between 1950 and 1970 most emigrated to France, the United States, or Israel.

The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians Under Islam is a history book on the dhimmi peoples - the non-Arab and non-Muslim communities subjected to Muslim domination after the conquest of their territories by Arabs by Bat Ye'or. The book was first published in French in 1980, and was titled Le Dhimmi : Profil de l'opprimé en Orient et en Afrique du Nord depuis la conquête Arabe. It was translated into English and published in 1985 under the name The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians Under Islam. The book provides a wealth of documents from diverse periods and regions, many of them previously unpublished and makes a clear distinction between factual history and biased interpretations, providing a comprehensive study of dhimmi populations that draws on numerous original source materials to convey an accurate portrait of their status under Islamic rule.

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Karim al-Maghili, commonly known as Muhammad al-Maghili was a Berber 'alim from Tlemcen, the capital of the Kingdom of Tlemcen, now in modern-day Algeria. Al-Maghili was responsible for converting the ruling classes to Islam among Hausa, Fulani, and Tuareg peoples in West Africa.

Almohad doctrine or Almohadism was the ideology underpinning the Almohad movement, founded by Ibn Tumart, which created the Almohad Empire during the 12th to 13th centuries. Fundamental to Almohadism was Ibn Tumart's radical interpretation of tawḥid—"unity" or "oneness"—from which the Almohads get their name: al-muwaḥḥidūn (المُوَحِّدون).

Maghrebi Arabs or North African Arabs are the inhabitants of the Maghreb region of North Africa whose ethnic identity is Arab, whose native language is Arabic and trace their ancestry to the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula. This ethnic identity is a product of the centuries-long Arab migration to the Maghreb since the 7th century, which changed the demographic scope of the Maghreb and was a major factor in the ethnic, linguistic and cultural Arabization of the Maghreb region. The descendants of the original Arab settlers who continue to speak Arabic as a first language currently form the single largest population group in North Africa.

Abū Shujā' Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥusayn al-Rūdhrāwarī, also known by the honorific "Zaḥīr al-Dīn", was an 11th-century government official and author who served as vizier for the Abbasid Caliphate twice, once briefly in 1078 and the second time from 1083/4 until 1094. He wrote a continuation to Miskawayh's history Tajārib al-umam. He also wrote a diwan of poetry, of which about 80 verses survive.