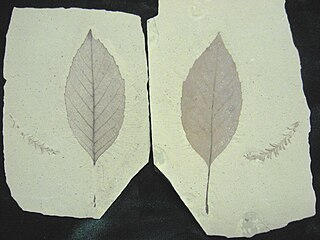

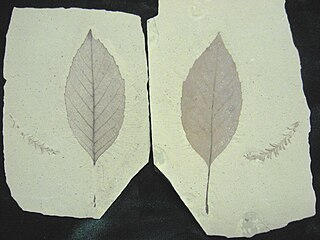

Tilia johnsoni is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Malvaceae that, as a member of the genus Tilia, is related to modern lindens. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state, United States and a similar aged formation in British Columbia, Canada.

Rhus malloryi is an extinct species of flowering plant in the sumac family Anacardiaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state, United States. The species was first described from a series of isolated fossil leaves in shale. R. malloryi is one of four sumac species to be described from the Klondike Mountain Formation, and forms a hybrid complex with the other three species.

Langeria is an extinct genus of flowering plants in the family Platanaceae containing the solitary species Langeria magnifica. Langeria is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state, United States and similar aged formations in British Columbia, Canada.

Tsukada is an extinct genus of flowering plant in the family Nyssaceae related to the modern "dove-tree", Davidia involucrata, containing the single species Tsukada davidiifolia. The genus is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state, United States and a similar aged formation in British Columbia, Canada.

Rhus boothillensis is an extinct species of flowering plant in the sumac family Anacardiaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington State, United States. The species was first described from fossil leaves found in the Klondike Mountain Formation. Rhus boothillensis likely hybridized with the other Klondike Mountain formation sumac species Rhus garwellii, Rhus malloryi, and Rhus republicensis.

Rhus garwellii is an extinct species of flowering plant in the sumac family Anacardiaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington State, United States. The species was first described from fossil leaves found in the Klondike Mountain Formation. R. garwellii likely hybridized with the other Klondike Mountain formation sumac species R. boothillensis, R. malloryi, and R. republicensis.

Rhus republicensis is an extinct species of flowering plant in the sumac family, Anacardiaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state in the United States. The species was first described from fossil leaves found in the Klondike Mountain Formation. R. republicensis likely hybridized with the other Klondike Mountain formation sumac species Rhus boothillensis, Rhus garwellii, and Rhus malloryi.

Tetracentron hopkinsii is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Trochodendraceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of northern Washington state, United States and south Central British Columbia. The species was first described from fossil leaves found in the Allenby Formation. T. hopkinsii are possibly the leaves belonging to the extinct trochodendraceous fruits Pentacentron sternhartae.

Comptonia columbiana is an extinct species of sweet fern in the flowering plant family Myricaceae. The species is known from fossil leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of central to southern British Columbia, Canada, plus northern Washington state, United States, and, tentatively, the late Eocene of Southern Idaho and Earliest Oligocene of Oregon, United States.

Acer spitzi is an extinct maple species in the family Sapindaceae described from a single fossil samara. The species is solely known from the Early Eocene sediments exposed in northeast Washington state, United States. It is the only species belonging to the extinct section Spitza.

Carpinus perryae is an extinct species of hornbeam known from fossil fruits found in the Klondike Mountain Formation deposits of northern Washington state, dated to the early Eocene Ypresian stage. Based on described features, C. perryae is the oldest definite species in the genus Carpinus.

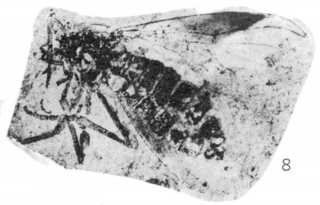

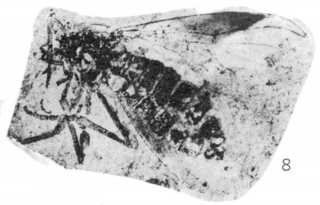

Klondikia is an extinct hymenopteran genus in the ant family Formicidae with a single described species Klondikia whiteae. The species is solely known from the Early Eocene sediments exposed in northeast Washington state, United States. The genus is currently not placed into any ant subfamily, being treated as incertae sedis.

Equisetum similkamense is an extinct horsetail species in the family Equisetaceae described from a group of whole plant fossils including rhizomes, stems, and leaves. The species is known from Ypresian sediments exposed in British Columbia, Canada. It is one of several extinct species placed in the living genus Equisetum.

Pteronepelys, sometimes known as the winged stranger, is an extinct genus of flowering plant of uncertain affinities, which contains the one species, Pteronepelys wehrii. It is known from isolated fossil seeds found in middle Eocene sediments exposed in north central Oregon and Ypresian-age fossils found in Washington, US.

Fagus langevinii is an extinct species of beech in the family Fagaceae. The species is known from fossil fruits, nuts, pollen, and leaves found in the early Eocene deposits of South central British Columbia, and northern Washington state, United States.

Plecia canadensis is an extinct species of Plecia in the fly family Bibionidae. The species is solely known from Early Eocene sediments exposed in central southern British Columbia. The species is one of twenty bibionid species described from the Eocene Okanagan Highlands paleofauna.

Ulmus chuchuanus is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Ulmaceae related to the modern elms. The species is known from fossil leaves and fruits found in early Eocene sites of northern Washington state, United States and central British Columbia, Canada.

Promastax is a genus of "monkey grasshoppers" belonging to the extinct monotypic family Promastacidae and containing the single species Promastax archaicus. The species is dated to the Early Eocenes Ypresian stage and has only been found at the type locality in east central British Columbia.

Alnus parvifolia is an extinct species of flowering plant in the family Betulaceae related to the modern birches. The species is known from fossil leaves and possible fruits found in early Eocene sites of northern Washington state, United States, and central British Columbia, Canada.

Republicopteron is an extinct orthopteran genus in the katydid-like family Palaeorehniidae with a single described species Republicopteron douseae. The species is solely known from the Early Eocene sediments exposed in northeast Washington state, United States. The family is currently not placed into any orthoptera superfamily, being treated as incertae sedis, and thus the relationship between Republicopteron and the other palaeorehniids with the larger cricket/katydid superfamilies is uncertain. Additionally the possibility that several palaeorehniids may be sister species was left open, an further specimens are needed for resolution of the relationships or synonymies between the genera.