In the 19th century, the philosophies of the Enlightenment began to have a dramatic effect, the landmark works of philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Jean-Jacques Rousseau influencing new generations of thinkers. In the late 18th century a movement known as Romanticism began; it validated strong emotion as an authentic not of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as trepidation, horror and terror and awe. Key ideas that sparked changes in philosophy were the fast progress of science; evolution, as postulated by Vanini, Diderot, Lord Monboddo, Erasmus Darwin, Lamarck, Goethe, and Charles Darwin; and what might now be called emergent order, such as the free market of Adam Smith within nation states. Pressures for egalitarianism, and more rapid change culminated in a period of revolution and turbulence that would see philosophy change as well.

Legal positivism is a school of thought of analytical jurisprudence largely developed by legal thinkers in the 18th and 19th centuries, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Austin. While Bentham and Austin developed legal positivist theory, empiricism set the theoretical foundations for such developments to occur. The most prominent legal positivist writing in English has been H. L. A. Hart, who in 1958 found common usages of "positivism" as applied to law to include the contentions that:

- laws are commands of human beings

- there is no necessary connection between law and morality, that is, between law as it is and as it ought to be.

- analysis of legal concepts is worthwhile and is to be distinguished from history or sociology of law, as well as from criticism or appraisal of law, for example with regard to its moral value or to its social aims or functions

- a legal system is a closed, logical system in which correct decisions can be deduced from predetermined legal rules without reference to social considerations

- moral judgments, unlike statements of fact, cannot be established or defended by rational argument, evidence, or proof

Roberto Felice Ardigò was an Italian philosopher. He was an influential leader of Italian positivism and a former Roman Catholic priest.

In philosophy and models of scientific inquiry, postpositivism is a metatheoretical stance that critiques and amends positivism. While positivists emphasize independence between the researcher and the researched person, postpositivists accept that theories, background, knowledge and values of the researcher can influence what is observed. Postpositivists pursue objectivity by recognizing the possible effects of biases. While positivists emphasize quantitative methods, postpositivists consider both quantitative and qualitative methods to be valid approaches.

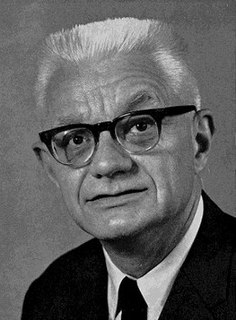

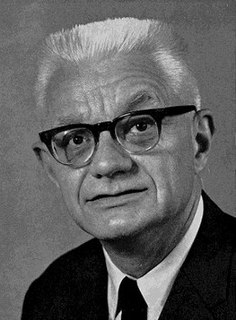

Carl Gustav "Peter" Hempel was a German writer and philosopher. He was a major figure in logical empiricism, a 20th-century movement in the philosophy of science. He is especially well known for his articulation of the deductive-nomological model of scientific explanation, which was considered the "standard model" of scientific explanation during the 1950s and 1960s. He is also known for the raven paradox.

Sociology as a scholarly discipline emerged primarily out of the Enlightenment thought, shortly after the French Revolution, as a positivist science of society. Its genesis owed to various key movements in the philosophy of science and the philosophy of knowledge. Social analysis in a broader sense, however, has origins in the common stock of philosophy and necessarily pre-dates the field. Modern academic sociology arose as a reaction to modernity, capitalism, urbanization, rationalization, secularization, colonization and imperialism. Late-19th-century sociology demonstrated a particularly strong interest in the emergence of the modern nation state; its constituent institutions, its units of socialization, and its means of surveillance. An emphasis on the concept of modernity, rather than the Enlightenment, often distinguishes sociological discourse from that of classical political philosophy.

The philosophy of social science is the study of the logic, methods, and foundations of social sciences such as psychology, economics, and political science. Philosophers of social science are concerned with the differences and similarities between the social and the natural sciences, causal relationships between social phenomena, the possible existence of social laws, and the ontological significance of structure and agency.

In social theory and philosophy, antihumanism is a theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about humanity and the human condition. Central to antihumanism is the view that concepts of "human nature", "man", or "humanity" should be rejected as historically relative or metaphysical.

Verificationism, also known as the verification idea or the verifiability criterion of meaning, is the philosophical doctrine that only statements that are empirically verifiable are cognitively meaningful, or else they are truths of logic (tautologies).

Altruism is an ethical doctrine that holds that the moral value of an individual's actions depend solely on the impact on other individuals, regardless of the consequences on the individual itself. James Fieser states the altruist dictum as: "An action is morally right if the consequences of that action are more favorable than unfavorable to everyone except the agent." Auguste Comte's version of altruism calls for living for the sake of others. One who holds to either of these ethics is known as an "altruist."

The history of the social sciences has origin in the common stock of Western philosophy and shares various precursors, but began most intentionally in the early 19th century with the positivist philosophy of science. Since the mid-20th century, the term "social science" has come to refer more generally, not just to sociology, but to all those disciplines which analyse society and culture; from anthropology to linguistics to media studies.

The law of three stages is an idea developed by Auguste Comte in his work The Course in Positive Philosophy. It states that society as a whole, and each particular science, develops through three mentally conceived stages: (1) the theological stage, (2) the metaphysical stage, and (3) the positive stage.

Gabino Barreda was a Mexican physician and philosopher oriented to French positivism.

Religion of Humanity is a secular religion created by Auguste Comte, the founder of positivist philosophy. Adherents of this religion have built chapels of Humanity in France and Brazil.

Knowledge and Human Interests is a 1968 book by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author gives an account of the development of the modern natural and human sciences. He criticizes Sigmund Freud, arguing that psychoanalysis is a branch of the humanities rather than a science, and provides a critique of Friedrich Nietzsche.