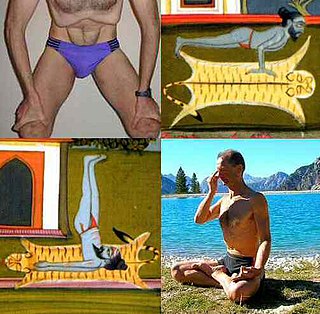

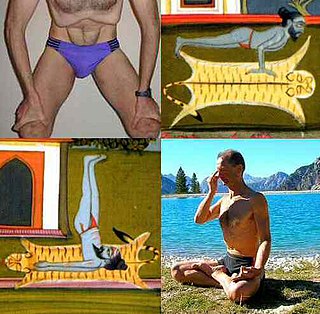

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga that uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force", alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some hatha yoga style techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Hindu Sanskrit epics and Buddhism's Pali canon. The oldest dated text so far found to describe hatha yoga, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu. The oldest texts to use the terminology of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist. Hindu hatha yoga texts appear from the 11th century onward.

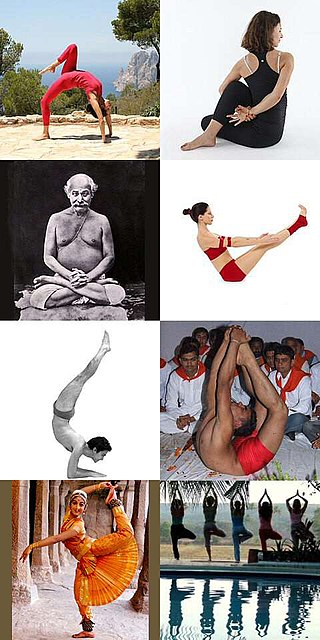

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

Yoga as therapy is the use of yoga as exercise, consisting mainly of postures called asanas, as a gentle form of exercise and relaxation applied specifically with the intention of improving health. This form of yoga is widely practised in classes, and may involve meditation, imagery, breath work (pranayama) and calming music as well as postural yoga.

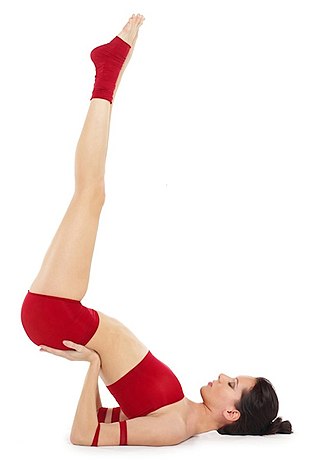

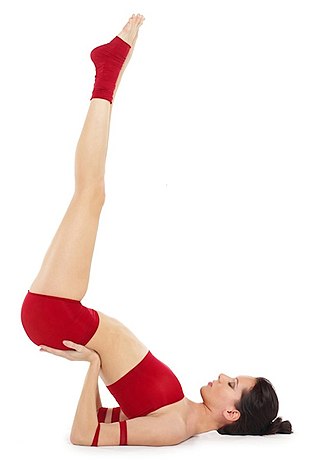

Sarvangasana, Shoulder stand, or more fully Salamba Sarvangasana, is an inverted asana in modern yoga as exercise; similar poses were used in medieval hatha yoga as a mudra.

Viparita Karani or legs up the wall pose is both an asana and a mudra in hatha yoga. In modern yoga as exercise, it is commonly a fully supported pose using a wall and sometimes a pile of blankets, where it is considered a restful practice. As a mudra it was practised using any preferred inversion, such as a headstand or shoulderstand. The purpose of the mudra was to reverse the downward flow of vital fluid being lost from the head, using gravity.

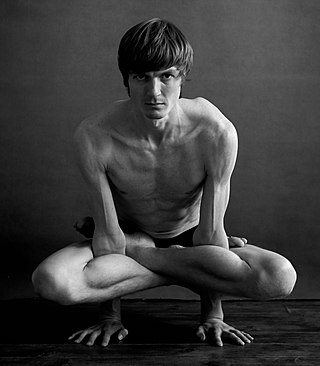

Virasana or Hero Pose is a kneeling asana in modern yoga as exercise. Medieval hatha yoga texts describe a cross-legged meditation asana under the same name. Supta Virasana is the reclining form of the pose; it provides a stronger stretch.

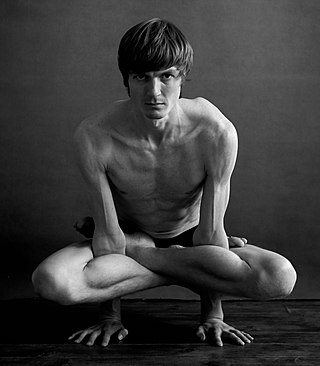

Kukkutasana, Cockerel Pose, or Rooster Posture is an arm-balancing asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, derived from the seated Padmasana, lotus position. It is one of the oldest non-seated asanas. Similar hand-balancing poses known from the 20th century include Pendant Pose or Lolasana, and Scale Pose or Tulasana.

Sir James Mallinson, 5th Baronet, of Walthamstow is a British Indologist, writer and translator. He is Boden Professor of Sanskrit at the University of Oxford, and recognised as one of the world's leading experts on the history of medieval Hatha yoga.

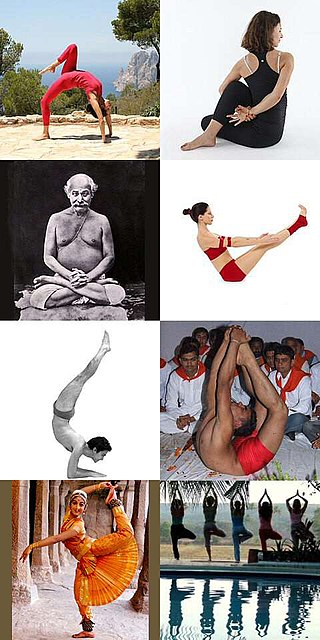

Modern yoga is a wide range of yoga practices with differing purposes, encompassing in its various forms yoga philosophy derived from the Vedas, physical postures derived from Hatha yoga, devotional and tantra-based practices, and Hindu nation-building approaches.

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures, often connected by flowing sequences, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises, and frequently ending with relaxation lying down or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in the US and Europe. It is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, which made use of similar postures, but it is generally simply called "yoga". Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including modern postural yoga and transnational anglophone yoga.

Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice is a 2010 book on yoga as exercise by the yoga scholar Mark Singleton. It is based on his PhD thesis, and argues that the yoga known worldwide is, in large part, a radical break from hatha yoga tradition, with different goals, and an unprecedented emphasis on asanas, many of them acquired in the 20th century. By the 19th century, the book explains, asanas and their ascetic practitioners were despised, and the yoga that Vivekananda brought to the West in the 1890s was asana-free. Yet, from the 1920s, an asana-based yoga emerged, with an emphasis on its health benefits, and flowing sequences (vinyasas) adapted from the gymnastics of the physical culture movement. This was encouraged by Indian nationalism, with the desire to present an image of health and strength.

Hatha Yoga: The Report of a Personal Experience is a 1943 book by Theos Casimir Bernard describing what he learnt of hatha yoga, ostensibly in India. It is one of the first books in English to describe and illustrate a substantial number of yoga poses (asanas); it describes the yoga purifications (shatkarmas), yoga breathing (pranayama), yogic seals (mudras), and meditative union (samadhi) at a comparable level of detail.

The Path of Modern Yoga: The History of an Embodied Spiritual Practice is a 2016 history of the modern practice of postural yoga by the yoga scholar Elliott Goldberg. It focuses in detail on eleven pioneering figures of the transformation of yoga in the 20th century, including Yogendra, Kuvalayananda, Pant Pratinidhi, Krishnamacharya, B. K. S. Iyengar and Indra Devi.

Modern yoga as exercise has often been taught by women to classes consisting mainly of women. This continued a tradition of gendered physical activity dating back to the early 20th century, with the Harmonic Gymnastics of Genevieve Stebbins in the US and Mary Bagot Stack in Britain. One of the pioneers of modern yoga, Indra Devi, a pupil of Krishnamacharya, popularised yoga among American women using her celebrity Hollywood clients as a lever.

Roots of Yoga is a 2017 book of commentary and translations from over 100 ancient and medieval yoga texts, mainly written in Sanskrit but including several other languages, many not previously published, about the origins of yoga including practices such as āsana, mantra, and meditation, by the scholar-practitioners James Mallinson and Mark Singleton.

The standing asanas are the yoga poses or asanas with one or both feet on the ground, and the body more or less upright. They are among the most distinctive features of modern yoga as exercise. Until the 20th century there were very few of these, the best example being Vrikshasana, Tree Pose. From the time of Krishnamacharya in Mysore, many standing poses have been created. Two major sources of these asanas have been identified: the exercise sequence Surya Namaskar ; and the gymnastics widely practised in India at the time, based on the prevailing physical culture.

Yoga in Britain is the practice of yoga, including modern yoga as exercise, in Britain. Yoga, consisting mainly of postures (asanas), arrived in Britain early in the 20th century, though the first classes that contained asanas were described as exercise systems for women rather than yoga. Classes called yoga, again mainly for women, began in the 1960s. Yoga grew further with the help of television programmes and the arrival of major brands including Iyengar Yoga and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.

Postural yoga began in India as a variant of traditional yoga, which was a mainly meditational practice; it has spread across the world and returned to the Indian subcontinent in different forms. The ancient Yoga Sutras of Patanjali mention yoga postures, asanas, only briefly, as meditation seats. Medieval Haṭha yoga made use of a small number of asanas alongside other techniques such as pranayama, shatkarmas, and mudras, but it was despised and almost extinct by the start of the 20th century. At that time, the revival of postural yoga was at first driven by Indian nationalism. Advocates such as Yogendra and Kuvalayananda made yoga acceptable in the 1920s, treating it as a medical subject. From the 1930s, the "father of modern yoga" Krishnamacharya developed a vigorous postural yoga, influenced by gymnastics, with transitions (vinyasas) that allowed one pose to flow into the next.

Gurus of Modern Yoga is an edited 2014 collection of essays on some of the gurus (leaders) of modern yoga by the yoga scholars Mark Singleton and Ellen Goldberg.