| |

| Also known as | Silambattam, Chilambam, Chilambattam |

|---|---|

| Focus | Weapons |

| Hardness | Semi-contact |

| Country of origin | India |

| Olympic sport | No |

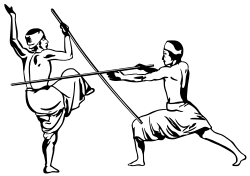

Silambam is an old Indian martial art originating in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu. [1] This style is mentioned in Tamil Sangam literature. [2] The World Silambam Association is the official international body of Silambam.