Related Research Articles

Lingua Franca Nova, abbreviated as LFN and known colloquially as elefen, is an auxiliary constructed language originally created by C. George Boeree of Shippensburg University, Pennsylvania, and further developed by many of its users. Its vocabulary is based on the Romance languages French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, and Catalan. Lingua Franca Nova has phonemic spelling based on 22 letters from the Latin script.

Sango is the primary language spoken in the Central African Republic and also the official language of the country. It is used as a lingua franca across the country and had 450,000 native speakers in 1988. It also has 1.6 million second language speakers.

The Bemba language, ChiBemba, is a Bantu language spoken primarily in north-eastern Zambia by the Bemba people and as a lingua franca by about 18 related ethnic groups, including the Bisa people of Mpika and Lake Bangweulu, and to a lesser extent in Katanga in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Tanzania. Including all its dialects, Bemba is the most spoken indigenous Bantu language and a lingua franca in Zambia where the Bemba form the largest ethnic group. The Lamba language is closely related and some people consider it a dialect of Bemba.

In addition to its classical and literary form, Malay had various regional dialects established after the rise of the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra, Indonesia. Also, Malay spread through interethnic contact and trade across the Malay archipelago as far as the Philippines. That contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay or low Malay and in Malay Melayu Pasar. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, influenced by contact among Malay, Hokkien, Portuguese, and Dutch traders.

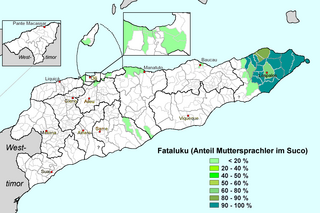

Fataluku is a non-Austronesian language spoken by approximately 37,000 people of Fataluku ethnicity in the eastern areas of East Timor, especially around Lospalos. It is a member of the Timor-Alor-Pantar language family, which includes languages spoken both in East Timor and nearby regions of Indonesia. Fataluku's closest relative is Oirata, spoken on Kisar island, in the Moluccas of Indonesia. Fataluku is given the status of a national language under the constitution. Speakers of Fataluku normally have a command of Tetum and/or Indonesian.

Tshangla is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Bodish branch closely related to the Tibetic languages and much of its vocabulary derives from Classical Tibetan. Tshangla is primarily spoken in Eastern Bhutan and acts as a lingua franca in the country particularly among Sharchop/Tshangla communities; it is also spoken in Arunachal Pradesh, India, and Tibet. Tshangla is the principal pre-Tibetan (pre-Dzongkha) language of Bhutan.

The Central Solomon languages are the four Papuan languages spoken in the state of the Solomon Islands.

Kazukuru is an extinct language that was once spoken in New Georgia, Solomon Islands. The Dororo and Guliguli languages were transcriptional variants, dialects, or closely related. The speakers of Kazukuru gradually merged with the Roviana people from the sixteenth century onward and adopted Roviana as their language. Kazukuru was last recorded in the early twentieth century when its speakers were in the last stages of language shift. Today, Kazukuru is the name of a clan in the Roviana people group.

The ꞌAreꞌare language is spoken by the ꞌAreꞌare people of the southern part of Malaita island, as well as nearby South Malaita Island and the eastern shore of Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands archipelago. It is spoken by about 18,000 people, making it the second-largest Oceanic language in the Solomons after the Kwara'ae. The literacy rate for ꞌAreꞌare is somewhere between 30% and 60% for first language speakers, and 25%–50% for second language learners. There are also translated Bible portions into the language from 1957 to 2008. ꞌAreꞌare is just one of seventy-one languages spoken in the Solomon Islands. It is estimated that at least seven dialects of ꞌAreꞌare exist. Some of the known dialects are Are, Aiaisii, Woo, Iꞌiaa, Tarapaina, Mareho and Marau; however, the written resources on the difference between dialects are rare; with no technical written standard. There are only few resources on the vocabulary of the ꞌAreꞌare language. A written standard has yet to be established, the only official document on the language being the ꞌAreꞌare dictionary written by Peter Geerts, which however does not explain pronunciation, sound systems or the grammar of the language.

Hoava is an Oceanic language spoken by 1000–1500 people on New Georgia Island, Solomon Islands. Speakers of Hoava are multilingual and usually also speak Roviana, Marovo, SI Pijin, English.

Roviana is a member of the North West Solomonic branch of Oceanic languages. It is spoken around Roviana and Vonavona lagoons at the north central New Georgia in the Solomon Islands. It has 10,000 first-language speakers and an additional 16,000 people mostly over 30 years old speak it as a second language. In the past, Roviana was widely used as a trade language and further used as a lingua franca especially for church purposes in the Western Province but now it is being replaced by the Solomon Islands Pijin. Few published studies on Roviana language include: Ray (1926), Waterhouse (1949) and Todd (1978) contain the syntax of Roviana language. Corston-Oliver discuss about the ergativity in Roviana. Todd (2000) and Ross (1988) discuss the clause structure in Roviana. Schuelke (2020) discusses grammatical relations and syntactic ergativity in Roviana.

Ughele is an Oceanic language spoken by about 1200 people on Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

The Lau language is a Malayo-Polynesian group language spoken on northeast Malaita, one of the six large islands that together form the chain of the Solomon Islands. It is located in Oceania, northwest of Vanuatu and east of Papua New Guinea. In 1999 it had about 16,937 first-language speakers, with many second-language speakers through Malaitan communities in the Solomon Islands, especially in Honiara.

Yao is a Bantu language in Africa with approximately two million speakers in Malawi, and half a million each in Tanzania and Mozambique. There are also some speakers in Zambia. In Malawi, the main dialect is Mangochi, mostly spoken around Lake Malawi. In Mozambique, the main dialects are Makale and Massaninga. The language has also gone by several other names in English, including chiYao or ciYao, Achawa, Adsawa, Adsoa, Ajawa, Ayawa, Ayo, Ayao, Djao, Haiao, Hiao, Hyao, Jao, Veiao, and waJao.

The Touo language, also known as Baniata (Mbaniata) or Lokuru, is spoken over the southern part of Rendova Island, located in the Western Province of the Solomon Islands.

Cipu (Cicipu), or Western Acipa, is a Kainji language spoken by about 20,000 people in northwest Nigeria. The people call themselves Acipu, and are called Acipawa in Hausa.

The family of Northwest Solomonic languages is a branch of the Oceanic languages. It includes the Austronesian languages of Bougainville and Buka in Papua New Guinea, and of Choiseul, New Georgia, and Santa Isabel in Solomon Islands.

There are between sixty and seventy languages spoken in the Solomon Islands archipelago. The lingua franca is Pidgin, and the official language is English.

Pijin is a language spoken in the Solomon Islands. It is closely related to Tok Pisin of Papua New Guinea and Bislama of Vanuatu; these might be considered dialects of a single language. It is also related to Torres Strait Creole of Torres Strait, though more distantly.

Mortlockese, also known as Mortlock or Nomoi, is a language that belongs to the Chuukic group of Micronesian languages in the Federated States of Micronesia spoken primarily in the Mortlock Islands. It is nearly intelligible with Satawalese, with an 18 percent intelligibility and an 82 percent lexical similarity, and Puluwatese, with a 75 percent intelligibility and an 83 percent lexical similarity. The language today has become mutually intelligible with Chuukese, though marked with a distinct Mortlockese accent. Linguistic patterns show that Mortlockese is converging with Chuukese since Mortlockese now has an 80 to 85 percent lexical similarity.

References

- ↑ Nduke at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ "Duke, Nduke in Solomon Islands". Joshua Project. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Duke". Ethnologue languages of the world. SIL. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Scales, Ian (2003). The Social Forest: landowners, development conflict and the State in Solomon Islands. PhD Thesis, Australian National University.

- ↑ Palmer, Bill. "New Georgia". An annotated bibliography of Northwest Solomonic materials. University of Surrey. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- ↑ Scales, Ian (1998). Indexing in Nduke (Solomon Islands) (Seminar paper). Canberra: Department of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

- ↑ Hocart, Arthur M. (1908). Nduke vocabulary (TS). TS held at Turnbull Library, Auckland.

- ↑ Tryon, Darrell T.; Hackman, Bryan D. (1983). Solomon Islands languages: an internal classification. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- ↑ "Language: Nduke". Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database. University of Auckland.