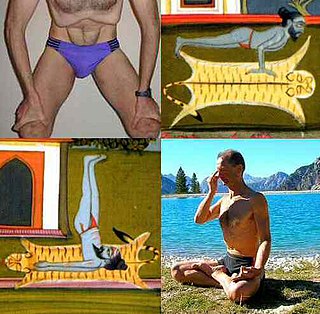

Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga that uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word हठ haṭha literally means "force", alluding to a system of physical techniques. Some hatha yoga style techniques can be traced back at least to the 1st-century CE, in texts such as the Hindu Sanskrit epics and Buddhism's Pali canon. The oldest dated text so far found to describe hatha yoga, the 11th-century Amṛtasiddhi, comes from a tantric Buddhist milieu. The oldest texts to use the terminology of hatha are also Vajrayana Buddhist. Hindu hatha yoga texts appear from the 11th century onward.

K. Pattabhi Jois was an Indian yoga guru who developed and popularized the flowing style of yoga as exercise known as Ashtanga vinyasa yoga. In 1948, Jois established the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute in Mysore, India. Pattabhi Jois is one of a short list of Indians instrumental in establishing modern yoga as exercise in the 20th century, along with B. K. S. Iyengar, another pupil of Krishnamacharya in Mysore. Jois sexually abused some of his yoga students by touching inappropriately during adjustments. Sharath Jois has publicly apologised for his grandfather's "improper adjustments".

Ashtanga vinyasa yoga is a style of yoga as exercise popularised by K. Pattabhi Jois during the twentieth century, often promoted as a dynamic form of classical Indian (hatha) yoga. Jois claimed to have learnt the system from his teacher Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. The style is energetic, synchronising breath with movements. The individual poses (asanas) are linked by flowing movements (vinyasas).

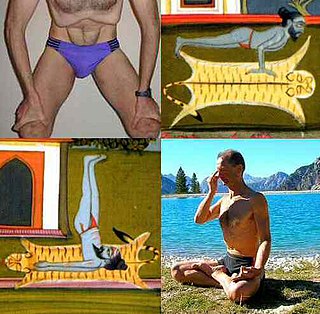

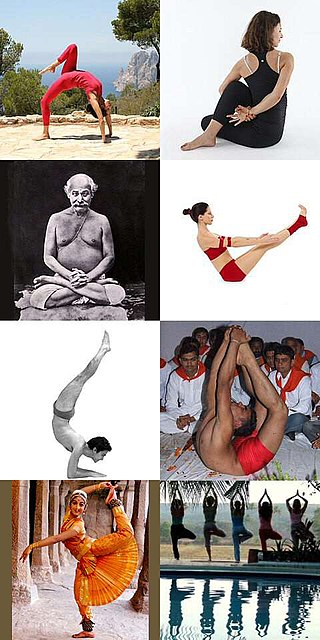

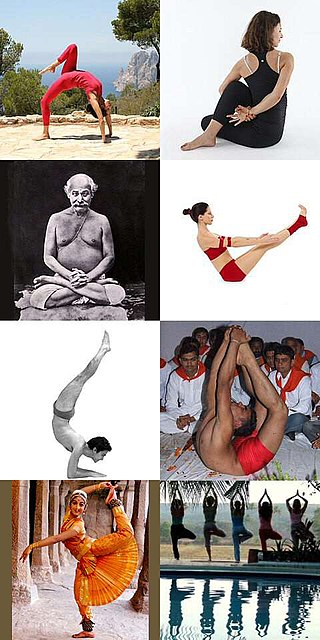

An āsana is a body posture, originally and still a general term for a sitting meditation pose, and later extended in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, to any type of position, adding reclining, standing, inverted, twisting, and balancing poses. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali define "asana" as "[a position that] is steady and comfortable". Patanjali mentions the ability to sit for extended periods as one of the eight limbs of his system. Asanas are also called yoga poses or yoga postures in English.

Sun Salutation, also called Surya Namaskar or Salute to the Sun, is a practice in yoga as exercise incorporating a flow sequence of some twelve linked asanas. The asana sequence was first recorded as yoga in the early 20th century, though similar exercises were in use in India before that, for example among wrestlers. The basic sequence involves moving from a standing position into Downward and Upward Dog poses and then back to the standing position, but many variations are possible. The set of 12 asanas is dedicated to the Hindu solar deity, Surya. In some Indian traditions, the positions are each associated with a different mantra.

Downward Dog Pose or Downward-facing Dog Pose, also called Adho Mukha Svanasana, is an inversion asana, often practised as part of a flowing sequence of poses, especially Surya Namaskar, the Salute to the Sun. The asana is commonly used in modern yoga as exercise. The asana does not have formally named variations, but several playful variants are used to assist beginning practitioners to become comfortable in the pose.

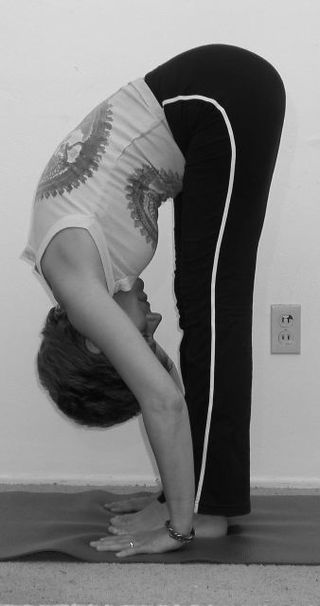

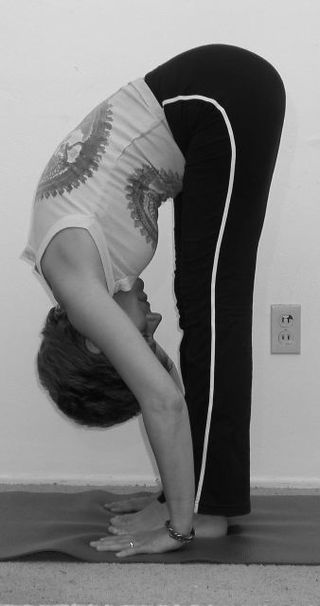

Uttanasana or Standing Forward Bend, with variants such as Padahastasana where the toes are grasped, is a standing forward bending asana in modern yoga as exercise.

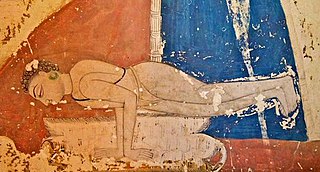

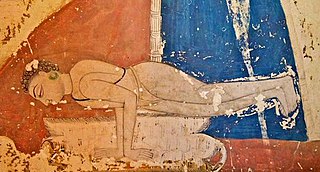

Shavasana, Corpse Pose, or Mritasana, is an asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise, often used for relaxation at the end of a session. It is the usual pose for the practice of yoga nidra meditation, and is an important pose in Restorative Yoga.

A vinyasa is a smooth transition between asanas in flowing styles of modern yoga as exercise such as Vinyasa Krama Yoga and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga, especially when movement is paired with the breath.

Virasana or Hero Pose is a kneeling asana in modern yoga as exercise. Medieval hatha yoga texts describe a cross-legged meditation asana under the same name. Supta Virasana is the reclining form of the pose; it provides a stronger stretch.

Mayūrāsana or Peacock pose is a hand-balancing asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise with the body held horizontal over the hands. It is one of the oldest non-seated asanas.

Kurmasana, Tortoise Pose, or Turtle Pose is a sitting forward bending asana in hatha yoga and modern yoga as exercise.

Norman E. Sjoman is known as author of the 1996 book The Yoga Tradition of the Mysore Palace, which contains an English translation of the yoga section of Sritattvanidhi, a 19th-century treatise by the Maharaja of Mysore, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III. This book contributes an original view on the history and development of the teaching traditions behind modern asanas. According to Sjoman, a majority of the tradition of teaching yoga as exercise, spread primarily through the teachings of B. K. S. Iyengar and his students, "appears to be distinct from the philosophical or textual tradition [of hatha yoga], and does not appear to have any basis as a [genuine] tradition as there is no textual support for the asanas taught and no lineage of teachers."

Modern yoga is a wide range of yoga practices with differing purposes, encompassing in its various forms yoga philosophy derived from the Vedas, physical postures derived from Hatha yoga, devotional and tantra-based practices, and Hindu nation-building approaches.

Yoga as exercise is a physical activity consisting mainly of postures, often connected by flowing sequences, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises, and frequently ending with relaxation lying down or meditation. Yoga in this form has become familiar across the world, especially in the US and Europe. It is derived from medieval Haṭha yoga, which made use of similar postures, but it is generally simply called "yoga". Academics have given yoga as exercise a variety of names, including modern postural yoga and transnational anglophone yoga.

Yoga Makaranda, meaning "Essence of Yoga", is a 1934 book on hatha yoga by the influential pioneer of yoga as exercise, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. Most of the text is a description of 42 asanas accompanied by 95 photographs of Krishnamacharya and his students executing the poses. There is a brief account of practices other than asanas, which form just one of the eight limbs of classical yoga, that Krishnamacharya "did not instruct his students to practice".

The standing asanas are the yoga poses or asanas with one or both feet on the ground, and the body more or less upright. They are among the most distinctive features of modern yoga as exercise. Until the 20th century there were very few of these, the best example being Vrikshasana, Tree Pose. From the time of Krishnamacharya in Mysore, many standing poses have been created. Two major sources of these asanas have been identified: the exercise sequence Surya Namaskar ; and the gymnastics widely practised in India at the time, based on the prevailing physical culture.

The history of yoga in the United States begins in the 19th century, with the philosophers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; Emerson's poem "Brahma" states the Hindu philosophy behind yoga. More widespread interest in yoga can be dated to the Hindu leader Vivekananda's visit from India in 1893; he presented yoga as a spiritual path without postures (asanas), very different from modern yoga as exercise. Two other early figures, however, the women's rights advocate Ida C. Craddock and the businessman and occultist Pierre Bernard, created their own interpretations of yoga, based on tantra and oriented to physical pleasure.

Yoga in Britain is the practice of yoga, including modern yoga as exercise, in Britain. Yoga, consisting mainly of postures (asanas), arrived in Britain early in the 20th century, though the first classes that contained asanas were described as exercise systems for women rather than yoga. Classes called yoga, again mainly for women, began in the 1960s. Yoga grew further with the help of television programmes and the arrival of major brands including Iyengar Yoga and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga.