Environmental finance is a field within finance that employs market-based environmental policy instruments to improve the ecological impact of investment strategies. The primary objective of environmental finance is to regress the negative impacts of climate change through pricing and trading schemes. The field of environmental finance was established in response to the poor management of economic crises by government bodies globally. Environmental finance aims to reallocate a businesses resources to improve the sustainability of investments whilst also retaining profit margins.

The Clear Skies Act of 2003 was a proposed federal law of the United States. The official title as introduced is "a bill to amend the Clean Air Act to reduce air pollution through expansion of cap-and-trade programs, to provide an alternative regulatory classification for units subject to the cap and trade program, and for other purposes."

The American Coalition for Clean Coal Electricity is a U.S. non-profit advocacy group representing major American coal producers, utility companies and railroads. The organization seeks to influence public opinion and legislation in favor of coal-generated electricity in the United States, placing emphasis on the development and deployment of clean coal technologies.

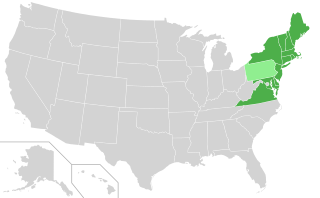

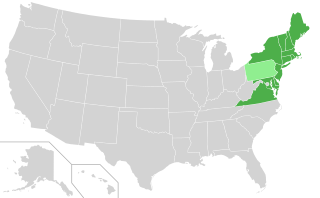

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI, pronounced "Reggie") is the first mandatory market-based program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by the United States. RGGI is a cooperative effort among the states of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia to cap and reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the power sector. RGGI compliance obligations apply to fossil-fueled power plants 25 megawatts (MW) and larger within the 11-state region. Pennsylvania's participation in the RGGI cooperative was ruled unconstitutional on November 1, 2023, although that decision has been appealed. North Carolina's entrance into RGGI has been blocked by the enactment of the state's fiscal year 2023–25 budget.

The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, or Assembly Bill (AB) 32, is a California state law that fights global warming by establishing a comprehensive program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all sources throughout the state. AB32 was co-authored by Assemblymember Fran Pavley and Speaker of the California Assembly Fabian Nunez and signed into law by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger on September 27, 2006.

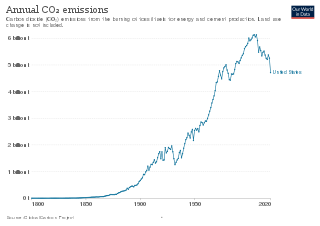

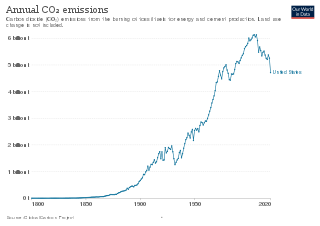

The United States produced 5.2 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2020, the second largest in the world after greenhouse gas emissions by China and among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person. In 2019 China is estimated to have emitted 27% of world GHG, followed by the United States with 11%, then India with 6.6%. In total the United States has emitted a quarter of world GHG, more than any other country. Annual emissions are over 15 tons per person and, amongst the top eight emitters, is the highest country by greenhouse gas emissions per person.

The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme was a cap-and-trade emissions trading scheme for anthropogenic greenhouse gases proposed by the Rudd government, as part of its climate change policy, which had been due to commence in Australia in 2010. It marked a major change in the energy policy of Australia. The policy began to be formulated in April 2007, when the federal Labor Party was in Opposition and the six Labor-controlled states commissioned an independent review on energy policy, the Garnaut Climate Change Review, which published a number of reports. After Labor won the 2007 federal election and formed government, it published a Green Paper on climate change for discussion and comment. The Federal Treasury then modelled some of the financial and economic impacts of the proposed CPRS scheme.

The Global Warming Pollution Reduction Act of 2007 (S. 309) was a bill proposed to amend the 1963 Clean Air Act, a bill that aimed to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). U.S. Senator, Bernie Sanders (I-VT), introduced the resolution in the 110th United States Congress on January 16, 2007. The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works but was not enacted into law.

The America's Climate Security Act of 2007 was a global warming bill that was considered by the United States Senate to reduce the amount of greenhouse gases emitted in the United States. Also known as the Lieberman–Warner bill, bill number S. 2191, the legislation was introduced by Sens. Joseph Lieberman (I-CT) and John Warner (R-VA) on October 18, 2007. The bill was approved by the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works in December 2007, and was debated in the Senate during the week of June 2. The bill would create a national cap-and-trade scheme for greenhouse gas emissions, in which polluters would mostly be allocated right-to-emit credits based on how much greenhouse gas they currently emit. The cap would get tighter over time, until by 2050, emissions would be reduced to 63% below 2005 levels. Several environmental groups expressed their encouragement at the progress in legislation on the global warming issue while at the same time expressing disappointment that the bill did not reduce emissions enough. On June 6, 2008, the bill was killed by Senate Republicans over worries that it would damage the economy.

Carbon emission trading (also called carbon market, emission trading scheme (ETS) or cap and trade) is a type of emissions trading scheme designed for carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs). A form of carbon pricing, its purpose is to limit climate change by creating a market with limited allowances for emissions. Carbon emissions trading is a common method that countries use to attempt to meet their pledges under the Paris Agreement, with schemes operational in China, the European Union, and other countries.

The environmental policy of the United States is a federal governmental action to regulate activities that have an environmental impact in the United States. The goal of environmental policy is to protect the environment for future generations while interfering as little as possible with the efficiency of commerce or the liberty of the people and to limit inequity in who is burdened with environmental costs. Framing of environmental issues often influences how policies are developed, especially when economic concerns or national security are used to either justify or contest actions. As his first official act bringing in the 1970s, President Richard Nixon signed the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) into law on New Year's Day, 1970. Also in the same year, America began celebrating Earth Day, which has been called "the big bang of U.S. environmental politics, launching the country on a sweeping social learning curve about ecological management never before experienced or attempted in any other nation." NEPA established a comprehensive US national environmental policy and created the requirement to prepare an environmental impact statement for "major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the environment." Author and consultant Charles H. Eccleston has called NEPA the world's "environmental Magna Carta".

New Energy for America was a plan led by President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden beginning in 2008 to invest in renewable energy sources, reduce reliance on foreign oil, address global warming issues, and create jobs for Americans. The main objective of the New Energy for America plan was to implement clean energy sources in the United States to switch from nonrenewable resources to renewable resources. The plan led by the Obama Administration aimed to implement short-term solutions to provide immediate relief from pain at the pump, and mid- to- long-term solutions to provide a New Energy for America plan. The goals of the clean energy plan hoped to: invest in renewable technologies that will boost domestic manufacturing and increase homegrown energy, invest in training for workers of clean technologies, strengthen the middle class, and help the economy.

A low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) is an emissions trading rule designed to reduce the average carbon intensity of transportation fuels in a given jurisdiction, as compared to conventional petroleum fuels, such as gasoline and diesel. The most common methods for reducing transportation carbon emissions are supplying electricity to electric vehicles, supplying hydrogen fuel to fuel cell vehicles and blending biofuels, such as ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel, and renewable natural gas into fossil fuels. The main purpose of a low-carbon fuel standard is to decrease carbon dioxide emissions associated with vehicles powered by various types of internal combustion engines while also considering the entire life cycle, in order to reduce the carbon footprint of transportation.

The climate change policy of the United States has major impacts on global climate change and global climate change mitigation. This is because the United States is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gasses in the world after China, and is among the countries with the highest greenhouse gas emissions per person in the world. Cumulatively, the United States has emitted over a trillion metric tons of greenhouse gases, more than any country in the world.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began regulating greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Clean Air Act from mobile and stationary sources of air pollution for the first time on January 2, 2011. Standards for mobile sources have been established pursuant to Section 202 of the CAA, and GHGs from stationary sources are currently controlled under the authority of Part C of Title I of the Act. The basis for regulations was upheld in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in June 2012.

Energy Tax Prevention Act, also known as H.R. 910, was a 2011 bill in the United States House of Representatives to prohibit the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from regulating greenhouse gases to address climate change. On April 7, 2011, the bill passed the House by a vote of 255 to 172. The bill died in January 2013 with the ending of the Congressional session.

The Clean Energy Act 2011 was an Act of the Australian Parliament, the main Act in a package of legislation that established an Australian emissions trading scheme (ETS), to be preceded by a three-year period of fixed carbon pricing in Australia designed to reduce carbon dioxide emissions as part of efforts to combat global warming.

The Electricity Security and Affordability Act is a bill that would repeal a pending rule published by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on January 8, 2014. The proposed rule would establish uniform national limits on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from new electricity-generating facilities that use coal or natural gas. The rule also sets new standards of performance for those power plants, including the requirement to install carbon capture and sequestration technology.

The Clean Power Plan was an Obama administration policy aimed at combating climate change that was first proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in June 2014. The final version of the plan was unveiled by President Barack Obama on August 3, 2015. Each state was assigned a target for reducing carbon emissions within its borders, which could be accomplished how the states saw fit, but with the possibility of the EPA stepping in if a state refused to submit a plan. If every state met its target, the plan was projected to reduce carbon emissions from electricity generation by 32 percent relative to 2005 levels by 2030, and would have reduced other harmful air pollution as well.

As the most populous state in the United States, California's climate policies influence both global climate change and federal climate policy. In line with the views of climate scientists, the state of California has progressively passed emission-reduction legislation.