Haṭha yoga is a branch of yoga which uses physical techniques to preserve and channel the vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force" thus alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some haṭha yoga style techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Hindu Sanskrit epics and Buddhism's Pali canon. The oldest dated text so far found to describe haṭha yoga, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu. The oldest texts to use the terminology of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist. Hindu hatha yoga texts appear from the 11th century onwards.

A mudra is a symbolic or ritual gesture or pose in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism. While some mudras involve the entire body, most are performed with the hands and fingers.

The Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā is a classic fifteenth-century Sanskrit manual on haṭha yoga, written by Svātmārāma, who connects the teaching's lineage to Matsyendranath of the Nathas. It is among the most influential surviving texts on haṭha yoga, being one of the three classic texts alongside the Gheranda Samhita and the Shiva Samhita.

Nāḍī is a term for the channels through which, in traditional Indian medicine and spiritual theory, the energies such as prana of the physical body, the subtle body and the causal body are said to flow. Within this philosophical framework, the nadis are said to connect at special points of intensity, the chakras. All nadis are said to originate from one of two centres; the heart and the kanda, the latter being an egg-shaped bulb in the pelvic area, just below the navel. The three principal nadis run from the base of the spine to the head, and are the ida on the left, the sushumna in the centre, and the pingala on the right. Ultimately the goal is to unblock these nadis to bring liberation.

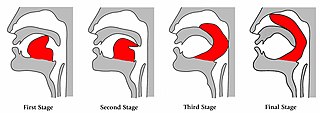

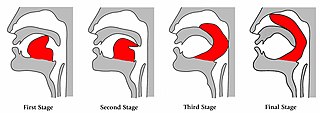

Khecarī mudrā is a hatha yoga practice carried out by curling the tip of the tongue back into the mouth until it reaches above the soft palate and into the nasal cavity. In the full practice, the tongue is made long enough to do this with many months of daily tongue stretching and by gradually severing the lingual frenulum with a sharp implement over a period of months.

The shatkarmas, also known as shatkriyas, are a set of Hatha yoga purifications of the body, to prepare for the main work of yoga towards moksha (liberation). These practices, outlined by Svatmarama in the Haṭha Yoga Pradīpikā as kriya, are Netī, Dhautī, Naulī, Basti, Kapālabhātī, and Trāṭaka. The Haṭha Ratnavali mentions two additional purifications, Cakri and Gajakarani, criticising the Hatha Yoga Pradipika for only describing the other six.

Kumbhaka is the retention of the breath in the yoga practice of pranayama. It has two types, accompanied whether after inhalation or after exhalation, and, the ultimate aim, unaccompanied. That state is kevala kumbhaka, the complete suspension of the breath for as long as the practitioner wishes.

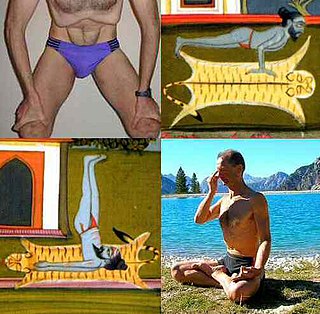

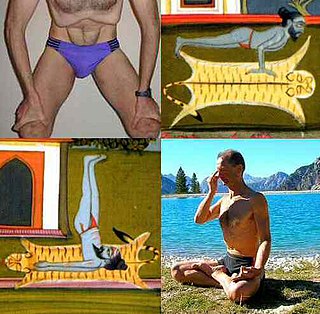

Nauli is one of the kriyas or shatkarmas, preliminary purifications, used in yoga. The exercise is claimed to serve the cleaning of the abdominal region and is based on a massage of the internal belly organs by a circular movement of the abdominal muscles. It is performed standing with the feet apart and the knees bent.

Viparita Karani or legs up the wall pose is both an asana and a mudra in hatha yoga. In modern yoga as exercise, it is commonly a fully supported pose using a wall and sometimes a pile of blankets.

Mahamudra is a hatha yoga gesture (mudra) whose purpose is to improve control over the sexual potential. The sexual potential, associated with apana, is essential in the process of awakening of the dormant spiritual energy (Kundalini) and attaining of spiritual powers (siddhi).

The Haṭha Ratnāvalī is a Haṭha yoga text written in the 17th century by Srinivasa. It is one of the first texts to name 84 asanas, earlier texts having claimed as many without naming them. It describes 36 asanas.

The Joga Pradīpikā is a hatha yoga text by Ramanandi Jayatarama written in 1737 in a mixture of Hindi, Braj Bhasa, Khari Boli and forms close to Sanskrit. It presents 6 cleansing methods, 84 asanas, 24 mudras and 8 kumbhakas. The text is illustrated in an 1830 manuscript with 84 paintings of asanas, prepared about a hundred years after the text.

Gorakshasana is a seated asana in hatha yoga. It has been used for meditation and in tantric practice.

The Vimānārcanākalpa is a 10th to 11th century text on Hatha yoga, attributed to the sage Marichi.

Vajroli mudra, the Vajroli Seal, is a practice in Hatha yoga which requires the yogin to preserve his semen, either by learning not to release it, or if released by drawing it up through his urethra from the vagina of "a woman devoted to the practice of yoga".

The Amṛtasiddhi, written in a Buddhist environment in about the 11th century, is the earliest substantial text on what became haṭha yoga, though it does not mention the term. The work describes the role of bindu in the yogic body, and how to control it using the Mahamudra so as to achieve immortality (Amṛta). The text has Buddhist features, and makes use of metaphors from alchemy.

The Vivekamārtaṇḍa is an early Hatha yoga text, the first to combine tantric and ascetic yoga. Attributed to Goraknath, it was probably written in the 13th century. It emphasises mudras as the most important practice. The name means "Sun of Discernment". It teaches khecarīmudrā, mahāmudrā, viparītakaraṇī and the three bandhas. It teaches six chakras and the raising of Kundalinī by means of "fire yoga" (vahniyogena).

The Amaraugha Prabodha is a 12th century Sanskrit text on hatha yoga, attributed to Gorakshanath. Its close connection with a Vajrayana text, the Amritasiddhi, implies a Buddhist origin for the practice of hatha yoga.

The Yogabīja is an early Haṭha yoga text, from around the 14th century. It was the first text to propose the derivation of haṭha from the Sanskrit words for sun and moon, with multiple esoteric interpretations.

The Gorakṣaśataka is an early text on Haṭha yoga text from the 13th century, attributed to the sage Gorakṣa. It was the first to teach a technique for raising Kundalini called "the stimulation of Sarasvati", along with elaborate pranayama, breath control. It was written for an audience of ascetics.