African horse sickness (AHS) is a highly infectious and often fatal disease caused by African horse sickness virus. It commonly affects horses, mules, and donkeys. It is caused by a virus of the genus Orbivirus belonging to the family Reoviridae. This disease can be caused by any of the nine serotypes of this virus. AHS is not directly contagious, but is known to be spread by insect vectors.

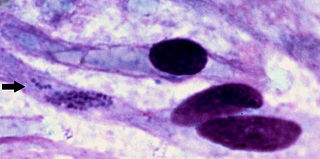

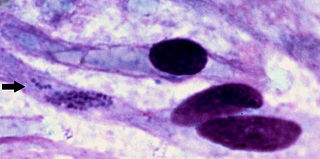

Cytauxzoon felis is a protozoal organism transmitted to domestic cats by tick bites, and whose natural reservoir host is the bobcat. C. felis has been found in other wild felid species such as the cougar, as well as a white tiger in captivity. C. felis infection is limited to the family Felidae which means that C. felis poses no zoonotic risk or agricultural risk. Until recently it was believed that after infection with C. felis, pet cats almost always died. As awareness of C. felis has increased it has been found that treatment is not always futile. More cats have been shown to survive the infection than was previously thought. New treatments offer as much as 60% survival rate.

Babesia, also called Nuttallia, is an apicomplexan parasite that infects red blood cells and is transmitted by ticks. Originally discovered by Romanian bacteriologist Victor Babeș in 1888; over 100 species of Babesia have since been identified.

Lumpy skin disease (LSD) is an infectious disease in cattle caused by a virus of the family Poxviridae, also known as Neethling virus. The disease is characterized by fever, enlarged superficial lymph nodes, and multiple nodules on the skin and mucous membranes, including those of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Infected cattle may also develop edematous swelling in their limbs and exhibit lameness. The virus has important economic implications since affected animals tend to have permanent damage to their skin, lowering the commercial value of their hide. Additionally, the disease often results in chronic debility, reduced milk production, poor growth, infertility, abortion, and sometimes death.

Bovine leukemia virus (BLV) is a retrovirus which causes enzootic bovine leukosis in cattle. It is closely related to the human T‑lymphotropic virus type 1 (HTLV-I). BLV may integrate into the genomic DNA of B‑lymphocytes as a DNA intermediate, or exist as unintegrated circular or linear forms. Besides structural and enzymatic genes required for virion production, BLV expresses the Tax protein and microRNAs involved in cell proliferation and oncogenesis. In cattle, most infected animals are asymptomatic; leukemia is rare, but lymphoproliferation is more frequent (30%).

Theileria is a genus of parasites that belongs to the phylum Apicomplexa, and is closely related to Plasmodium. Two Theileria species, T. annulata and T. parva, are important cattle parasites. T. annulata causes tropical theileriosis and T. parva causes East Coast fever. Theileria species are transmitted by ticks. The genomes of T. orientalis Shintoku, Theileria equi WA, Theileria annulata Ankara and Theileria parva Muguga have been sequenced and published.

Epizootic lymphangitis is a contagious lymphangitis disease of horses and mules caused by the fungus Histoplasma farciminosum. Cattle are also susceptible, but more resistant to the disease than equids.

East Coast fever, also known as theileriosis, is a disease of cattle which occurs in Africa and is caused by the protozoan parasite Theileria parva. The primary vector which spreads T. parva between cattle is a tick, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. East Coast fever is of major economic importance to livestock farmers in Africa, killing at least one million cattle each year. The disease occurs in Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Zambia. In 2003, East Coast fever was introduced to Comoros by cattle imported from Tanzania. It has been eradicated in South Africa.

Heartwater is a tick-borne rickettsial disease. The name is derived from the fact that fluid can collect around the heart or in the lungs of infected animals. It is caused by Ehrlichia ruminantium —an intracellular Gram-negative coccal bacterium. The disease is spread by various Amblyomma ticks, and has a large economic impact on cattle production in affected areas. There are four documented manifestations of the disease, these are acute, peracute, subacute, and a mild form known as heartwater fever. There are reports of zoonotic infections of humans by E. ruminantium, similar to other Ehrlichia species, such as those that cause human ehrlichiosis.

Rhipicephalus is a genus of ticks in the family Ixodidae, the hard ticks, consisting of about 74 or 75 species. Most are native to tropical Africa.

The Asian blue tick is an economically important tick that parasitises a variety of livestock and wild mammal species, especially cattle, on which it is the most economically significant ectoparasite in the world. It is known as the Australian cattle tick, southern cattle tick, Cuban tick, Madagascar blue tick, and Puerto Rican Texas fever tick.

Babesia bovis is an Apicomplexan single-celled parasite of cattle which occasionally infects humans. The disease it and other members of the genus Babesia cause is a hemolytic anemia known as babesiosis and colloquially called Texas cattle fever, redwater or piroplasmosis. It is transmitted by bites from infected larval ticks of the order Ixodida. It was eradicated from the United States by 1943, but is still present in Mexico and much of the world's tropics. The chief vector of Babesia species is the southern cattle fever tick Rhipicephalus microplus.

Theileria parva is a species of parasites, named in honour of Arnold Theiler, that causes East Coast fever (theileriosis) in cattle, a costly disease in Africa. The main vector for T. parva is the tick Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Theiler found that East Coast fever was not the same as redwater, but caused by a different protozoan.

Ticks of domestic animals directly cause poor health and loss of production to their hosts. Ticks also transmit numerous kinds of viruses, bacteria, and protozoa between domestic animals. These microbes cause diseases which can be severely debilitating or fatal to domestic animals, and may also affect humans. Ticks are especially important to domestic animals in tropical and subtropical countries, where the warm climate enables many species to flourish. Also, the large populations of wild animals in warm countries provide a reservoir of ticks and infective microbes that spread to domestic animals. Farmers of livestock animals use many methods to control ticks, and related treatments are used to reduce infestation of companion animals.

Anaplasma bovis is gram negative, obligate intracellular organism, which can be found in wild and domestic ruminants, and potentially a wide variety of other species. It is one of the last species of the Family Anaplasmaceae to be formally described. It preferentially infects host monocytes, and is often diagnosed via blood smears, PCR, and ELISA. A. bovis is not currently considered zoonotic, and does not frequently cause serious clinical disease in its host. This organism is transmitted by tick vectors, so tick bite prevention is the mainstay of A. bovis control, although clinical infections can be treated with tetracyclines. This organism has a global distribution, with infections noted in many areas, including Korea, Japan, Europe, Brazil, Africa, and North America.

Hyalomma dromedarii is a species of hard-bodied ticks belonging to the family Ixodidae.

The zebra tick or yellow back tick is a species of hard tick. It is common in the Horn of Africa, with a habitat of the Rift Valley and eastward. It feeds upon a wide variety of species, including livestock, wild mammals, and humans, and can be a vector for various pathogens. The adult male has a distinctive black and ivory ornamentation on its scutum.

Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, the brown ear tick, is a hard tick found in Africa where it spreads the parasite Theileria parva, the cause of East Coast fever in cattle. The tick has a three-host life-cycle, spending around 10% of its life feeding on animals. The most common host species include buffalo, cattle, and large antelope, but R. appendiculatus is also found on other animals, such as hares, dogs, and warthogs.