Christian theosophy, also known as Boehmian theosophy and theosophy, refers to a range of positions within Christianity that focus on the attainment of direct, unmediated knowledge of the nature of divinity and the origin and purpose of the universe. They have been characterized as mystical philosophies. Theosophy is considered part of Western esotericism, which believes that hidden knowledge or wisdom from the ancient past offers a path to illumination and salvation.

Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, often known as Madame Blavatsky, was a Russian and American mystic and author who co-founded the Theosophical Society in 1875. She gained an international following as the primary founder of Theosophy as a belief system.

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the Theosophy movement, and Henry Steel Olcott, the society's first president. It draws upon a wide array of influences among them older European philosophies and movements such as Neoplatonism and occultism, as well as parts of Asian religious traditions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam.

Ascended masters in a number of movements in the theosophical tradition are held to be spiritually enlightened beings who in past incarnations were ordinary humans, but who have undergone a series of spiritual transformations originally called initiations.

Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology, published in 1877, is a book of esoteric philosophy and Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's first major self-published major work text and a key doctrine in her self-founded Theosophical movement.

Djwal Khul, is believed by some Theosophists and others to be a Tibetan disciple in "The Ageless Wisdom" esoteric tradition. The texts describe him as a member of the 'Spiritual Hierarchy', or 'Brotherhood', of Mahatmas, one of the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom, defined as the spiritual guides of mankind and teachers of ancient cosmological, metaphysical, and esoteric principles that form the origin of all the world's great philosophies, mythologies and spiritual traditions. According to Theosophical writings, Djwal Khul is said to work on furthering the spiritual evolution of our planet through the teachings offered in the 24 books by Alice Bailey of Esoteric Teachings published by The Lucis Trust ; he is said to have telepathically transmitted the teachings to Bailey and is thus regarded by her followers as the communications director of the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom.

The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett is a book published in 1923 by A. Trevor Barker. (ISBN 1-55700-086-7) According to Theosophical teachings, the letters were written between 1880 and 1884 by Koot Hoomi and Morya to A. P. Sinnett. The letters were previously quoted in several theosophical books, but not published in full. The letters were important to the movement due to their discussions on the theosophical cosmos and spiritual hierarchy. From 1939, the original letters were in the possession of the British Museum but later the British Library.

Theosophical teachings have borrowed some concepts and terms from Buddhism. Some theosophists like Helena Blavatsky, Helena Roerich and Henry Steel Olcott also became Buddhists. Henry Steel Olcott helped shape the design of the Buddhist flag. Tibetan Buddhism was popularised in the West at first mainly by Theosophists including Evans-Wentz and Alexandra David-Neel.

In Theosophy, Maitreya or Lord Maitreya is an advanced spiritual entity and high-ranking member of a reputed hidden spiritual hierarchy, the Masters of the Ancient Wisdom. According to Theosophical doctrine, one of the hierarchy's functions is to oversee the evolution of humankind; in concert with this function Maitreya is said to hold the "Office of the World Teacher". Theosophical texts posit that the purpose of this Office is to facilitate the transfer of knowledge about the true constitution and workings of Existence to humankind. Humanity is thereby assisted on its presumed cyclical, but ever progressive, evolutionary path. Reputedly, one way the knowledge transfer is accomplished is by Maitreya occasionally manifesting or incarnating in the physical realm; the manifested entity then assumes the role of World Teacher of Humankind.

Within the system of Theosophy, developed by occultist Helena Blavatsky and others since the second half of the 19th century, Theosophical mysticism draws upon various existing disciplines and mystical models, including Neo-platonism, Gnosticism, Western esotericism, Freemasonry, Hinduism and Buddhism.

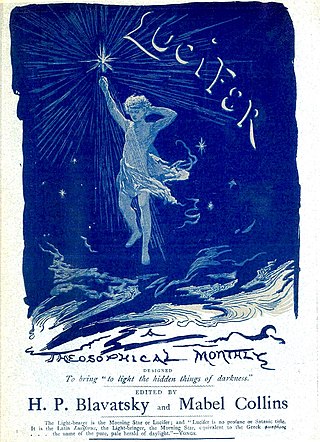

"Is Theosophy a Religion?" is an editorial published in November 1888 in the theosophical magazine Lucifer; it was compiled by Helena Blavatsky. It was included in the 10th volume of the author's Collected Writings. According to Arnold Kalnitsky, in the article it is about the problems of religion from the Theosophical point of view.

Theosophy is a religious and philosophical system established in the United States in the late 19th century. Founded primarily by Russian mystic and spiritualist Helena Blavatsky, and based largely on her writings, it draws heavily from both older European philosophies such as Gnosticism and Neoplatonism and Indian religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Although many adherents maintain that Theosophy is not a religion, it is variably categorized by religious scholars as both a new religious movement and a form of occultism from within Western esotericism.

Esoteric Buddhism is a book originally published in 1883 in London; it was compiled by a member of the Theosophical Society, A. P. Sinnett. It was one of the first books written for the purpose of explaining theosophy to the general public, and was "made up of the author's correspondence with an Indian mystic." This is the most significant theosophical work of the author. According to Goodrick-Clarke, it "disseminated the basic teachings of Theosophy in its new Asian cast."

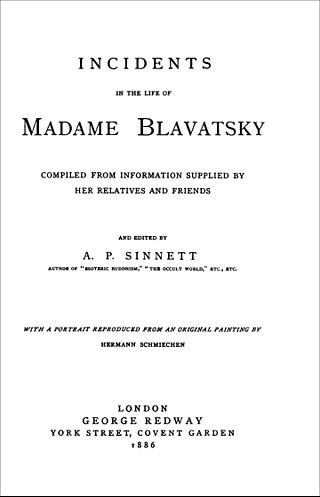

Incidents in the Life of Madame Blavatsky: compiled from information supplied by her relatives and friends is a book originally published in 1886 in London; it was compiled by a member of the Theosophical Society, A. P. Sinnett, who was the first biographer of H. P. Blavatsky. Sinnett describes the many unusual incidents in Blavatsky's life beginning from her childhood in Russia, and asserts that Blavatsky had "an early connection with the supernatural world;" Sinnett also writes about Blavatksy's short, unlucky marriage and "decade of extensive global travels," about her period of learning in Tibet, and the "criticism she received about some of her 'phenomena' and practices."

"The Esoteric Character of the Gospels" is an article published in three parts: in November-December 1887, and in February 1888, in the theosophical magazine Lucifer; it was written by Helena Blavatsky. It was included in the 8th volume of the author's Collected Writings. In 1888, for this work, the author was awarded Subba Row medal.

Christianity and Theosophy, for more than a hundred years, have had a "complex and sometimes troubled" relationship. The Christian faith was the native religion of the great majority of Western Theosophists, but many came to Theosophy through a process of opposition to Christianity. According to professor Robert S. Ellwood, "the whole matter has been a divisive issue within Theosophy."

"What Are The Theosophists?" is an editorial published in October 1879 in the theosophical magazine The Theosophist. It was compiled by Helena Blavatsky and it was included the second volume of the Blavatsky Collected Writings.

"What Is Theosophy?" is an editorial published in October 1879 in the Theosophical magazine The Theosophist. It was compiled by Helena Blavatsky and included into the 2nd volume of the Blavatsky Collected Writings. According to a doctoral thesis by Tim Rudbøg, in this "important" article Blavatsky "began conceptualizing her idea of 'Theosophy'."

Hinduism is regarded by modern Theosophy as one of the main sources of "esoteric wisdom" of the East. The Theosophical Society was created in a hope that Asian philosophical-religious ideas "could be integrated into a grand religious synthesis." Prof. Antoine Faivre wrote that "by its content and its inspiration" the Theosophical Society is greatly dependent on Eastern traditions, "especially Hindu; in this, it well reflects the cultural climate in which it was born." A Russian Indologist Alexander Senkevich noted that the concept of Helena Blavatsky's Theosophy was based on Hinduism. According to Encyclopedia of Hinduism, "Theosophy is basically a Western esoteric teaching, but it resonated with Hinduism at a variety of points."

According to some literary and religious studies scholars, modern Theosophy had a certain influence on contemporary literature, particularly in forms of genre fiction such as fantasy and science fiction. Researchers claim that Theosophy has significantly influenced the Irish literary renaissance of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, notably in such figures as W. B. Yeats and G. W. Russell.