Roy Chapman Andrews was an American explorer, adventurer and naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politically disturbed China of the early 20th century into the Gobi Desert and Mongolia. The expeditions made important discoveries and brought the first-known fossil dinosaur eggs to the museum. Chapman's popular writing about his adventures made him famous.

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 20 interconnected buildings housing 45 permanent exhibition halls, in addition to a planetarium and a library. The museum collections contain about 35 million specimens of plants, animals, fungi, fossils, minerals, rocks, meteorites, human remains, and human cultural artifacts, as well as specialized collections for frozen tissue and genomic and astrophysical data, of which only a small fraction can be displayed at any given time. The museum occupies more than 2,500,000 sq ft (232,258 m2). AMNH has a full-time scientific staff of 225, sponsors over 120 special field expeditions each year, and averages about five million visits annually.

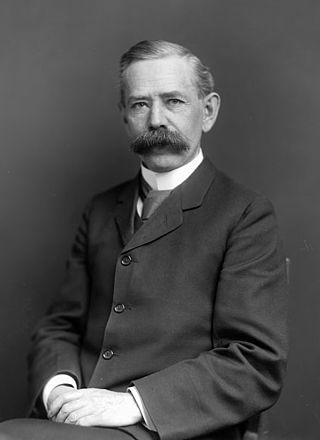

Daniel Giraud Elliot was an American zoologist and the founder of the American Ornithologist Union.

Carl Ethan Akeley was a pioneering American taxidermist, sculptor, biologist, conservationist, inventor, and nature photographer, noted for his contributions to American museums, most notably to the Milwaukee Public Museum, Field Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History. He is considered the father of modern taxidermy. He was the founder of the AMNH Exhibitions Lab, the interdisciplinary department that fuses scientific research with immersive design.

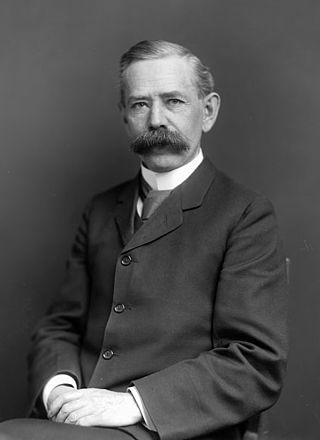

Frederick Courteney Selous, DSO was a British explorer, officer, professional hunter, and conservationist, famous for his exploits in Southeast Africa. His real-life adventures inspired Sir Henry Rider Haggard to create the fictional Allan Quatermain character. Selous was a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, Cecil Rhodes and Frederick Russell Burnham. He was pre-eminent within a group of big game hunters that included Abel Chapman and Arthur Henry Neumann. He was the older brother of the ornithologist and writer Edmund Selous.

James Rowland Ward (1848–1912) was a British taxidermist and founder of the firm Rowland Ward Limited of Piccadilly, London. The company specialised in and was renowned for its taxidermy work on birds and big-game trophies, but it did other types of work as well. In creating many practical items from antlers, feathers, feet, skins, and tusks, the Rowland Ward company made fashionable items from animal parts, such as zebra-hoof inkwells, antler furniture, and elephant-feet umbrella stands.

George Kruck Cherrie was an American naturalist and explorer. He collected numerous specimens on nearly forty expeditions that he joined for museums and several species have been named after him.

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for trophies, taxidermy, meat, and commercially valuable animal by-products. The term is often associated with the hunting of Africa's "Big Five" games, and Indian rhinoceros and Bengal tigers on the Indian subcontinent.

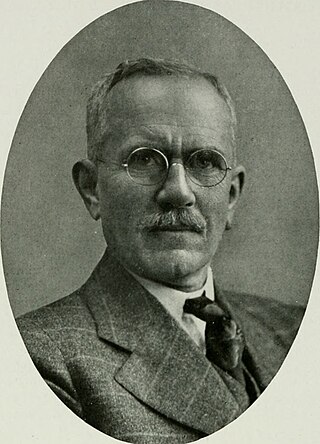

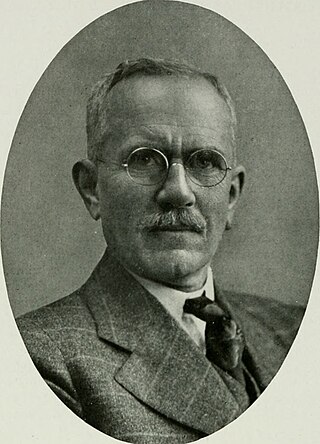

Edgar Alexander Mearns was an American surgeon, ornithologist and field naturalist. He was a founder of the American Ornithologists' Union.

Edmund Heller was an American zoologist. He was President of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums for two terms, from 1935-1936 and 1937-1938.

Loring's rat is a species of rodent in the family Muridae. It is found in Kenya and Tanzania. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry forests, dry savanna, and subtropical or tropical dry shrubland.

The King African mole-rat, King mole-rat, or Alpine mole-rat, is a burrowing rodent in the genus Tachyoryctes of family Spalacidae. It only occurs high on Mount Kenya, where it is common. Originally described as a separate species related to Aberdare Mountains African mole-rat, in 1910, some classify it as the same species as the East African mole-rat,.

James Lippitt Clark was a distinguished American explorer, sculptor and scientist.

Arthur Stannard Vernay was a noted English-born American art and antiques dealer, decorator, big-game hunter, and naturalist explorer. He sponsored and took part in expeditions across the world to collect biological specimens and cultural artifacts on behalf of the American Museum of Natural History. The Vernay-Faunthorpe Hall of South Asian mammals in the AMNH is named after him.

John Alden Loring was a mammalogist and field naturalist who served with the Bureau of Biological Survey, United States Department of Agriculture, the Bronx Zoological Park, the Smithsonian Institution and numerous expeditions collecting specimens in North America, Europe and Africa. A voluminous and careful traveling collector, Loring was recognized early in his career for 900 specimens collected, prepared and sent to the United States National Museum over a three-month period during an 1898 expedition through Scandinavia and northwestern Europe.

The James Simpson-Roosevelt Asiatic Expedition was a 1925 expedition sponsored by the Field Museum of Natural History and organized by Kermit Roosevelt and his brother Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

The William V. Kelley-Roosevelt Asiatic Expedition was a zoological expedition to Southeast Asia in 1928–1929 sponsored by the Field Museum of Natural History and organized by Kermit Roosevelt and his brother Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Peter C. "Pete" Pearson was an Australian-born game ranger, poacher, and professional hunter in East Africa.

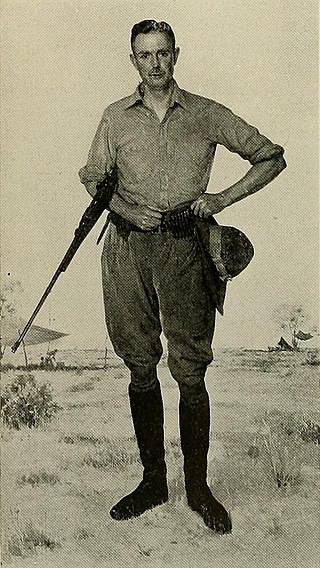

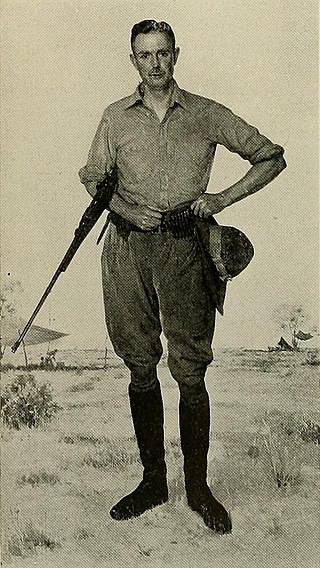

Leslie Jefferis Tarlton was an Australian big game hunter and entrepreneur in British East Africa. He was the leader of numerous safaris, including the Smithsonian-Roosevelt African Expedition of 1909–1910.