Weaknesses

Weaknesses of doing an ACH matrix include:

- The process to create an ACH is time-consuming.

- The ACH matrix can be problematic when analyzing a complex project.

- It can be cumbersome for an analyst to manage a large database with multiple pieces of evidence.

- Evidence also presents a problem if it is unreliable.

- The evidence used in the matrix is static and therefore it can be a snapshot in time.

Especially in intelligence, both governmental and business, analysts must always be aware that the opponent(s) is intelligent and may be generating information intended to deceive. [3] [4] Since deception often is the result of a cognitive trap, Elsaesser and Stech use state-based hierarchical plan recognition (see abductive reasoning) to generate causal explanations of observations. The resulting hypotheses are converted to a dynamic Bayesian network and value of information analysis is employed to isolate assumptions implicit in the evaluation of paths in, or conclusions of, particular hypotheses. As evidence in the form of observations of states or assumptions is observed, they can become the subject of separate validation. Should an assumption or necessary state be negated, hypotheses depending on it are rejected. This is a form of root cause analysis.

According to social constructivist critics, ACH also fails to stress sufficiently (or to address as a method) the problematic nature of the initial formation of the hypotheses used to create its grid. There is considerable evidence, for example, that in addition to any bureaucratic, psychological, or political biases that may affect hypothesis generation, there are also factors of culture and identity at work. These socially constructed factors may restrict or pre-screen which hypotheses end up being considered, and then reinforce confirmation bias in those selected. [5]

Philosopher and argumentation theorist Tim van Gelder has made the following criticisms: [6]

- ACH demands that the analyst makes too many discrete judgments, a great many of which contribute little if anything to discerning the best hypothesis

- ACH misconceives the nature of the relationship between items of evidence and hypotheses by supposing that items of evidence are, on their own, consistent or inconsistent with hypotheses.

- ACH treats the hypothesis set as "flat", i.e. a mere list, and so is unable to relate evidence to hypotheses at the appropriate levels of abstraction

- ACH cannot represent subordinate argumentation, i.e. the argumentation bearing up on a piece of evidence.

- ACH activities at realistic scales leave analysts disoriented or confused.

Van Gelder proposed hypothesis mapping (similar to argument mapping) as an alternative to ACH. [7] [8]

Structured analysis of competing hypotheses

The structured analysis of competing hypotheses offers analysts an improvement over the limitations of the original ACH.[ discuss ] [9] The SACH maximizes the possible hypotheses by allowing the analyst to split one hypothesis into two complex ones.

For example, two tested hypotheses could be that Iraq has WMD or Iraq does not have WMD. If the evidence showed that it is more likely there are WMDs in Iraq then two new hypotheses could be formulated: WMD are in Baghdad or WMD are in Mosul. Or perhaps, the analyst may need to know what type of WMD Iraq has; the new hypotheses could be that Iraq has biological WMD, Iraq has chemical WMD and Iraq has nuclear WMD. By giving the ACH structure, the analyst is able to give a nuanced estimate. [10]

One method, by Valtorta and colleagues uses probabilistic methods, adds Bayesian analysis to ACH. [11] A generalization of this concept to a distributed community of analysts lead to the development of CACHE (the Collaborative ACH Environment), [12] which introduced the concept of a Bayes (or Bayesian) community. The work by Akram and Wang applies paradigms from graph theory. [13]

Other work focuses less on probabilistic methods and more on cognitive and visualization extensions to ACH, as discussed by Madsen and Hicks. [14] DECIDE, discussed under automation is visualization-oriented. [15]

Work by Pope and Jøsang uses subjective logic, a formal mathematical methodology that explicitly deals with uncertainty. [16] This methodology forms the basis of the Sheba technology that is used in Veriluma's intelligence assessment software.

A statistical hypothesis test is a method of statistical inference used to decide whether the data at hand sufficiently support a particular hypothesis. Hypothesis testing allows us to make probabilistic statements about population parameters.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one's prior beliefs or values. People display this bias when they select information that supports their views, ignoring contrary information, or when they interpret ambiguous evidence as supporting their existing attitudes. The effect is strongest for desired outcomes, for emotionally charged issues, and for deeply entrenched beliefs. Confirmation bias is insuperable for most people, but they can manage it, for example, by education and training in critical thinking skills.

Abductive reasoning is a form of logical inference that seeks the simplest and most likely conclusion from a set of observations. It was formulated and advanced by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce beginning in the last third of the 19th century.

Scientific evidence is evidence that serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis, although scientists also use evidence in other ways, such as when applying theories to practical problems. Such evidence is expected to be empirical evidence and interpretable in accordance with the scientific method. Standards for scientific evidence vary according to the field of inquiry, but the strength of scientific evidence is generally based on the results of statistical analysis and the strength of scientific controls.

The Office of Special Plans (OSP), which existed from September 2002 to June 2003, was a Pentagon unit created by Paul Wolfowitz and Douglas Feith, and headed by Feith, as charged by then–United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, to supply senior George W. Bush administration officials with raw intelligence pertaining to Iraq. A similar unit, called the Iranian Directorate, was created several years later, in 2006, to deal with intelligence on Iran.

The Senate Report on Iraqi WMD Intelligence was the report by the United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence concerning the U.S. intelligence community's assessments of Iraq during the time leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The report, which was released on July 9, 2004, identified numerous failures in the intelligence-gathering and -analysis process. The report found that these failures led to the creation of inaccurate materials that misled both government policy makers and the American public.

The Iraq War began with the US-led 2003 invasion of Iraq. The Government of Canada did not at any time formally declare war against Iraq, and the level and nature of this participation, which changed over time, was controversial. Canada's intelligence services repeatedly assessed that Iraq did not have an active WMD program.

Data analysis is the process of inspecting, cleansing, transforming, and modeling data with the goal of discovering useful information, informing conclusions, and supporting decision-making. Data analysis has multiple facets and approaches, encompassing diverse techniques under a variety of names, and is used in different business, science, and social science domains. In today's business world, data analysis plays a role in making decisions more scientific and helping businesses operate more effectively.

Intelligence analysis is the application of individual and collective cognitive methods to weigh data and test hypotheses within a secret socio-cultural context. The descriptions are drawn from what may only be available in the form of deliberately deceptive information; the analyst must correlate the similarities among deceptions and extract a common truth. Although its practice is found in its purest form inside national intelligence agencies, its methods are also applicable in fields such as business intelligence or competitive intelligence.

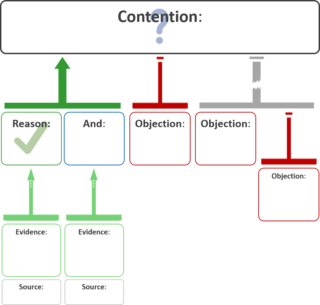

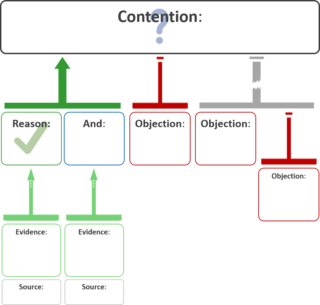

An argument map or argument diagram is a visual representation of the structure of an argument. An argument map typically includes all the key components of the argument, traditionally called the conclusion and the premises, also called contention and reasons. Argument maps can also show co-premises, objections, counterarguments, rebuttals, and lemmas. There are different styles of argument map but they are often functionally equivalent and represent an argument's individual claims and the relationships between them.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to thought (thinking):

Words of estimative probability are terms used by intelligence analysts in the production of analytic reports to convey the likelihood of a future event occurring. A well-chosen WEP gives a decision maker a clear and unambiguous estimate upon which to base a decision. Ineffective WEPs are vague or misleading about the likelihood of an event. An ineffective WEP places the decision maker in the role of the analyst, increasing the likelihood of poor or snap decision making. Some intelligence and policy failures appear to be related to the imprecise use of estimative words.

The target-centric approach to intelligence is a method of intelligence analysis that Robert M. Clark introduced in his book "Intelligence Analysis: A Target-Centric Approach" in 2003 to offer an alternative methodology to the traditional intelligence cycle. Its goal is to redefine the intelligence process in such a way that all of the parts of the intelligence cycle come together as a network. It is a collaborative process where collectors, analysts and customers are integral, and information does not always flow linearly.

Visual analytics is an outgrowth of the fields of information visualization and scientific visualization that focuses on analytical reasoning facilitated by interactive visual interfaces.

Richards "Dick" J. Heuer, Jr. was a CIA veteran of 45 years and most known for his work on analysis of competing hypotheses and his book, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. The former provides a methodology for overcoming intelligence biases while the latter outlines how mental models and natural biases impede clear thinking and analysis. Throughout his career, he worked in collection operations, counterintelligence, intelligence analysis and personnel security. In 2010 he co-authored a book with Randolph (Randy) H. Pherson titled Structured Analytic Techniques for Intelligence Analysis.

The Structured Geospatial Analytic Method (SGAM) is both as an analytic method and pedagogy for the Geospatial Intelligence professional. This model was derived from and incorporates aspects of both Pirolli and Card’s sensemaking process and Richards Heuer’s Analysis of Competing Hypotheses model. This is a simplified view of the geospatial analytic process within the larger intelligence cycle.

In network theory, link analysis is a data-analysis technique used to evaluate relationships between nodes. Relationships may be identified among various types of nodes (100k), including organizations, people and transactions. Link analysis has been used for investigation of criminal activity, computer security analysis, search engine optimization, market research, medical research, and art.

Cross-impact analysis is a methodology developed by Theodore Gordon and Olaf Helmer in 1966 to help determine how relationships between events would impact resulting events and reduce uncertainty in the future. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) became interested in the methodology in the late 1960s and early 1970s as an analytic technique for predicting how different factors and variables would impact future decisions. In the mid-1970s, futurists began to use the methodology in larger numbers as a means to predict the probability of specific events and determine how related events impacted one another. By 2006, cross-impact analysis matured into a number of related methodologies with uses for businesses and communities as well as futurists and intelligence analysts.

Forensic statistics is the application of probability models and statistical techniques to scientific evidence, such as DNA evidence, and the law. In contrast to "everyday" statistics, to not engender bias or unduly draw conclusions, forensic statisticians report likelihoods as likelihood ratios (LR). This ratio of probabilities is then used by juries or judges to draw inferences or conclusions and decide legal matters. Jurors and judges rely on the strength of a DNA match, given by statistics, to make conclusions and determine guilt or innocence in legal matters.

Indicator analysis is a structured analytic technique used in intelligence analysis. It uses historical data to expose trends and identify upcoming major shifts in a subject area, helping the analyst provide evidence-based forecasts with reduced cognitive bias.