Filariasis is a filarial infection caused by parasitic nematodes (roundworms) spread by different vectors. They are included in the list of neglected tropical diseases.

Blood worm or bloodworm is an ambiguous term and can refer to:

Toxocariasis is an illness of humans caused by the dog roundworm and, less frequently, the cat roundworm. These are the most common intestinal roundworms of dogs, coyotes, wolves and foxes and domestic cats, respectively. Humans are among the many "accidental" or paratenic hosts of these roundworms.

Gnathostomiasis, also known as larva migrans profundus, is the human infection caused by the nematode Gnathostoma spinigerum and/or Gnathostoma hispidum, which infects vertebrates.

Strongyloidiasis is a human parasitic disease caused by the nematode called Strongyloides stercoralis, or sometimes the closely related S. fülleborni. These helminths belong to a group of nematodes called roundworms. These intestinal worms can cause a number of symptoms in people, principally skin symptoms, abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss, but also many other specific and vague symptoms in disseminated disease, and severe life-threatening conditions through hyperinfection. In some people, particularly those who require corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medication, Strongyloides can cause a hyperinfection syndrome that can lead to death if untreated. The diagnosis is made by blood and stool tests. The medication ivermectin is widely used to treat strongyloidiasis.

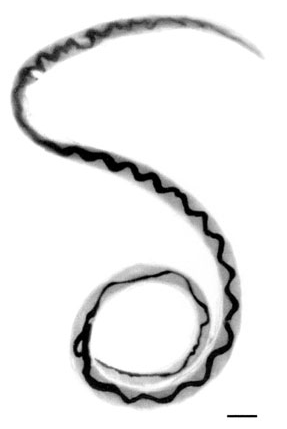

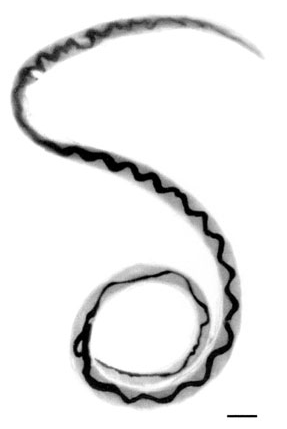

Anisakis is a genus of parasitic nematodes that have life cycles involving fish and marine mammals. They are infective to humans and cause anisakiasis. People who produce immunoglobulin E in response to this parasite may subsequently have an allergic reaction, including anaphylaxis, after eating fish infected with Anisakis species.

Eosinophilic pneumonia is a disease in which an eosinophil, a type of white blood cell, accumulates in the lungs. These cells cause disruption of the normal air spaces (alveoli) where oxygen is extracted from the atmosphere. Several different kinds of eosinophilic pneumonia exist and can occur in any age group. The most common symptoms include cough, fever, difficulty breathing, and sweating at night. Eosinophilic pneumonia is diagnosed by a combination of characteristic symptoms, findings on a physical examination by a health provider, and the results of blood tests and X-rays. Prognosis is excellent once most eosinophilic pneumonia is recognized and treatment with corticosteroids is begun.

Lymphatic filariasis is a human disease caused by parasitic worms known as filarial worms. Usually acquired in childhood, it is a leading cause of permanent disability worldwide, impacting over a hundred million people and manifesting itself in a variety of severe clinical pathologies While most cases have no symptoms, some people develop a syndrome called elephantiasis, which is marked by severe swelling in the arms, legs, breasts, or genitals. The skin may become thicker as well, and the condition may become painful. Affected people are often unable to work and are often shunned or rejected by others because of their disfigurement and disability.

Mammomonogamus is a genus of parasitic nematodes of the family Syngamidae that parasitise the respiratory tracts of cattle, sheep, goats, deer, cats, orangutans, and elephants. The nematodes can also infect humans and cause the disease called mammomonogamiasis. Several known species fall under the genus Mammomonogamus, but the most common species found to infest humans is M. laryngeus. Infection in humans is very rare, with only about 100 reported cases worldwide, and is assumed to be largely accidental. Cases have been reported from the Caribbean, China, Korea, Thailand, and Philippines.

Diphyllobothriasis is the infection caused by tapeworms of the genus Diphyllobothrium.

Necatoriasis is the condition of infection by Necator hookworms, such as Necator americanus. This hookworm infection is a type of helminthiasis (infection) which is a type of neglected tropical disease.

Toxocara canis is a worldwide-distributed helminth parasite that primarily infects dogs and other canids, but can also infect other animals including humans. The name is derived from the Greek word toxon 'bow, quiver' and the Latin word caro 'flesh'. T. canis live in the small intestine of the definitive host. This parasite is very common in puppies and somewhat less common in adult dogs. In adult dogs, infection is usually asymptomatic but may be characterized by diarrhea. By contrast, untreated infection with Toxocara canis can be fatal in puppies, causing diarrhea, vomiting, pneumonia, enlarged abdomen, flatulence, poor growth rate, and other complications.

Angiostrongylus cantonensis is a nematode (roundworm) parasite that causes angiostrongyliasis, an infection that is the most common cause of eosinophilic meningitis in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Basin. The nematode commonly resides in the pulmonary arteries of rats, giving it the common name rat lungworm. Snails and slugs are the primary intermediate hosts, where larvae develop until they are infectious.

Angiostrongylus costaricensis is a species of parasitic nematode and is the causative agent of abdominal angiostrongyliasis in humans. It occurs in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Thelidomus aspera is a species of air-breathing land snail, a terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusc in the family Pleurodontidae. It is endemic to Jamaica.

Angiostrongylus vasorum, also known as French heartworm, is a species of parasitic nematode in the family Metastrongylidae. It causes the disease canine angiostrongylosis in dogs. It is not zoonotic, that is, it cannot be transmitted to humans.

Baylisascaris procyonis, also known by the common name raccoon roundworm, is a roundworm nematode, found ubiquitously in raccoons, the definitive hosts. It is named after H. A. Baylis, who studied them in the 1920s–30s, and Greek askaris. Baylisascaris larvae in paratenic hosts can migrate, causing larva migrans. Baylisascariasis as the zoonotic infection of humans is rare, though extremely dangerous due to the ability of the parasite's larvae to migrate into brain tissue and cause damage. Concern for human infection has been increasing over the years due to the urbanization of rural areas, resulting in the increase in proximity and potential human interaction with raccoons.

Gnathostoma hispidum is a nematode (roundworm) that infects many vertebrate animals including humans. Infection of Gnathostoma hispidum, like many species of Gnathostoma causes the disease gnathostomiasis due to the migration of immature worms in the tissues.

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus is a species of nematode from the family Angiostrongylidae.

Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases (GPDs) are a group of infectious diseases that require a gastropod species to serve as an intermediate host for a parasitic organism that can infect humans upon ingesting the parasite or coming into contact with contaminated water sources. These diseases can cause a range of symptoms, from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening conditions, with them being prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly in developing regions. Preventive measures such as proper sanitation and hygiene practices, avoiding contact with infected gastropods and cooking or boiling food properly can help to reduce the risk of these diseases.