Cnidaria is a phylum under kingdom Animalia containing over 11,000 species of aquatic animals found both in freshwater and marine environments, including jellyfish, hydroids, sea anemone, corals and some of the smallest marine parasites. Their distinguishing feature is the cnidocytes, specialized cells with ejectable flagella used mainly for envenomation and capturing prey. Their bodies consist of mesoglea, a non-living jelly-like substance, sandwiched between two layers of epithelium that are mostly one cell thick.

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.

Anthozoa is a class of marine invertebrates which includes the sea anemones, stony corals and soft corals. Adult anthozoans are almost all attached to the seabed, while their larvae can disperse as part of the plankton. The basic unit of the adult is the polyp; this consists of a cylindrical column topped by a disc with a central mouth surrounded by tentacles. Sea anemones are mostly solitary, but the majority of corals are colonial, being formed by the budding of new polyps from an original, founding individual. Colonies are strengthened by calcium carbonate and other materials and take various massive, plate-like, bushy or leafy forms.

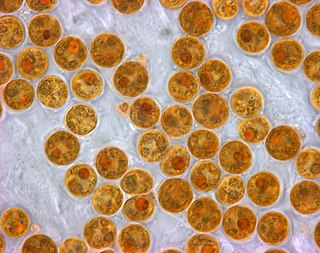

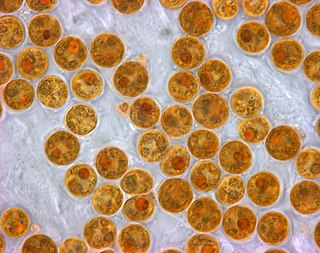

Zooxanthellae is a colloquial term for single-celled dinoflagellates that are able to live in symbiosis with diverse marine invertebrates including demosponges, corals, jellyfish, and nudibranchs. Most known zooxanthellae are in the genus Symbiodinium, but some are known from the genus Amphidinium, and other taxa, as yet unidentified, may have similar endosymbiont affinities. The true Zooxanthella K.brandt is a mutualist of the radiolarian Collozoum inerme and systematically placed in Peridiniales. Another group of unicellular eukaryotes that partake in similar endosymbiotic relationships in both marine and freshwater habitats are green algae zoochlorellae.

Zoochlorella is a nomen rejiciendum for a genus of green algae assigned to Chlorella. The term zoochlorella is sometimes used to refer to any green algae that lives symbiotically within the body of a freshwater or marine invertebrate or protozoan. Zoochlorellae and zooxanthellae may both be found in the Pacific coast sea anemones Anthopleura elegantissima and Anthopleura xanthogrammica.

Symbiodinium is a genus of dinoflagellates that encompasses the largest and most prevalent group of endosymbiotic dinoflagellates known. These unicellular microalgae commonly reside in the endoderm of tropical cnidarians such as corals, sea anemones, and jellyfish, where the products of their photosynthetic processing are exchanged in the host for inorganic molecules. They are also harbored by various species of demosponges, flatworms, mollusks such as the giant clams, foraminifera (soritids), and some ciliates. Generally, these dinoflagellates enter the host cell through phagocytosis, persist as intracellular symbionts, reproduce, and disperse to the environment. The exception is in most mollusks, where these symbionts are intercellular. Cnidarians that are associated with Symbiodinium occur mostly in warm oligotrophic (nutrient-poor), marine environments where they are often the dominant constituents of benthic communities. These dinoflagellates are therefore among the most abundant eukaryotic microbes found in coral reef ecosystems.

Aiptasia is a genus of a symbiotic cnidarian belonging to the class Anthozoa. Aiptasia is a widely distributed genus of temperate and tropical sea anemones of benthic lifestyle typically found living on mangrove roots and hard substrates. These anemones, as well as many other cnidarian species, often contain symbiotic dinoflagellate unicellular algae of the genus Symbiodinium living inside nutritive cells. The symbionts provide food mainly in the form of lipids and sugars produced from photosynthesis to the host while the hosts provides inorganic nutrients and a constant and protective environment to the algae. Species of Aiptasia are relatively weedy anemones able to withstand a relatively wide range of salinities and other water quality conditions. In the case of A. pallida and A. pulchella, their hardiness coupled with their ability to reproduce very quickly and out-compete other species in culture gives these anemones the status of pest from the perspective of coral reef aquarium hobbyists. These very characteristics make them easy to grow in the laboratory and thus they are extensively used as model organisms for scientific study. In this respect, Aiptasia have contributed a significant amount of knowledge regarding cnidarian biology, especially human understanding of cnidarian-algal symbioses, a biological phenomenon crucial to the survival of corals and coral reef ecosystems. The dependence of coral reefs on the health of the symbiosis is dramatically illustrated by the devastating effects experienced by corals due to the loss of algal symbionts in response to environmental stress, a phenomenon known as coral bleaching.

The snakelocks anemone is a sea anemone found in the eastern Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. The latter population is however sometimes considered a separate species, the Mediterranean snakelocks anemone.

The starburst anemone or sunburst anemone is a species of sea anemone in the family Actiniidae. The sunburst anemone was formerly considered the solitary form of the common aggregating anemone, but was identified as a separate species in 2000.

Sea anemones are a group of predatory marine invertebrates constituting the order Actiniaria. Because of their colourful appearance, they are named after the Anemone, a terrestrial flowering plant. Sea anemones are classified in the phylum Cnidaria, class Anthozoa, subclass Hexacorallia. As cnidarians, sea anemones are related to corals, jellyfish, tube-dwelling anemones, and Hydra. Unlike jellyfish, sea anemones do not have a medusa stage in their life cycle.

Cassiopea andromeda is one of many cnidarian species called the upside-down jellyfish. It usually lives in intertidal sand or mudflats, shallow lagoons, and around mangroves. This jellyfish, often mistaken for a sea anemone, usually keeps its mouth facing upward. Its yellow-brown bell, which has white or pale streaks and spots, pulsates to run water through its arms for respiration and to gather food.

Anthopleura xanthogrammica, or the giant green anemone, is a species of intertidal sea anemone of the family Actiniidae.

Stichodactyla helianthus, commonly known as sun anemone, is a sea anemone of the family Stichodactylidae. Helianthus stems from the Greek words ἡλιος, and ἀνθος, meaning flower. S. helianthus is a large, green, sessile, carpet-like sea anemone, from the Caribbean. It lives in shallow areas with mild to strong currents.

A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comprise more than half of all microscopic plankton. There are two types of eukaryotic mixotrophs: those with their own chloroplasts, and those with endosymbionts—and those that acquire them through kleptoplasty or through symbiotic associations with prey or enslavement of their organelles.

Actinia bermudensis, the red, maroon or stinging anemone, is a species of sea anemone in the family Actiniidae.

Anthopleura ballii, commonly known as the red speckled anemone, is a species of sea anemone in the family Actiniidae. It is found in shallow water in the northeastern Atlantic Ocean.

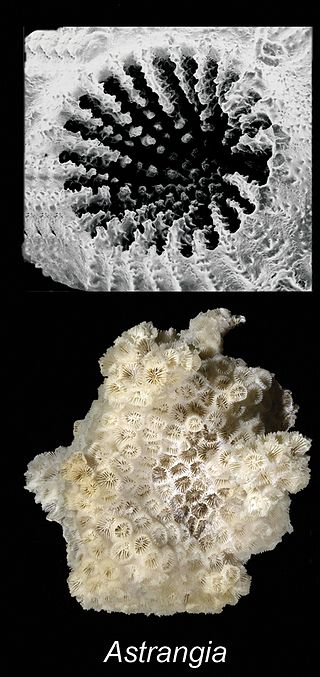

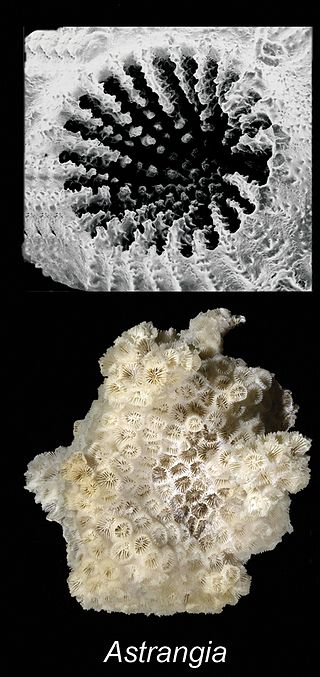

Astrangia poculata, the northern star coral or northern cup coral, is a species of non-reefbuilding stony coral in the family Rhizangiidae. It is native to shallow water in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. It is also found on the western coast of Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists this coral as being of "least concern". Astrangia poculata is an emerging model organism for corals because it harbors a facultative photosymbiosis, is a calcifying coral, and has a large geographic range. Research on this emerging model system is showcased annually by the Astrangia Research Working Group, collaboratively hosted by Roger Williams University, Boston University, and Southern Connecticut State University

Isozoanthus sulcatus is a species of zoanthid in the family Parazoanthidae.

The Enthemonae is a suborder of sea anemones in the order Actiniaria. It comprises those sea anemones with typical arrangement of mesenteries for actiniarians.

Aeolidia loui is a species of sea slugs, an aeolid nudibranch, a marine gastropod mollusc in the family Aeolidiidae. It has been regarded as the same species as the NE Atlantic Aeolidia papillosa but is now known to be a distinct species. Common names include shaggy mouse nudibranch, and shag-rug nudibranch.