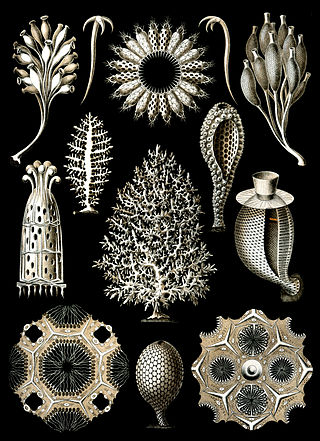

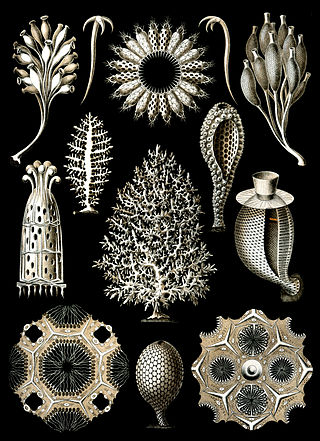

The calcareoussponges are members of the animal phylum Porifera, the cellular sponges. They are characterized by spicules made of calcium carbonate, in the form of high-magnesium calcite or aragonite. While the spicules in most species are triradiate, some species may possess two- or four-pointed spicules. Unlike other sponges, calcareans lack microscleres, tiny spicules which reinforce the flesh. In addition, their spicules develop from the outside-in, mineralizing within a hollow organic sheath.

Leucosolenida is an order of sponges in the class Calcarea and the subclass Calcaronea. Species in Leucosolenida are calcareous, with a skeleton composed exclusively of free spicules without calcified non-spicular reinforcements.

Minchinellidae is a family of calcareous sponges, members of the class Calcarea. It is the only family in the monotypic order Lithonida. The families Petrobionidae and Lepidoleuconidae have also sometimes been placed within Lithonida, though more recently they have been moved to the order Baerida. Thanks to their hypercalcified structure, minchinellids have a fossil record reaching as far back as the Jurassic Period.

Hexasterophora are a subclass of glass sponges in the class Hexactinellida. Most living hexasterophorans can be divided into three orders: Lyssacinosida, Lychniscosida, and Sceptrulophora. Like other glass sponges, hexasterophorans have skeletons composed of overlapping six-rayed spicules. In addition, they can be characterized by the presence of hexasters, a type of microsclere with six rays unfurling into multi-branched structures.

The Craniidae are a family of brachiopods, the only surviving members of the subphylum Craniiformea. They are the only members of the order Craniida, the monotypic suborder Craniidina, and the superfamily Cranioidea; consequently, the latter two taxa are at present redundant and rarely used.There are three living genera within Craniidae: Neoancistrocrania, Novocrania, and Valdiviathyris. As adults, craniids either live freely on the ocean floor or, more commonly, cement themselves onto a hard object with all or part of the ventral valve.

The taxonomy of commonly fossilized invertebrates combines both traditional and modern paleozoological terminology. This article compiles various invertebrate taxa in the fossil record, ranging from protists to arthropods. This includes groups that are significant in paleontological contexts, abundant in the fossil record, or have a high proportion of extinct species. Special notations are explained below:

Rhynchonelliformea is a major subphylum and clade of brachiopods. It is roughly equivalent to the former class Articulata, which was used previously in brachiopod taxonomy up until the 1990s. These so-called articulated brachiopods have many anatomical differences relative to "inarticulate" brachiopods of the subphyla Linguliformea and Craniformea. Articulates have hard calcium carbonate shells with tongue-and-groove hinge articulations and separate sets of simple opening and closing muscles.

Reticulosa is an extinct order of sea sponges in the class Hexactinellida and the subclass Amphidiscophora. Reticulosans were diverse in shape and size, similar to their modern relatives, the amphidiscosidans. Some were smooth and attached to a surface at a flat point, others were polyhedral or ornamented with nodes, many were covered in bristles, and a few were even suspended above the seabed by a rope-like anchor of braided glass spicules.

Discorbis is a genus of benthic Foraminifera, that made its first appearance during the Eocene. Its present distribution is cosmopolitan.

Paterinata is an extinct class of linguliform brachiopods which lived from the lower Cambrian ("Tommotian") to the Upper Ordovician (Hirnantian). It contains the single order Paterinida and the subfamily Paterinoidea. Despite being some of the earliest brachiopods to appear in the fossil record, paterinides stayed as a relatively subdued and low-diversity group even as other brachiopods diversified later in the Cambrian and Ordovician. Paterinides are notable for their high degree of convergent evolution with rhynchonelliform (articulate) brachiopods, which have a similar set of muscles and hinge-adjacent structures.

Trimerellida is an extinct order of craniate brachiopods, containing the sole superfamily Trimerelloidea and the families Adensuidae, Trimerellidae, and Ussuniidae. Trimerellidae was a widespread family of warm-water brachiopods ranging from the Middle Ordovician to the late Silurian (Ludlow). Adensuidae and Ussuniidae are monogeneric families restricted to the Ordovician of Kazakhstan. Most individuals were free-living, though some clustered into large congregations similar to modern oyster reefs.

Heteractinida is an extinct grade of Paleozoic (Cambrian–Permian) sponges, sometimes used as a class or order. They are most commonly considered paraphyletic with respect to Calcarea, though some studies instead argue that they are paraphyletic relative to Hexactinellida. Heteractinids can be distinguished by their six-pronged (snowflake-shaped) spicules, whose symmetry historically suggested a relationship with the triradial calcarean sponges.

TrilobitesLink, 1807 is a disused genus of trilobites, the species of which are now all assigned to other genera.

Craniopsidae is an extinct family of craniiform brachiopods which lived from the mid-Cambrian to the Lower Carboniferous (Tournaisian). It is the only family in the monotypic superfamily Craniopsoidea and the monotypic order Craniopsida. If one includes the ambiguous Cambrian genus Discinopsis, craniopsids were the first craniiforms to appear, and may be ancestral to craniids and trimerellides. An even earlier Cambrian genus, Heliomedusa, has sometimes been identified as a craniopsid. More recently, Heliomedusa has been considered a stem-group brachiopod related to Mickwitzia.

Kutorginates (Kutorginata) are an extinct class of early rhynchonelliform ("articulate") brachiopods. The class contains only a single order, Kutorginida (kutorginides). Kutorginides were among the earliest rhynchonelliforms, restricted to the lower-middle part of the Cambrian Period.

Amphidiscosida is an order of hexactinellids. The Amphidiscosida are commonly regarded as the only living sponges in the subclass Amphidiscophora.

Sceptrulophora is an order of hexactinellid sponges. They are characterized by sceptrules, a type of microsclere with a single straight rod terminating at a bundle of spines or knobs. An anchor- or nail-shaped sceptrule is called a clavule. A fork-shaped sceptrule, ending at a few large tines, is called a scopule. A broom-shaped sceptrule, ending at many small bristles, is called a sarule.

Sphaerocoeliidae is an extinct family of calcareous sponges, the only family in the monotypic order Sphaerocoeliida. Sphaerocoeliids are one of several unrelated sponge groups described as "sphinctozoans", with a distinctive multi-chambered body structure. Sphaerocoeliids persisted from the Permian to the Cenomanian stage of the Cretaceous, a longer period of time than most other "sphinctozoans". Sphaerocoeliids make up the majority of calcareous "sphinctozoans", as well as a large portion of post-Triassic "sphinctozoan" diversity. "Sphinctozoans" and the similar "inozoans" were historically grouped together in the polyphyletic order Pharetronida.

Stellispongiida is an order of calcareous sponges, most or all of which are extinct. Stellispongiids are one of several unrelated sponge groups described as "inozoans", a name referring to sponges with a hypermineralized calcitic skeleton independent from their spicules. Stellispongiids have a solid skeleton encasing calcite spicules arranged in trabeculae. "Inozoans" and the similar "sphinctozoans" were historically grouped together in the polyphyletic order Pharetronida.

Hemidiscellidae is an extinct family of sponges in the class Hexactinellida and the subclass Amphidiscophora. Hemidiscellidae is the only family in the order Hemidiscosa.