The foreign relations of Afghanistan are in a transitional phase since the 2021 fall of Kabul to the Taliban and the collapse of the internationally recognized Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. No country has recognised the new Taliban-run government, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Although some countries have engaged in informal diplomatic contact with the Islamic Emirate, formal relations remain limited to representatives of the Islamic Republic.

Mohammad Daoud Khan was an Afghan military officer and politician who served as prime minister of Afghanistan from 1953 to 1963 and, as leader of the 1973 Afghan coup d'état which overthrew the monarchy, served as the first president of Afghanistan from 1973 until he himself was deposed in a coup and killed in the Saur Revolution.

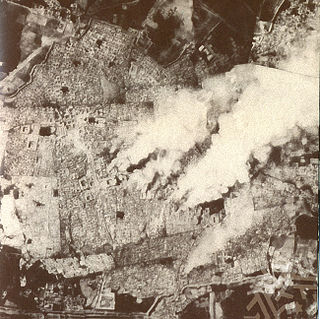

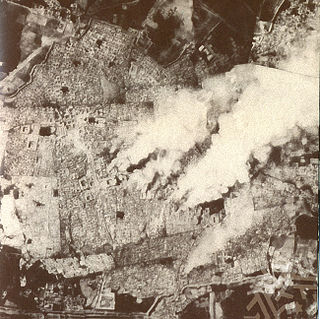

The Soviet–Afghan War took place in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from December 1979 to February 1989. Marking the beginning of the protracted Afghan conflict, it saw the Soviet Union and the Afghan military fight against the rebelling Afghan mujahideen. While they were backed by various countries and organizations, the majority of the mujahideen's support came from Pakistan, the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Iran, and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, in addition to a large influx of foreign fighters known as the Afghan Arabs. American and British involvement on the side of the mujahideen escalated the Cold War, ending a short period of relaxed Soviet Union–United States relations. Combat took place throughout the 1980s, mostly in the Afghan countryside, as most of the country's cities remained under Soviet control. The conflict resulted in the deaths of one to three million Afghans, while millions more fled from the country as refugees; most externally displaced Afghans sought refuge in Pakistan and in Iran. Between 6.5 and 11.5% of Afghanistan's erstwhile population of 13.5 million people is estimated to have been killed over the course of the Soviet–Afghan War. The decade-long confrontation between the mujahideen and the Soviet and Afghan militaries inflicted grave destruction throughout Afghanistan and has also been cited by scholars as a significant factor that contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991; it is for this reason that the conflict is sometimes referred to as "the Soviet Union's Vietnam" in retrospective analyses.

The Great Game was a rivalry between the 19th-century British and Russian empires over influence in Central Asia, primarily in Afghanistan, Persia, and Tibet. The two colonial empires used military interventions and diplomatic negotiations to acquire and redefine territories in Central and South Asia. Russia conquered Turkestan, and Britain expanded and set the borders of British India. By the early 20th century, a line of independent states, tribes, and monarchies from the shore of the Caspian Sea to the Eastern Himalayas were made into protectorates and territories of the two empires.

Afghanistan is a mountainous landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Some of the invaders in the history of Afghanistan include the Maurya Empire, the ancient Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great, the Rashidun Caliphate, the Mongol Empire led by Genghis Khan, the Ghaznavid Empire of Turkic Mahmud of Ghazni, the Ghurid Dynasty of Muhammad of Ghor the Timurid Empire of Timur, the Mughal Empire, various Persian Empires, the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and most recently the United States with a number of allies in response to the September 11 attacks. A reduced number of NATO troops remained in the country in support of the government. Just prior to the American withdrawal in 2021, the Taliban regained control of the capital Kabul and most of the country. They changed Afghanistan's official name to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

The Basmachi movement was an uprising against Imperial Russian and Soviet rule in Central Asia by rebel groups inspired by Islamic beliefs.

After the Russian Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks took over parts of the collapsing Russian Empire in 1918, they faced enormous odds against the German Empire and eventually negotiated terms to pull out of World War I. They then went to war against the White movement, pro-independence movements, rebellious peasants, former supporters, anarchists and foreign interventionists in the bitter civil war. They set up the Soviet Union in 1922 with Vladimir Lenin in charge. At first, it was treated as an unrecognized pariah state because of its repudiating of tsarist debts and threats to destroy capitalism at home and around the world. By 1922, Moscow had repudiated the goal of world revolution, and sought diplomatic recognition and friendly trade relations with the capitalist world, starting with Britain and Germany. Finally, in 1933, the United States gave recognition. Trade and technical help from Germany and the United States arrived in the late 1920s. After Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin, became leader. He transformed the country in the 1930s into an industrial and military power. It strongly opposed Nazi Germany until August 1939, when it came to peaceful terms with Berlin in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. Moscow and Berlin by agreement invaded and partitioned Poland and the Baltic States. The non-aggression pact was broken in June 1941 when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. The Soviet forces nearly collapsed as the Germans reached the outskirts of Leningrad and Moscow. However, the Soviet Union proved strong enough to defeat Nazi Germany, with help from its key World War II allies, Britain and the United States. The Soviet army occupied most of Eastern Europe and increasingly controlled the governments.

Relations between Afghanistan and the United States began in 1921 under the leaderships of King Amanullah Khan and President Warren G. Harding, respectively. The first contact between the two nations occurred further back in the 1830s when the first recorded person from the United States explored Afghanistan. The United States government foreign aid program provided about $500 million in aid for economic development; the aid ended before the 1978 Saur Revolution. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 was a turning point in the Cold War, when the United States started to financially support the Afghan resistance. The country, under both the Carter and Reagan administrations committed $3 billion in financial and diplomatic support and along with Pakistan also rendering critical support to the anti-Soviet Mujahideen forces. Beginning in 1980, the United States began admitting thousands of Afghan refugees for resettlement, and provided money and weapons to the Mujahideen through Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). The USSR withdrew its troops in 1989.

Russia–United Kingdom relations, also Anglo-Russian relations, are the bilateral relations between the Russian Federation and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Formal ties between the nations started in 1553. Russia and Britain became allies against Napoleon in the early-19th century. They were enemies in the Crimean War of the 1850s, and rivals in the Great Game for control of central Asia in the latter half of the 19th century. They allied again in World Wars I and II, although the Russian Revolution of 1917 strained relations. The two countries again became enemies during the Cold War (1947–1989). Russia's business tycoons developed strong ties with London financial institutions in the 1990s after the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. Due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations became very tense after the United Kingdom imposed sanctions against Russia. It was subsequently added to Russia's list of "unfriendly countries".

Relations between Afghanistan and Germany date back to the late 19th century and have historically been strong. 100 years of "friendship" were celebrated in 2016, with the Afghan President calling it a "historical relationship".

Iraq–Russia relations are the bilateral relations between Iraq and Russia and, prior to Russia's independence, between Iraq and the Soviet Union. The current Iraqi Ambassador to Russia is Haidar Mansour Hadi Al-Athari who has been serving his second post in Moscow since June 2024.

Afghanistan and Pakistan are neighboring countries. In August 1947, the partition of British India led to the emergence of Pakistan along Afghanistan's eastern frontier; Afghanistan was the sole country to vote against Pakistan's admission into the United Nations following the latter's independence. Territorial disputes along the widely known "Durand Line" and conflicting claims prevented the normalization of bilateral ties between the countries throughout the mid-20th century. Afghan territorial claims over Pashtun-majority areas that are in Pakistan were coupled with discontent over the permanency of the Durand Line which has long been considered the international border by every nation other than Afghanistan, and for which Afghanistan demanded a renegotiation, with the aim of having it shifted eastward to the Indus River. During the Taliban insurgency, the Taliban has received substantial financial and logistical backing from Pakistan, which remains a significant source of support. Nonetheless, Pakistan's support for the Taliban is not without risks, as it involves playing a precarious and delicate game. Further Afghanistan–Pakistan tensions have arisen concerning a variety of issues, including the Afghan conflict and Afghan refugees in Pakistan and water-sharing rights but most of all the Taliban government in Afghanistan providing sanctuary and safe havens to Pakistani Taliban terrorists to attack Pakistani territory. Border tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan have escalated to an unprecedented degree following recent instances of violence along the border. The Durand Line witnesses frequent occurrences of suicide bombings, airstrikes, or street battles on an almost daily basis. The Taliban-led Afghan government has also accused Pakistan of undermining relations between Afghanistan and China and creating discord between the neighbouring countries.

Diplomatic relations between Afghanistan and China were established in the 18th century, when Afghanistan was ruled by Ahmad Shah Durrani and China by Qianlong. But trade relations between these nations date back to at least the Han dynasty with the profitable Silk Road. Presently, China has an embassy in Kabul and Afghanistan has one in Beijing. The two countries share a 92 km (57 mi) border.

Diplomatic relations between the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and Japan were officially established in 1931, although early contacts date back to 1907 when the Afghan general Ayub Khan, who defeated the British in the 1880 Battle of Maiwand, visited Japan.

Pakistan's principal intelligence and covert action agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), has historically conducted a number of clandestine operations in its western neighbor, Afghanistan. ISI's covert support to militant jihadist insurgent groups in Afghanistan, the Pashtun-dominated former Federally Administered Tribal Areas, and Kashmir has earned it a wide reputation as the primary progenitor of many active South Asian jihadist groups.

Pakistan and the Soviet Union had complex and tense relations. During the Cold War (1947–1991), Pakistan was a part of Western Bloc of the First World and a close ally of the United States.

Bilateral relations of Afghanistan and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland span a long and eventful history, dating back to the United Kingdom's Company rule in India, the British-Russian rivalry in Central Asia, and the border between modern Afghanistan and British India. There has been an Afghan embassy in London since 1922 though there was no accredited Afghan ambassador from 1981 to 2001.

The Red Army intervention in Afghanistan in 1929 also known as the First Soviet Intervention in Afghanistan of 1929 was a special operation aimed at supporting the ousted king of Afghanistan, Amanullah Khan, against the Saqqawists and Basmachi.

Shir Muhammad-bek Gazi, also known as Mahmud-Bek also known under the nickname Korshirmat was a prominent figure of the Basmachi Movement in exile since 1923, the first head of the Turkestan Union during the Great Patriotic War with the support of the Abwehr to restore the insurrectionary movement in Turkestan.

The Cold War in Asia was a major dimension of the worldwide Cold War that shaped diplomacy and warfare from the mid-1940s to 1991. The main countries involved were the United States, the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, South Korea, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, Cambodia, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Thailand, Laos, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Taiwan. In the late 1950s, divisions between China and the Soviet Union deepened, culminating in the Sino-Soviet split, and the two then vied for control of communist movements across the world, especially in Asia.