Canine distemper virus (CDV) is a viral disease that affects a wide variety of mammal families, including domestic and wild species of dogs, coyotes, foxes, pandas, wolves, ferrets, skunks, raccoons, and felines, as well as pinnipeds, some primates, and a variety of other species. CDV does not affect humans.

Bordetella is a genus of small, Gram-negative, coccobacilli bacteria of the phylum Pseudomonadota. Bordetella species, with the exception of B. petrii, are obligate aerobes, as well as highly fastidious, or difficult to culture. All species can infect humans. The first three species to be described are sometimes referred to as the 'classical species'. Two of these are also motile.

The National Association of State Public Health Veterinarians (NASPHV) develops and publishes uniform public health procedures involving zoonotic disease in the United States and its territories. These veterinarians work closely with emergency rooms, legislators, local officials, schools, health departments, and the general public to prevent disease exposure and control diseases that are transmitted to humans from animals and animal products.

Kennel cough is an upper respiratory infection affecting dogs. There are multiple causative agents, the most common being the bacterium Bordetella bronchiseptica, followed by canine parainfluenza virus, and to a lesser extent canine coronavirus. It is highly contagious; however, adult dogs may display immunity to reinfection even under constant exposure. Kennel cough is so named because the infection can spread quickly among dogs in the close quarters of a kennel or animal shelter.

Carnivore protoparvovirus 1 is a species of parvovirus that infects carnivorans. It causes a highly contagious disease in both dogs and cats separately. The disease is generally divided into two major genogroups: FPV containing the classical feline panleukopenia virus (FPLV), and CPV-2 containing the canine parvovirus type 2 (CPV-2) which appeared in the 1970s.

The health of dogs is a well studied area in veterinary medicine.

Canine parvovirus is a contagious virus mainly affecting dogs and wolves. CPV is highly contagious and is spread from dog to dog by direct or indirect contact with their feces. Vaccines can prevent this infection, but mortality can reach 91% in untreated cases. Treatment often involves veterinary hospitalization. Canine parvovirus often infects other mammals including foxes, cats, and skunks. Felines (cats) are also susceptible to panleukopenia, a different strain of parvovirus.

Canine influenza is influenza occurring in canine animals. Canine influenza is caused by varieties of influenzavirus A, such as equine influenza virus H3N8, which was discovered to cause disease in canines in 2004. Because of the lack of previous exposure to this virus, dogs have no natural immunity to it. Therefore, the disease is rapidly transmitted between individual dogs. Canine influenza may be endemic in some regional dog populations of the United States. It is a disease with a high morbidity but a low incidence of death.

Pneumonia is an irritation of the lungs caused by different sources. It is characterized by an inflammation of the deep lung tissues and the bronchi. Pneumonia can be acute or chronic. This life-threatening illness is more common in cats than in dogs and the complication “Kennel Cough” can occur in young pets.

Veterinary dentistry involves the application of dental care to animals, encompassing not only the prevention of diseases and maladies of the mouth, but also considers treatment. In the United States, veterinary dentistry is one of 20 veterinary specialties recognized by the American Veterinary Medical Association.

A vaccine-associated sarcoma (VAS) or feline injection-site sarcoma (FISS) is a type of malignant tumor found in cats which has been linked to certain vaccines. VAS has become a concern for veterinarians and cat owners alike and has resulted in changes in recommended vaccine protocols. These sarcomas have been most commonly associated with rabies and feline leukemia virus vaccines, but other vaccines and injected medications have also been implicated.

The health of domestic cats is a well studied area in veterinary medicine.

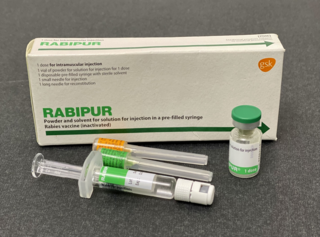

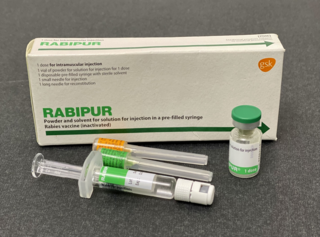

The rabies vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rabies. There are several rabies vaccines available that are both safe and effective. Vaccinations must be administered prior to rabies virus exposure or within the latent period after exposure to prevent the disease. Transmission of rabies virus to humans typically occurs through a bite or scratch from an infectious animal, but exposure can occur through indirect contact with the saliva from an infectious individual.

Feline vaccination is animal vaccination applied to cats. Vaccination plays a vital role in protecting cats from infectious diseases, some of which are potentially fatal. They can be exposed to these diseases from their environment, other pets, or even humans.

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia because its victims would panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abnormal sensations at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, violent movements, uncontrolled excitement, fear of water, an inability to move parts of the body, confusion, and loss of consciousness. Once symptoms appear, the result is virtually always death. The time period between contracting the disease and the start of symptoms is usually one to three months but can vary from less than one week to more than one year. The time depends on the distance the virus must travel along peripheral nerves to reach the central nervous system.

The prevalence of rabies, a deadly viral disease affecting mammals, varies significantly across regions worldwide, posing a persistent public health problem.

A vaccine-preventable disease is an infectious disease for which an effective preventive vaccine exists. If a person acquires a vaccine-preventable disease and dies from it, the death is considered a vaccine-preventable death.

ATCvet code QI07Immunologicals for Canidae is a therapeutic subgroup of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System for veterinary medicinal products, a system of alphanumeric codes developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the classification of drugs and other medical products for veterinary use. Subgroup QI07 is part of the anatomical group QI Immunologicals.

DA2PP is a multivalent vaccine for dogs that protects against the viruses indicated by the alphanumeric characters forming the abbreviation: D for canine distemper, A2 for canine adenovirus type 2, which offers cross-protection to canine adenovirus type 1, the first P for canine parvovirus, and the second P for parainfluenza. Because infectious canine hepatitis is another name for canine adenovirus type 1, an H is sometimes used instead of A. In DA2PPC, the C indicates canine coronavirus. This is not considered a core vaccination and is therefore often excluded from the abbreviation.

Animal vaccination is the immunisation of a domestic, livestock or wild animal. The practice is connected to veterinary medicine. The first animal vaccine invented was for chicken cholera in 1879 by Louis Pasteur. The production of such vaccines encounter issues in relation to the economic difficulties of individuals, the government and companies. Regulation of animal vaccinations is less compared to the regulations of human vaccinations. Vaccines are categorised into conventional and next generation vaccines. Animal vaccines have been found to be the most cost effective and sustainable methods of controlling infectious veterinary diseases. In 2017, the veterinary vaccine industry was valued at US$7 billion and it is predicted to reach US$9 billion in 2024.