Charles Atlas was an American bodybuilder best remembered as the developer of a bodybuilding method and its associated exercise program which spawned a landmark advertising campaign featuring his name and likeness; it has been described as one of the longest-lasting and most memorable ad campaigns of all time.

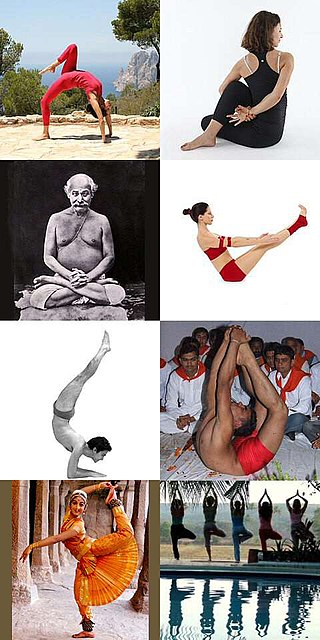

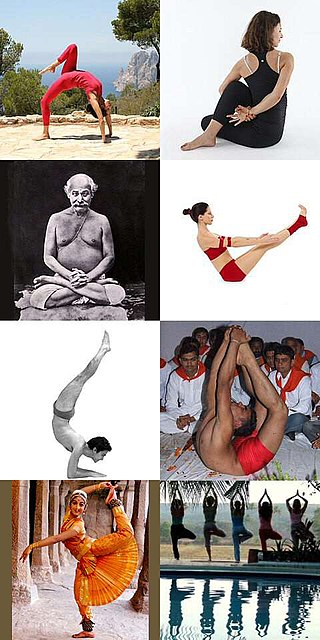

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

Naked yoga is the practice of yoga without clothes. It has existed since ancient times as a spiritual practice, and is mentioned in the 7th-10th century Bhagavata Purana and by the Ancient Greek geographer Strabo.

Bernarr Macfadden was an American proponent of physical culture, a combination of bodybuilding with nutritional and health theories. He founded the long-running magazine publishing company Macfadden Publications.

The Aphrodite of Knidos was an Ancient Greek sculpture of the goddess Aphrodite created by Praxiteles of Athens around the 4th century BC. It was one of the first life-sized representations of the nude female form in Greek history, displaying an alternative idea to male heroic nudity. Praxiteles' Aphrodite was shown nude, reaching for a bath towel while covering her pubis, which, in turn leaves her breasts exposed. Up until this point, Greek sculpture had been dominated by male nude figures. The original Greek sculpture is no longer in existence; however, many Roman copies survive of this influential work of art. Variants of the Venus Pudica are the Venus de' Medici and the Capitoline Venus.

Benedict Lust was a German-American who was one of the founders of naturopathic medicine in the first decades of the twentieth century.

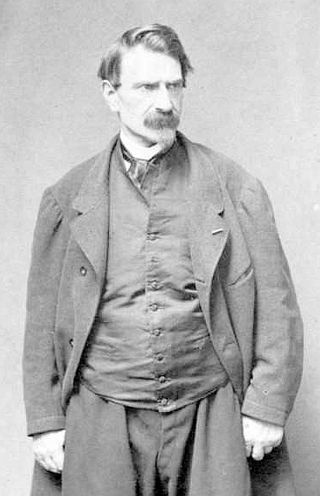

François Alexandre Nicolas Chéri Delsarte was a French singer, orator, and coach. Though he achieved some success as a composer, he is chiefly known as a teacher in singing and declamation (oratory).

Milo Milton Hastings was an American inventor, author, and nutritionist. He invented the forced-draft chicken incubator and Weeniwinks, a health-food snack. He wrote about chickens, science fiction, and health, among other things. Some of his writing is available in book form and on Project Gutenberg. Hastings was married twice and had three children.

Adolf Karl Hubert Koch was a German educationalist and sports teacher. He was the founder of a gymnastics movement named after him and a pioneer of the Freikörperkultur movement in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, which in turn was part of the larger Lebensreform movement.

Yoga Journal is a website and digital journal, formerly a print magazine, on yoga as exercise founded in California in 1975 with the goal of combining the essence of traditional yoga with scientific understanding. It has produced live events and materials such as DVDs on yoga and related subjects.

Lotte Herrlich (1883–1956) was a German photographer. She is regarded as the most important female photographer of the German naturism. This mainly was during the 1920s, in which the Freikörperkultur was popular within Germany, before the Nazi Party assumed power (1930s), promptly prohibiting it.

Yin Yoga is slow-paced style of yoga, incorporating principles of traditional Chinese medicine, with asanas (postures) that are held for longer periods of time than in other yoga styles. Advanced practitioners may stay in one asana for five minutes or more. As conceptualized in the Taoist and Dharmic traditions, the sequences of postures are meant to stimulate the channels of the subtle body, known as meridians in Chinese medicine and as nadis in Hatha yoga.

Genevieve Stebbins was an American author, teacher of her system of Harmonic Gymnastics and performer of the Delsarte system of expression. She published four books and was the founder of the New York School of Expression.

Gertrud Leistikow was a German dancer and choreographer. She is primarily associated with nude and Grotesque dance.

Bess Mensendieck was an American physician and gymnastics teacher of Dutch descent who developed the Mensendieck System, a therapeutic teaching methodology for female physical education claimed to be both corrective and preventive. She was one of the most important founders of early breathing and physical pedagogy in Europe and America.

Mary Bagot Stack, known as Mollie Bagot Stack, founded the Women's League of Health & Beauty in 1930, the first and most significant mass keep-fit system of the 1930s in the UK. This has continued as an exercise system into the 21st century.

The history of yoga in the United States begins in the 19th century, with the philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; Emerson's poem "Brahma" states the Hindu philosophy behind yoga. More widespread interest in yoga can be dated to the Hindu leader Vivekananda's visit from India in 1893; he presented yoga as a spiritual path without postures (asanas), very different from modern yoga as exercise. Two other early figures, however, the women's rights advocate Ida C. Craddock and the businessman and occultist Pierre Bernard, created their own interpretations of yoga, based on tantra and oriented to physical pleasure.

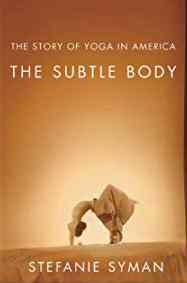

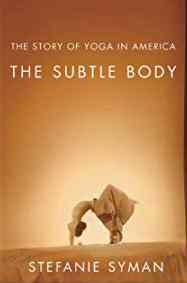

The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America is a 2010 book on the history of yoga as exercise by the American journalist Stefanie Syman. It spans the period from the first precursors of American yoga, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thoreau, the arrival of Vivekananda, the role of Hollywood with Indra Devi, the hippie generation, and the leaders of a revived but now postural yoga such as Bikram Choudhury and Pattabhi Jois.

John de Mirjian was an Armenian American glamour photographer based in New York, famous for his images of celebrities, sometimes in risque poses. His brother Arto de Mirjian continued the business after John's early death.

Carrica Le Favre was an American physical culturist, dress reform advocate and vegetarianism activist. She founded the Chicago Vegetarian Society and the New York Vegetarian Society.