A pandemic is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic diseases with a stable number of infected individuals such as recurrences of seasonal influenza are generally excluded as they occur simultaneously in large regions of the globe rather than being spread worldwide.

An epidemic is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of hosts in a given population within a short period of time. For example, in meningococcal infections, an attack rate in excess of 15 cases per 100,000 people for two consecutive weeks is considered an epidemic.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the syndrome caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak. In the 2010s, Chinese scientists traced the virus through the intermediary of Asian palm civets to cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in Xiyang Yi Ethnic Township, Yunnan.

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the common cold, while more lethal varieties can cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19, which is causing the ongoing pandemic. In cows and pigs they cause diarrhea, while in mice they cause hepatitis and encephalomyelitis.

In epidemiology, an infection is said to be endemic in a specific population or populated place when that infection is constantly present, or maintained at a baseline level, without extra infections being brought into the group as a result of travel or similar means. The term describes the distribution (spread) of an infectious disease among a group of people or within a populated area. An endemic disease always has a steady, predictable number of people getting sick, but that number can be high (hyperendemic) or low (hypoendemic), and the disease can be severe or mild. Also, a disease that is usually endemic can become epidemic.

Human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63) is a species of coronavirus, specifically a Setracovirus from among the Alphacoronavirus genus. It was identified in late 2004 in patients in the Netherlands by Lia van der Hoek and Krzysztof Pyrc using a novel virus discovery method VIDISCA. Later on the discovery was confirmed by the researchers from the Rotterdam, the Netherlands The virus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus which enters its host cell by binding to ACE2. Infection with the virus has been confirmed worldwide, and has an association with many common symptoms and diseases. Associated diseases include mild to moderate upper respiratory tract infections, severe lower respiratory tract infection, croup and bronchiolitis.

An emergent virus is a virus that is either newly appeared, notably increasing in incidence/geographic range or has the potential to increase in the near future. Emergent viruses are a leading cause of emerging infectious diseases and raise public health challenges globally, given their potential to cause outbreaks of disease which can lead to epidemics and pandemics. As well as causing disease, emergent viruses can also have severe economic implications. Recent examples include the SARS-related coronaviruses, which have caused the 2002-2004 outbreak of SARS (SARS-CoV-1) and the 2019–21 pandemic of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2). Other examples include the human immunodeficiency virus which causes HIV/AIDS; the viruses responsible for Ebola; the H5N1 influenza virus responsible for avian flu; and H1N1/09, which caused the 2009 swine flu pandemic. Viral emergence in humans is often a consequence of zoonosis, which involves a cross-species jump of a viral disease into humans from other animals. As zoonotic viruses exist in animal reservoirs, they are much more difficult to eradicate and can therefore establish persistent infections in human populations.

A breakthrough infection is a case of illness in which a vaccinated individual becomes infected with the illness, because the vaccine has failed to provide complete immunity against the pathogen. Breakthrough infections have been identified in individuals immunized against a variety of diseases including mumps, varicella (Chickenpox), influenza, and COVID-19. The characteristics of the breakthrough infection are dependent on the virus itself. Often, infection of the vaccinated individual results in milder symptoms and shorter duration than if the infection were contracted naturally.

Immunization during pregnancy is the administration of a vaccine to a pregnant individual. This may be done either to protect the individual from disease or to induce an antibody response, such that the antibodies cross the placenta and provide passive immunity to the infant after birth. In many countries, including the US, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand, vaccination against influenza, COVID-19 and whooping cough is routinely offered during pregnancy.

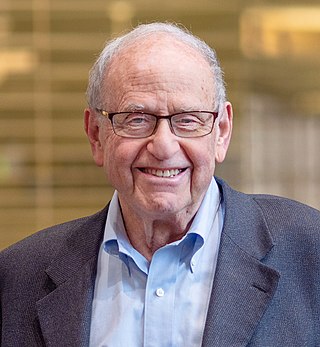

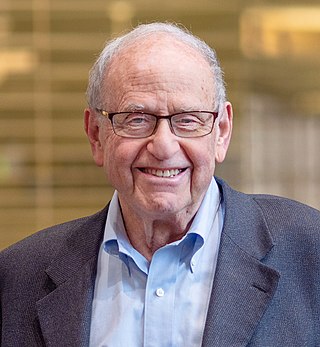

Walter Ian Lipkin is the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of Neurology and Pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also director of the Center for Infection and Immunity, an academic laboratory for microbe hunting in acute and chronic diseases. Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus, SARS and COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is a global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identified in an outbreak in the Chinese city of Wuhan in December 2019. Attempts to contain it there failed, allowing the virus to spread to other areas of Asia and later worldwide in 2020. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) on 30 January 2020. The WHO ended its PHEIC declaration on 5 May 2023. As of 8 November 2023, the pandemic had caused 771,678,854 cases and 6,977,010 confirmed deaths, ranking it fifth in the deadliest epidemics and pandemics in history.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the provisional name 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), and has also been called human coronavirus 2019. First identified in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China, the World Health Organization designated the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern from January 30, 2020, to May 5, 2023. SARS‑CoV‑2 is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus that is contagious in humans.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2. The first known case was identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. The disease quickly spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

A COVID‑19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19).

Arnold Monto is an American physician and epidemiologist. At the University of Michigan School of Public Health, Monto is the Thomas Francis, Jr. Collegiate Professor Emeritus of Public Health, professor emeritus of both epidemiology and global public health, and co-director of the Michigan Center for Respiratory Virus Research & Response. His research focuses on the occurrence, prevention, and treatment of viral respiratory infections in industrialized and developing countries' populations.

Susan R. Weiss is an American microbiologist who is a Professor of Microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. She holds vice chair positions for the Department of Microbiology and for Faculty Development. Her research considers the biology of coronaviruses, including SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2. As of March 2020, Weiss serves as Co-Director of the University of Pennsylvania/Penn Medicine Center for Research on Coronavirus and Other Emerging Pathogens.

Allison Joan McGeer is a Canadian infectious disease specialist in the Sinai Health System, and a professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto. She also appointed at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and a Senior Clinician Scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and is a partner of the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. McGeer has led investigations into the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Toronto and worked alongside Donald Low. During the COVID-19 pandemic, McGeer has studied how SARS-CoV-2 survives in the air and has served on several provincial committees advising aspects of the Government of Ontario's pandemic response.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had many impacts on global health beyond those caused by the COVID-19 disease itself. It has led to a reduction in hospital visits for other reasons. There have been 38 per cent fewer hospital visits for heart attack symptoms in the United States and 40 per cent fewer in Spain. The head of cardiology at the University of Arizona said, "My worry is some of these people are dying at home because they're too scared to go to the hospital." There is also concern that people with strokes and appendicitis are not seeking timely treatment. Shortages of medical supplies have impacted people with various conditions.

Viral interference, also known as superinfection resistance, is the inhibition of viral reproduction caused by previous exposure of cells to another virus. The exact mechanism for viral interference is unknown. Factors that have been implicated are the generation of interferons by infected cells, and the occupation or down-modulation of cellular receptors.

Part of managing an infectious disease outbreak is trying to delay and decrease the epidemic peak, known as flattening the epidemic curve. This decreases the risk of health services being overwhelmed and provides more time for vaccines and treatments to be developed. Non-pharmaceutical interventions that may manage the outbreak include personal preventive measures such as hand hygiene, wearing face masks, and self-quarantine; community measures aimed at physical distancing such as closing schools and cancelling mass gathering events; community engagement to encourage acceptance and participation in such interventions; as well as environmental measures such surface cleaning. It has also been suggested that improving ventilation and managing exposure duration can reduce transmission.