| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

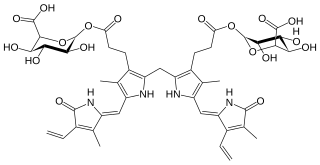

| IUPAC name 3-[12-(2-Carboxyethyl)-3,18-diethenyl-2,7,13,17-tetramethyl-1,19-dioxo-10,19,21,22,23,24-hexahydro-1H-bilin-8-yl]propanoyl β-D-glucopyranosiduronic acid | |

| Systematic IUPAC name [12(2)Z,102S,103R,104S,105S,106S]-34-(2-Carboxyethyl)-14-ethenyl-55-[(Z)-(3-ethenyl-4-methyl-5-oxo-1,5-dihydro-2H-pyrrol-2-ylidene)methyl]-103,104,105-trihydroxy-13,33,54-trimethyl-15,8-dioxo-11,15-dihydro-31H,51H-9-oxa-1(2),3(2,5),5(2,3)-tripyrrola-10(2)-oxanadecaphan-12(2)-ene-106-carboxylic acid | |

| Other names Bilirubin monoglucuronide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C39H44N4O12 | |

| Molar mass | 760.797 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Bilirubin glucuronide is a water-soluble reaction intermediate over the process of conjugation of indirect bilirubin. [1] Bilirubin glucuronide itself belongs to the category of conjugated bilirubin along with bilirubin di-glucuronide. [2] However, only the latter one is primarily excreted into the bile in the normal setting. [2] [3] [4] [5] [1]

Contents

- Clinical significance

- Renal

- Dubin–Johnson syndrome

- Liver failure or hepatitis

- Crigler Najjar disease

- Gilbert's syndrome

- Neonate jaundice

- Hemolytic jaundice

- Brain damage

- Notes

- References

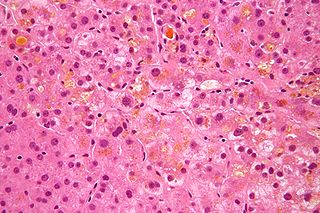

Upon macrophages spot and phagocytize the effete Red Blood Corpuscles containing hemoglobin, [6] unconjugated bilirubin is discharged from macrophages into the blood plasma. [7] [8] Most often, the free and water-insoluble unconjugated bilirubin which has an internal hydrodren[ clarification needed ] bonding [9] will bind to albumin and, to a much lesser extent, high density lipoprotein in order to decrease its hydrophobicity and to limit the probability of unnecessary contact with other tissues [1] [9] and keep bilirubin in the vascular space from traversing to extravascular space including brain, and from ending up increasing glomerular filtration. [9] Nevertheless, there is still a little portion of indirect bilirubins stays free-of-bound. [9] Free unconjugated bilirubin can poison the cerebrum. [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] [15] [16] [17] [18] [19]

Finally, albumin leads the indirect bilirubin to the liver. [1] [9] In the liver sinusoid, albumin disassociates with the indirect bilirubin and returns to the circulation while the hepatocyte transfers the indirect bilirubin to ligandin and glucuronide conjugates the indirect bilirubin in the endoplasmic reticulum by disrupting unconjugated bilirubin's internal hydrogen bonding, which is the thing that makes indirect bilirubin having the property of eternal half-elimination life and insoluble in water, [20] [9] [1] [21] [22] and by attaching two molecules of glucuronic acid to it in a two step process. [23] The reaction is a transfer of two glucuronic acid groups including UDP glucuronic acid sequentially to the propionic acid groups of the bilirubin, primarily catalyzed by UGT1A1. [23] [24] [5] In greater detail about this reaction, a glucuronosyl moiety is conjugated to one of the propionic acid side chains, located on the C8 and C12 carbons of the two central pyrrole rings of bilirubin. [25]

When the first step is completely done, the substrate bilirubin glucuronide (also known as mono-glucuronide [26] ) is born at this stage and is water-soluble and readily excreted in bile. [24] [9] Thereafter, so long as the second step of attachment of the other glucuronic acid to it succeeds (officially called "re-glucuronidated" [26] ), the substrate bilirubin glucuronide will turn into bilirubin di-glucuronide (8,12-diglucuronide [26] ) and be excreted into bile canaliculi by way of C-MOAT [note 1] [27] [28] [29] [30] and MRP2 [5] [31] as normal human bile along with a little amount of unconjugated bilirubin as much as only 1 to 4 percent of total pigments in normal bile. [9] [32] That means up to 96%-99% of bilirubin in the bile are conjugated. [9] [1]

Normally, there is just a little conjugated bilirubin escapes into the general circulation. [1] Nonetheless, in the setting of severe liver disease, a significantly greater number of conjugated bilirubin will leak into circulation and then dissolve into the blood [note 2] and thereby filtered by the kidney, and only a part of the leaked conjugated bilirubin will be re-absorbed in the renal tubules, the remainder will be present in the urine making it dark-colored. [1] [3]