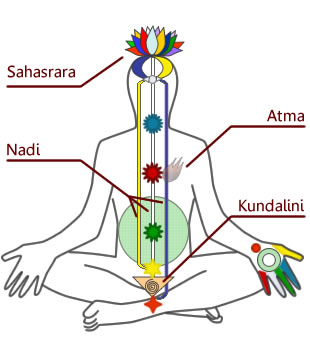

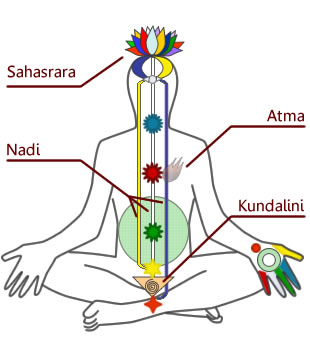

A chakra is one of the various focal points used in a variety of ancient meditation practices, collectively denominated as Tantra, part of the inner traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.

In Hinduism, kundalini is a form of divine feminine energy believed to be located at the base of the spine, in the muladhara. It is an important concept in Śhaiva Tantra, where it is believed to be a force or power associated with the divine feminine or the formless aspect of the Goddess. This energy in the body, when cultivated and awakened through tantric practice, is believed to lead to spiritual liberation. Kuṇḍalinī is associated with the goddess Parvati or Adi Parashakti, the supreme being in Shaktism, and with the goddesses Bhairavi and Kubjika. The term, along with practices associated with it, was adopted into Hatha Yoga in the 9th century. It has since then been adopted into other forms of Hinduism as well as modern spirituality and New Age thought.

Tantra is an esoteric yogic tradition that developed on the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE onwards in both Hinduism and Buddhism.

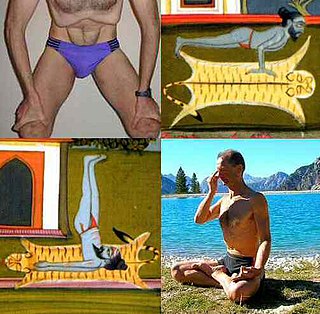

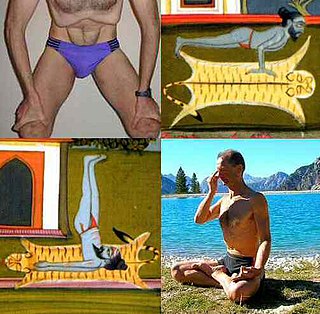

Yoga is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as practiced in the Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist traditions.

Kundalini yoga is a spiritual practice in the yogic and tantric traditions of Hinduism, centered on awakening the kundalini energy. This energy, often symbolized as a serpent coiled at the root chakra at the base of the spine, is guided upward through the chakras until it reaches the crown chakra at the top of the head. This leads to the blissful state of samadhi, symbolizing the union of Shiva and Shakti. Most yoga schools use pranayama, meditation, and moral code observation to raise the kundalini.

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga that uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force", alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some hatha yoga style techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Hindu Sanskrit epics and Buddhism's Pali canon. The oldest dated text so far found to describe hatha yoga, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu. The oldest texts to use the terminology of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist. Hindu hatha yoga texts appear from the 11th century onward.

Sadhu, also spelled saddhu, is a religious ascetic, mendicant or any holy person in Hinduism and Jainism who has renounced the worldly life. They are sometimes alternatively referred to as yogi, sannyasi or vairagi.

Dattatreya, Dattā or Dattaguru, is a paradigmatic Sannyasi (monk) and one of the lords of yoga, venerated as a Hindu god. He is considered to be an avatar and combined form of the three Hindu gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, who are also collectively known as the Trimurti, and as the manifestation of Parabrahma, the supreme being, in texts such as the Bhagavata Purana, the Markandeya Purana, and the Brahmanda Purana, though stories about his birth and origin vary from text to text. Several Upanishads are dedicated to him, as are texts of the Vedanta-Yoga tradition in Hinduism. One of the most important texts of Hinduism, namely Avadhuta Gita is attributed to Dattatreya. Over time, Dattatreya has inspired many monastic movements in Shaivism, Vaishnavism, and Shaktism, particularly in the Deccan region of India, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himalayan regions where Shaivism is prevalent. His pursuit of simple life, kindness to all, sharing of his knowledge and the meaning of life during his travels is reverentially mentioned in the poems by Tukaram, a saint-poet of the Bhakti movement.

The yamas, and their complement, the niyamas, represent a series of "right living" or ethical rules within Yoga philosophy. The word yama means "reining in" or "control". They are restraints for proper conduct given in the Vedas and the Yoga Sutras as moral imperatives, commandments, rules or goals. The yamas are a "don't"s list of self-restraints, typically representing commitments that affect one's relations with others and self. The complementary niyamas represent the "do"s. Together yamas and niyamas are personal obligations to live well.

Natha, also called Nath, are a Shaiva sub-tradition within Hinduism in India and Nepal. A medieval movement, it combined ideas from Buddhism, Shaivism and Yoga traditions of the Indian subcontinent. The Naths have been a confederation of devotees who consider Shiva as their first lord or guru, with varying lists of additional gurus. Of these, the 9th or 10th century Matsyendranatha and the ideas and organization mainly developed by Gorakhnath are particularly important. Gorakhnath is considered the originator of the Nath Panth.

Sahaja means spontaneous enlightenment in Indian and Tibetan Buddhist spirituality. Sahaja practices first arose in Bengal during the 8th century among yogis called Sahajiya siddhas.

A matha, also written as math, muth, mutth, mutt, or mut, is a Sanskrit word that means 'institute or college', and it also refers to a monastery in Hinduism. An alternative term for such a monastery is adheenam. The earliest epigraphical evidence for mathas related to Hindu-temples comes from the 7th to 10th century CE.

Matsyendranātha, also known as Matsyendra, Macchindranāth, Mīnanātha and Minapa was a saint and yogi in a number of Buddhist and Hindu traditions. He is considered the revivalist of hatha yoga as well as the author of some of its earliest texts. He is also seen as the founder of the natha sampradaya, having received the teachings from Shiva. He is associated with Kaula Shaivism. He is also one of the eighty-four mahasiddhas and considered the guru of Gorakshanath, another known figure in early hatha yoga. He is revered by both Hindus and Buddhists and is sometimes regarded as an incarnation of Avalokiteśvara.

A yogini is a female master practitioner of tantra and yoga, as well as a formal term of respect for female Hindu or Buddhist spiritual teachers in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Greater Tibet. The term is the feminine Sanskrit word of the masculine yogi, while the term "yogin" IPA:[ˈjoːɡɪn] is used in neutral, masculine or feminine sense.

Gorakhnath was a Hindu yogi, mahasiddha and saint who was the founder of the Nath Hindu monastic movement in India. He is considered one of the two disciples of Matsyendranath. His followers are known as Jogi, Gorakhnathi, Darshani or Kanphata.

Maithuna is a Sanskrit term for sexual intercourse within Tantra, or alternatively for the sexual fluids generated or the couple participating in the ritual. It is the most important of the Panchamakara and constitutes the main part of the grand ritual of Tantra also known as Tattva Chakra. Maithuna means the union of opposing forces, underlining the nonduality between human and divine, as well as worldly enjoyment (kama) and spiritual liberation (moksha). Maithuna is a popular icon in ancient Hindu art, portrayed as a couple engaged in physical loving.

The Yoga Yajnavalkya is a classical Hindu yoga text in the Sanskrit language. The text is written in the form of a male-female dialogue between the sage Yajnavalkya and Gargi. The text consists of 12 chapters and contains 504 verses.

Yogi Nath is a Shaivism-related group of monks which emerged around the 13th-century. They are sometimes called Jogi or simply Yogi, and are known for a variety of siddha yoga practices.

The Yoga-kundalini Upanishad, also called Yogakundali Upanishad, is a minor Upanishad of Hinduism. The Sanskrit text is one of the 20 Yoga Upanishads and is one of 32 Upanishads attached to the Krishna Yajurveda. In the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman, it is listed at number 86 in the anthology of 108 Upanishads.

David Gordon White is an American Indologist and author on the history of yoga and tantra. He won the CHOICE book selection in religion, and an honorable mention in the PROSE book awards, both for Sinister Yogis.