Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes or trematodes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive host, where the flukes sexually reproduce, is a vertebrate. Infection by trematodes can cause disease in all five traditional vertebrate classes: mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish.

Clonorchis sinensis, the Chinese liver fluke, is a liver fluke belonging to the class Trematoda, phylum Platyhelminthes. It infects fish-eating mammals, including humans. In humans, it infects the common bile duct and gall bladder, feeding on bile. It was discovered by British physician James McConnell at the Medical College Hospital in Calcutta (Kolkata) in 1874. The first description was given by Thomas Spencer Cobbold, who named it Distoma sinense. The fluke passes its lifecycle in three different hosts, namely freshwater snail as first intermediate hosts, freshwater fish as second intermediate host, and mammals as definitive hosts.

Praziquantel (PZQ), sold under the brandname Biltricide among others, is a medication used to treat a number of types of parasitic worm infections in mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish. In humans specifically, it is used to treat schistosomiasis, clonorchiasis, opisthorchiasis, tapeworm infections, cysticercosis, echinococcosis, paragonimiasis, fasciolopsiasis, and fasciolosis. It should not be used for worm infections of the eye. It is taken by mouth.

Clonorchiasis is an infectious disease caused by the Chinese liver fluke and two related species. Clonorchiasis is a known risk factor for the development of cholangiocarcinoma, a neoplasm of the biliary system.

Fasciolopsiasis results from an infection by the trematode Fasciolopsis buski, the largest intestinal fluke of humans, growing up to 7.5 cm (3.0 in) long.

Metagonimiasis is a disease caused by an intestinal trematode, most commonly Metagonimus yokagawai, but sometimes by M. takashii or M. miyatai. The metagonimiasis-causing flukes are one of two minute flukes called the heterophyids. Metagonimiasis was described by Katsurasa in 1911–1913 when he first observed eggs of M. yokagawai in feces. M. takahashii was described later first by Suzuki in 1930 and then M. miyatai was described in 1984 by Saito.

Tribendimidine is a broad-spectrum anthelmintic agent developed in China, at the National Institute of Parasitic Diseases in Shanghai. It is a derivative of amidantel.

Opisthorchis viverrini, common name Southeast Asian liver fluke, is a food-borne trematode parasite from the family Opisthorchiidae that infects the bile duct. People are infected after eating raw or undercooked fish. Infection with the parasite is called opisthorchiasis. O. viverrini infection also increases the risk of cholangiocarcinoma, a cancer of the bile ducts.

Echinostoma is a genus of trematodes (flukes), which can infect both humans and other animals. These intestinal flukes have a three-host life cycle with snails or other aquatic organisms as intermediate hosts, and a variety of animals, including humans, as their definitive hosts.

Opisthorchis felineus, the Siberian liver fluke or cat liver fluke, is a trematode parasite that infects the liver in mammals. It was first discovered in 1884 in a cat's liver by Sebastiano Rivolta of Italy. In 1891, Russian parasitologist, Konstantin Nikolaevich Vinogradov (1847–1906) found it in a human, and named the parasite a "Siberian liver fluke". In the 1930s, helminthologist Hans Vogel of Hamburg published an article describing the life cycle of Opisthorchis felineus. Felineus infections may also involve the pancreatic ducts. Diagnosis of Opisthorchis infection is based on microscopic identification of parasite eggs in stool specimens. Safe and effective medication is available to treat Opisthorchis infections. Adequately freezing or cooking fish will kill the parasite.

Liver fluke is a collective name of a polyphyletic group of parasitic trematodes under the phylum Platyhelminthes. They are principally parasites of the liver of various mammals, including humans. Capable of moving along the blood circulation, they can occur also in bile ducts, gallbladder, and liver parenchyma. In these organs, they produce pathological lesions leading to parasitic diseases. They have complex life cycles requiring two or three different hosts, with free-living larval stages in water.

Heterophyes heterophyes, or the intestinal fish fluke, was discovered by Theodor Maximaillian Bilharz in 1851. This parasite was found during an autopsy of an Egyptian mummy. H. heterophyes is found in the Middle East, West Europe and Africa. They use different species to complete their complex lifestyle. Humans and other mammals are the definitive host, first intermediate host are snails, and second intermediate are fish. Mammals that come in contact with the parasite are dogs, humans, and cats. Snails that are affected by this parasite are the Cerithideopsilla conica. Fish that come in contact with this parasite are Mugil cephalus, Tilapia milotica, Aphanius fasciatus, and Acanthgobius sp. Humans and mammals will come in contact with this parasite by the consumption of contaminated or raw fish. This parasite is one of the smallest endoparasite to infect humans. It can cause intestinal infection called heterophyiasis.

Bithynia siamensis is a species of a freshwater snail with a gill and an operculum, an aquatic prosobranch gastropod mollusk in the family Bithyniidae.

Koi is a "salad" dish of the Lao people living in modern-day Laos and Isan, Thailand, consisting of raw meat denatured by acidity, usually from lime juice. Common varieties include koi kung, with shrimp as the main ingredient, and koi paa /koi pla, which consists of minced or finely chopped raw fish in spicy salad dressing.

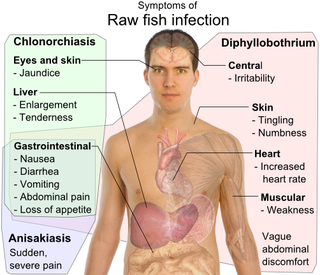

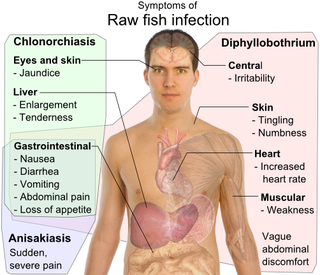

Trematodiasis is a group of parasitic infections due different species of flukes, the trematodes. Symptoms can range from mild to severe depending on the species, number and location of trematodes in the infected organism. Symptoms depend on type of trematode present, and include chest and abdominal pain, high temperature, digestion issues, cough and shortness of breath, diarrhoea and change in appetite.

Banchob Sripa is a Thai scientist who is professor and head of the Tropical Disease Research Laboratory (TDRL) at Khon Kaen University in Khon Kaen, Thailand. He is also the head of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Research and Control of Opisthorchiasis, an infectious parasitic disease caused by the Southeast Asian liver fluke, which is endemic in northeastern Thailand and other portions of the Mekong River basin. He is also coordinator for the Asian Neglected Tropical Disease Network. He has a doctorate in tropical health from the University of Queensland, Australia. He received the Outstanding Scientist Award from the Foundation for the Promotion of Science and Technology in 2013.

The Integrated Opisthorchiasis Control Program, commonly known as the "Lawa Project", located in Khon Kaen Province, Thailand, is an effort to reduce chronic infection by the Southeast Asian liver fluke among the native peoples of Isan, the northeast region of Thailand. The project operates under the aegis of the Tropical Disease Research Laboratory, Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University. It is directed by Banchob Sripa. Its aim is to eliminate the practice of consuming raw or undercooked fish, the major cause of liver fluke infection and bile duct cancer in the region. The project is unique in that it follows the principles of EcoHealth, a One Health approach to improving human and animal health. The project has been the subject of newspaper and TV reports by BBC, The New York Times, and The Guardian.

Carcinogenic parasites are parasitic organisms that depend on other organisms for their survival, and cause cancer in such hosts. Three species of flukes (trematodes) are medically-proven carcinogenic parasites, namely the urinary blood fluke, the Southeast Asian liver fluke and the Chinese liver fluke. S. haematobium is prevalent in Africa and the Middle East, and is the leading cause of bladder cancer. O. viverrini and C. sinensis are both found in eastern and southeastern Asia, and are responsible for cholangiocarcinoma. The International Agency for Research on Cancer declared them in 2009 as a Group 1 biological carcinogens in humans.

Paul J Brindley is an Australian parasitologist, microbiologist, and helminthologist. He is professor of Microbiology, Immunology, and Tropical Medicine at the George Washington University.

Gastropod-borne parasitic diseases (GPDs) are a group of infectious diseases that require a gastropod species to serve as an intermediate host for a parasitic organism that can infect humans upon ingesting the parasite or coming into contact with contaminated water sources. These diseases can cause a range of symptoms, from mild discomfort to severe, life-threatening conditions, with them being prevalent in many parts of the world, particularly in developing regions. Preventive measures such as proper sanitation and hygiene practices, avoiding contact with infected gastropods and cooking or boiling food properly can help to reduce the risk of these diseases.