A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically, which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies, pronunciations, translation, etc. It is a lexicographical reference that shows inter-relationships among the data.

Machine translation is use of computational techniques to translate text or speech from one language to another, including the contextual, idiomatic and pragmatic nuances of both languages.

Jargon, or technical language, is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular communicative context and may not be well understood outside that context. The context is usually a particular occupation, but any ingroup can have jargon. The key characteristic that distinguishes jargon from the rest of a language is its specialized vocabulary, which includes terms and definitions of words that are unique to the context, and terms used in a narrower and more exact sense than when used in colloquial language. This can lead outgroups to misunderstand communication attempts. Jargon is sometimes understood as a form of technical slang and then distinguished from the official terminology used in a particular field of activity.

A translation memory (TM) is a database that stores "segments", which can be sentences, paragraphs or sentence-like units that have previously been translated, in order to aid human translators. The translation memory stores the source text and its corresponding translation in language pairs called “translation units”. Individual words are handled by terminology bases and are not within the domain of TM.

In computing, internationalization and localization (American) or internationalisation and localisation (British), often abbreviated i18n and l10n respectively, are means of adapting to different languages, regional peculiarities and technical requirements of a target locale.

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, organization, and many other modifications performed with an intention of producing a correct, consistent, accurate and complete piece of work.

Terminology is a group of specialized words and respective meanings in a particular field, and also the study of such terms and their use; the latter meaning is also known as terminology science. A term is a word, compound word, or multi-word expression that in specific contexts is given specific meanings—these may deviate from the meanings the same words have in other contexts and in everyday language. Terminology is a discipline that studies, among other things, the development of such terms and their interrelationships within a specialized domain. Terminology differs from lexicography, as it involves the study of concepts, conceptual systems and their labels (terms), whereas lexicography studies words and their meanings.

A language-for-specific-purposes dictionary is a reference work which defines the specialised vocabulary used by experts within a particular field, for example, architecture. The discipline that deals with these dictionaries is specialised lexicography. Medical dictionaries are well-known examples of the type.

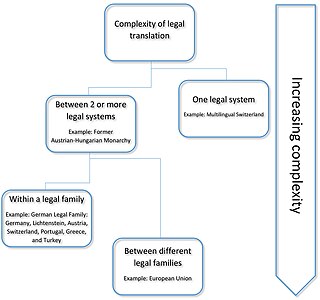

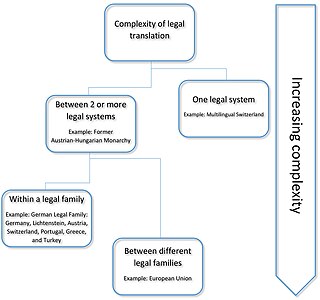

Legal translation is the translation of language used in legal settings and for legal purposes. Legal translation may also imply that it is a specific type of translation only used in law, which is not always the case. As law is a culture-dependent subject field, legal translation is not necessarily linguistically transparent. Intransparency in translation can be avoided somewhat by use of Latin legal terminology, where possible, but in non-western languages debates are centered on the origins and precedents of specific terms, such as in the use of particular Chinese characters in Japanese legal discussions.

Translation studies is an academic interdiscipline dealing with the systematic study of the theory, description and application of translation, interpreting, and localization. As an interdiscipline, translation studies borrows much from the various fields of study that support translation. These include comparative literature, computer science, history, linguistics, philology, philosophy, semiotics, and terminology.

In sociolinguistics, a register is a variety of language used for a particular purpose or particular communicative situation. For example, when speaking officially or in a public setting, an English speaker may be more likely to follow prescriptive norms for formal usage than in a casual setting, for example, by pronouncing words ending in -ing with a velar nasal instead of an alveolar nasal, choosing words that are considered more formal, such as father vs. dad or child vs. kid, and refraining from using words considered nonstandard, such as ain't and y'all.

Controlled vocabularies provide a way to organize knowledge for subsequent retrieval. They are used in subject indexing schemes, subject headings, thesauri, taxonomies and other knowledge organization systems. Controlled vocabulary schemes mandate the use of predefined, preferred terms that have been preselected by the designers of the schemes, in contrast to natural language vocabularies, which have no such restriction.

Professional writing is writing for reward or as a profession; as a product or object, professional writing is any form of written communication produced in a workplace environment or context that enables employees to, for example, communicate effectively among themselves, help leadership make informed decisions, advise clients, comply with federal, state, or local regulatory bodies, bid for contracts, etc. Professional writing is widely understood to be mediated by the social, rhetorical, and material contexts within which it is produced. For example, in a business office, a memorandum can be used to provide a solution to a problem, make a suggestion, or convey information. Other forms of professional writing commonly generated in the workplace include email, letters, reports, and instructions. In seeking to inform, persuade, instruct, stimulate debate, or encourage action from recipients, skilled professional writers make adjustments to different degrees of shared context, e.g., from a relatively accessible style useful for unsolicited contact letter to prospective clients to a technical report that relies on a highly specialized in-house vocabulary.

Cultural translation is the practice of translation while respecting and showing cultural differences. This kind of translation solves some issues linked to culture, such as dialects, food or architecture.

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction between translating and interpreting ; under this distinction, translation can begin only after the appearance of writing within a language community.

Technical translation is a type of specialized translation involving the translation of documents produced by technical writers, or more specifically, texts which relate to technological subject areas or texts which deal with the practical application of scientific and technological information. While the presence of specialized terminology is a feature of technical texts, specialized terminology alone is not sufficient for classifying a text as "technical" since numerous disciplines and subjects which are not "technical" possess what can be regarded as specialized terminology. Technical translation covers the translation of many kinds of specialized texts and requires a high level of subject knowledge and mastery of the relevant terminology and writing conventions.

Medical translation is the practice of translating various documents—training materials, medical bulletins, drug data sheets, etc.—for health care, medical devices, marketing, or for clinical, regulatory, and technical documentation. Most countries require that companies and organizations translate literature and labeling for medical devices or pharmaceuticals into their national language. Documents for clinical trials often require translation for local clinicians, patients, and regulatory representatives. Regulatory approval submissions typically must be translated. In addition to linguistic skills, medical translation requires specific training and subject matter knowledge because of the highly technical, sensitive, and regulated nature of medical texts.

Skopos theory is a theory in the field of translation studies that employs the prime principle of a purposeful action that determines a translation strategy. The intentionality of a translational action stated in a translation brief, the directives, and the rules guide a translator to attain the expected target text translatum.

Transcreation is a term coined from the words "translation" and "creation", and a concept used in the field of translation studies to describe the process of adapting a message from one language to another, while maintaining its intent, style, tone, and context. A successfully transcreated message evokes the same emotions and carries the same implications in the target language as it does in the source language. It is related to the concept of localization, which similarly involves comprehensively adapting a translated text for the target audience. Transcreation highlights the translator's creative role. Unlike many other forms of translation, transcreation also often involves adapting not only words, but video and images to the target audience. Transcreation theory was first developed in the field of literary translation, and began to be adapted for use global marketing and advertising in the early 21st century. The transcreation approach is also heavily used today in the translation of video games and mobile apps.

Sense-for-sense translation is the oldest norm for translating. It fundamentally means translating the meaning of each whole sentence before moving on to the next, and stands in normative opposition to word-for-word translation.